'Brothers in the forest' - the fight to protect an isolated Amazon tribe

- Published

Tomas Chavez Loma was working in a small clearing in the Peruvian Amazon, when he heard footsteps approaching in the forest.

He realised he was surrounded, and froze.

"One was standing, aiming with an arrow," he says. "And somehow he noticed I was here and I started to run."

He had come face to face with the Mashco Piro. For decades, Tomas - who lives in the small village of Nueva Oceania - had been practically a neighbour to these nomadic people, who shun contact with outsiders. However, until very recently, he had rarely seen them.

The Mashco Piro have chosen to be cut off from the world for more than a century. They hunt with long bows and arrows, relying on the Amazonian rainforest for everything they need.

"They started circling and whistling, imitating animals, many different types of birds," Tomas recalls.

"I kept saying: 'Nomole' (brother). Then they gathered, they felt closer, so we headed toward the river and ran."

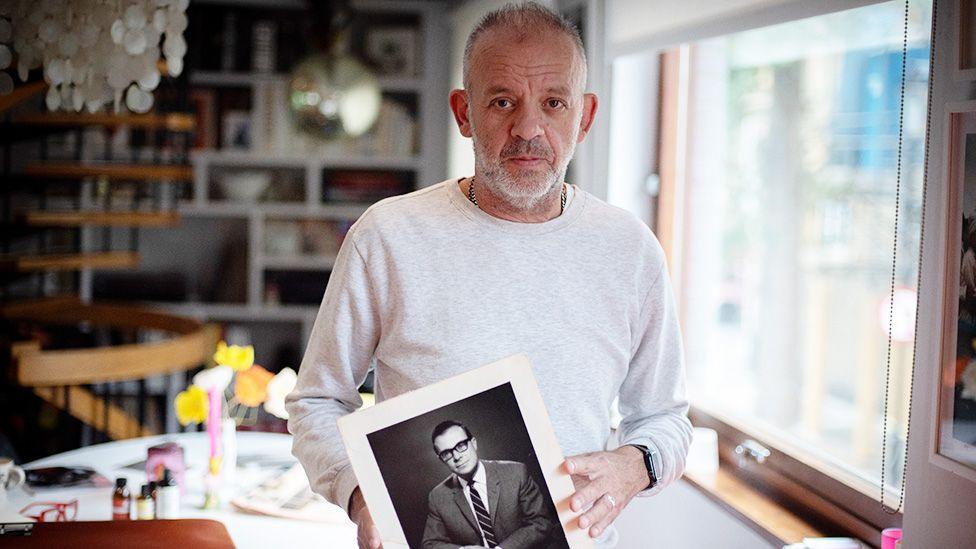

Tomas feels protective towards the Mashco Piro: "Let them live as they live"

A new report by the human rights organisation, Survival International, says there are at least 196 of what it calls "uncontacted groups" left in the world, external. The Mashco Piro is believed to be the largest. The report says half of these groups could be wiped out in the next decade if governments don't do more to protect them.

It claims the biggest risks are from logging, mining or drilling for oil. Uncontacted groups are extremely vulnerable to basic disease - as such, the report says a threat is posed by contact with evangelical missionaries and social media influencers looking for clicks.

Recently, Mashco Piro people have been coming to Nueva Oceania more and more, according to locals.

The village is a fishing community of seven or eight families, sitting high on the banks of the Tauhamanu River in the heart of the Peruvian Amazon, 10 hours from the nearest settlement by boat.

The area is not recognised as a protected reserve for uncontacted groups, and logging companies operate here.

Tomas says that, at times, the noise of logging machinery can be heard day and night, and the Mashco Piro people are seeing their forest disturbed and destroyed.

In Nueva Oceania, people say they are conflicted. They fear the Mashco Piro's arrows but they also have deep respect for their "brothers" who live in the forest and want to protect them.

"Let them live as they live, we can't change their culture. That's why we keep our distance," says Tomas.

Mashco Piro people photographed in Tambopata province in Madre de Dios, Peru in June 2024

The people in Nueva Oceania are worried about the damage to the Mascho Piro's livelihood, the threat of violence and the possibility that loggers might expose the Mashco Piro to diseases they have no immunity to.

While we were in the village, the Mashco Piro made their presence felt again. Letitia Rodriguez Lopez, a young mother with a two-year-old daughter, was in the forest picking fruit when she heard them.

"We heard shouting, cries from people, many of them. As if there were a whole group shouting," she told us.

It was the first time she had encountered the Mashco Piro and she ran. An hour later, her head was still pounding from fear.

"Because there are loggers and companies cutting down the forest they're running away, maybe out of fear and they end up near us," she said. "We don't know how they might react to us. That's what scares me."

In 2022, two loggers were attacked by the Mashco Piro while fishing. One was hit by an arrow to the gut. He survived, but the other man was found dead days later with nine arrow wounds in his body.

Nueva Oceania is a small fishing village in the Peruvian rainforest

The Peruvian government has a policy of non-contact with isolated people, making it illegal to initiate interactions with them.

The policy originated in Brazil after decades of campaigning by indigenous rights groups, who saw that initial contact with isolated people lead to entire groups being wiped out by disease, poverty and malnutrition.

In the 1980s, when the Nahau people in Peru made initial contact with the world outside, 50% of their population died within a matter of years. In the 1990s, the Muruhanua people faced the same fate.

"Isolated indigenous peoples are very vulnerable - epidemiologically, any contact could transmit diseases, and even the simplest ones could wipe them out," says Isrrail Aquise from the Peruvian indigenous rights group, Femanad. "Culturally too, any contact or interference can be very harmful to their life and health as a society."

For the neighbours of uncontacted tribes, the reality of no-contact can be tricky.

As Tomas shows us around the forest clearing where he encountered the Mashco Piro, he stops, whistles through his hands and then waits in silence.

"If they answer, we turn back," he says. All we can hear is the chatter of insects and birds. "They're not here."

Tomas feels the government has left the residents of Nueva Oceania to handle a tense situation by themselves.

He plants food in his garden for the Mashco Piro to take. It is a safety measure he and other villagers have come up with to help their neighbours and protect themselves.

"I wish I knew the words to say, 'Here have these plantains, it's a gift,'" he adds. "'You can take them freely. Don't shoot me.'"

At the control post

Almost 200km south-east on the other side of the dense forest, the situation is very different. There, by the Manu River, the Mashco Piro live in an area that is officially recognised as a forest reserve.

The Peruvian Ministry of Culture and Fenamad run the "Nomole" control post here, staffed by eight agents. It was set up in 2013 when conflict between Mashco Piro and local villages resulted in several killings.

As the head of the control post, Antonio Trigoso Ydalgo's job is to stop that from happening again.

The Mashco Piro appear regularly, sometimes several times a week. They are a different group of people from those near Nueva Oceania, and the agents don't believe they know each other.

Mashco Piro people approach the Nomole control post

"They always come out at the same place. That's where they shout from," Antonio says, pointing across the wide Manu River to a small shingly beach on the other side. They ask for plantain, yucca or sugar cane.

"If we don't answer, they sit there all day waiting," Antonio says. The agents try to avoid that, in case tourists or local boats pass by. So they usually comply. The control post has a small garden they grow food in. When it runs out, they ask a local village for supplies.

If these aren't available, the agents ask the Mashco Piro to come back in a few days' time. It has worked so far, and there has been little conflict recently.

There are about 40 people who Antonio sees regularly - men, women and children from several different families.

They name themselves after animals. The chief is called Kamotolo (Honey Bee). The agents say he is a stern man and never smiles.

Another leader, Tkotko (Vulture) is more of a joker, he laughs a lot and makes fun of the agents. There is a young woman called Yomako (Dragon) who the agents say has a good sense of humour too.

The Mashco Piro don't seem to have much interest in the outside world but are interested in the personal lives of the agents they meet. They ask about their families and where they live.

A monkey-tooth necklace presented as a gift by the Mashco Piro to one of the agents at Nomole

When one agent was pregnant and went on maternity leave, they brought a rattle made from the throat of a howler monkey for the baby to play with.

They are interested in the agents' clothes, especially sports clothes in red or green. "When we approach, we put on old, torn clothes with missing buttons - so they don't take them," Antonio says.

"Before, they wore their own traditional clothing - very beautiful skirts made with threads from insect fibres that they crafted themselves. But now some of them, when tourist boats pass, receive clothes or boots." says Eduardo Pancho Pisarlo, an agent at the control post.

Little is still known about who the Mashco Piro people are

But any time the team ask about life in the forest, the Mashco Piro shut the conversation down.

"Once, I asked how they light their fires," says Antonio. "They told me, 'You have wood, you know.' I insisted, and they said, 'You already have all these things - why do you want to know?'"

If someone doesn't appear for quite a while, the agents will ask where they are. If the Mashco Piro say, "Don't ask", they take it to mean that person has died.

After years of contact, the agents still know little about how the Mashco Piro live or why they remain in the forest.

It is believed they may be descended from indigenous people who fled into the deep jungle in the late 19th Century, escaping rampant exploitation and widespread massacres by so-called "rubber barons".

Experts think the Mashco Piro may be closely related to the Yine, an indigenous people from south-eastern Peru. They speak an antiquated dialect of the same language, which the agents, who are also Yine, have been able to learn.

But the Yine have long been river navigators, farmers and fishermen, while the Mashco Piro seem to have forgotten how to do these things. They may have become nomads and hunter-gatherers to stay safe.

"What I understand now is that they stay in one area for a while, set up a camp, and the whole family gather," says Antonio. "Once they've hunted everything around that place, they move to another site."

The Mashco Piro hunt in the Amazon rainforest using spears and arrows

Isrrail Aquise from Fenamad says more than 100 people have come out in front of the control post at various times.

"They ask for bananas and cassava to diversify their diet, but some families disappear for months or years after that," he says.

"They just say: 'I'm going away for a few moons, then I'll come back.' And they say goodbye."

The Mashco Piro in this area are well protected but the government is building a road which will connect it to an area where illegal mining is widespread.

But it is clear to the agents that the Mashco Piro do not want to join the outside world.

"From my experience here at the post, they don't want to become 'civilised'," Antonio says.

Antonio says he regularly sees about 40 people regularly at the "Nomole" control post

"Maybe the children do, as they grow up and see us wearing clothes, perhaps in 10 or 20 years. But the adults don't. They don't even want us here," he says.

In 2016, a government bill was passed to extend the Mashco Piro's reserve to an area that would include Nueva Oceania. However, this has never been signed into law.

"We need them to be free like us," says Tomas. "We know they lived very peacefully for years, and now their forests are being finished off - destroyed."

Related topics

More weekend picks

- Published18 October

- Published29 June 2024