'It’s not every day you meet another Vietnam orphan'

Andy [left] and Barton [right] say they have formed a lifelong bond

- Published

Andy Yearley and Barton Williams grew up at opposite ends of the world - but when they met, they discovered a shared past.

Both were "rescued" from Saigon orphanages after the US withdrew its troops from Vietnam in the early 1970s.

Thousands of children were rehomed in the United States but Barton grew up in south Australia and Andy ended up on the Scottish island of Lewis.

The pair met by chance in 2021 while Barton was starring in a surfing film set on the island.

They had both grown up as Asian children in a predominantly white communities, with no memory or knowledge of Vietnam.

"It’s not every day you meet another Vietnam orphan," Andy says.

“It's like meeting a twin brother – a blood brother.

"We just clicked straight away."

The bond between the two men has been brought to life on stage at the Edinburgh Fringe in Precious Cargo - a theatre performance telling the stories of the Vietnamese orphans.

The show explores the individual experience of each person but also their shared feelings of displacement.

"Andy has lived almost a repeat life to mine but in Scotland," Barton says in his broad Australian accent.

"He has grown up in a very predominant white middle-class environment.

“He looks full Viet, but he doesn’t sound like a Viet - just like me."

A Fringe show, called Precious Cargo, explores the stories of the Vietnamese orphans

Andy was adopted by Eileen and Iain Yearley after he had been found in the Saigon orphanage by a friend of the family.

According to Andy, the only flight he could be put on was to Orly airport in France.

"My adoptive mum had to travel there - apparently there was no-one with me,” Andy says.

"I was left alone as a baby in the airport.”

He was brought up in the village of Keose, about 12 miles from Stornoway, the main town on Lewis.

He says he wore thick NHS glasses and had long black hair to protect his ears after they were damaged in Vietnam.

"I was one of the only Asian people in the Western Isles, certainly the only Vietnamese," he says.

His parents never mentioned Vietnam, he says.

"They were my parents and I was their child," Andy says.

Andy is just one of 3,300 Vietnamese war orphans taken from Vietnam

By early 1975, it was becoming clear that the war would end as South Vietnam strongholds fell to the communist forces of the Viet Cong.

Hundreds of thousands of refugees fled by air and sea, including westerners and Vietnamese people who had supported the Americans.

The US military had left the country two years prior but a feeling of concern and panic was building among the Western public for the orphaned children left behind.

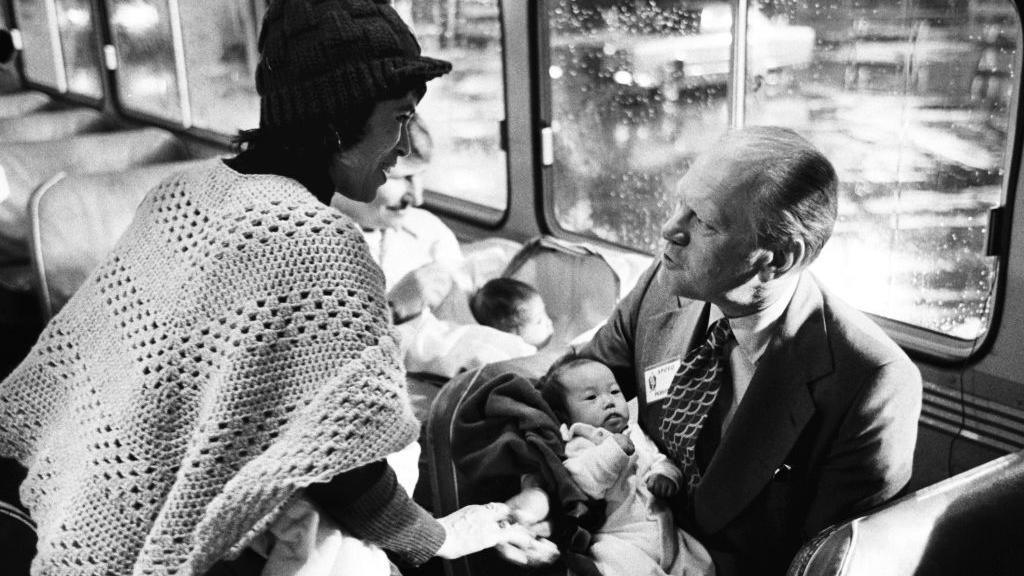

Their cries were heard by President Gerald Ford, who ordered Operation Babylift, taking 2,000 South Vietnamese children from orphanages to the United States.

The final flight filled with children and orphanage staff took to the skies as artillery fire came barrelling towards the runway.

President Gerald Ford with Vietnamese children as they arrived in the United States

'Playboy bunnies' carried Vietnamese babies off Hugh Hefner's private jet, who ordered it to travel to Vietnam to aid Operation Babylift

"The Vietnam War and Operation Babylift is not something that many people - including myself - know an awful lot about," Andy says.

"Part of bringing the play to the Fringe is to raise awareness of the historical event", Barton says.

"People always say sorry when they find out you are adopted, and I always replied 'Why? Don't be sorry'."

The show was originally performed in London as a full-length play of Barton's personal experience but in bringing the show to the Fringe the creative team decided to give it a more Scottish focus.

Despite a life working with music, the play was Andy’s first experience in the theatre industry. He wrote original compositions for the play, while Barton is the lead and sole actor.

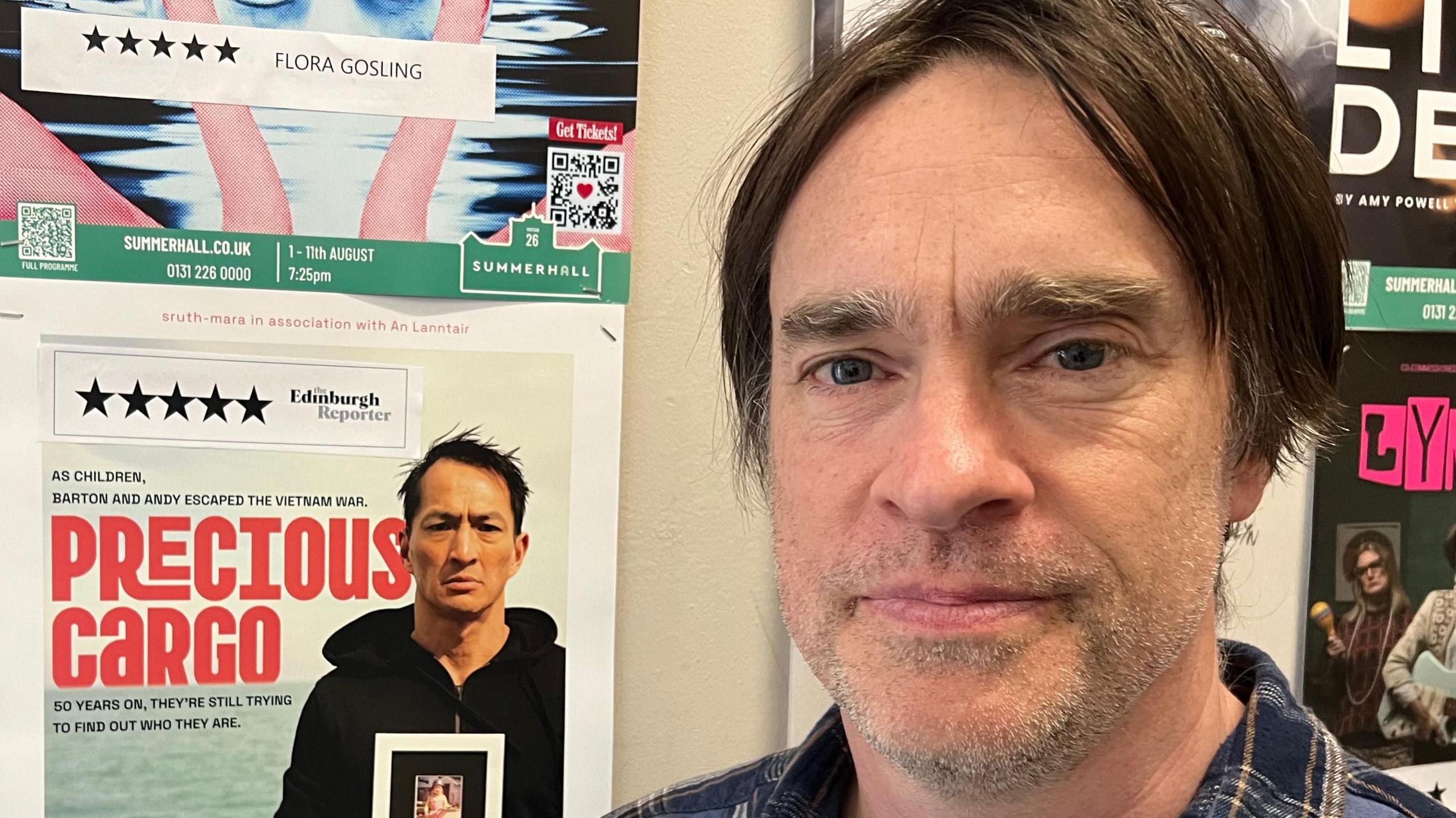

Andy and Barton were introduced to each other by a friend who was working on Barton's surf film, Laura Cameron-Lewis, who became the play's director.

Her husband Andrew Eaton-Lewis, then joined the Precious Cargo project as a producer to develop the script and find other orphans.

"I didn’t want it to be narcissistic," Barton says.

"Now that it's moulded with other orphans, it isn’t just my story, it's more than that."

The show features cardboard boxes - as they were predominantly used to transport Operation Babylift children

There are unanswered questions for many children taken from Vietnam.

Andy and Barton travelled back at different points in their life to experience the culture of their birth country.

Andy travelled to Ho Chi Minh City, the official name for Saigon, for a BBC2 documentary in 2004 to explore Vietnam for the first time.

Andy, who works as a music teacher, played accordion for children at the orphanage where he had been found.

He says his only link to his past was locating the street he was found on.

Barton was unaware of any living blood relatives until he recently discovered a second cousin through an ancestry website.

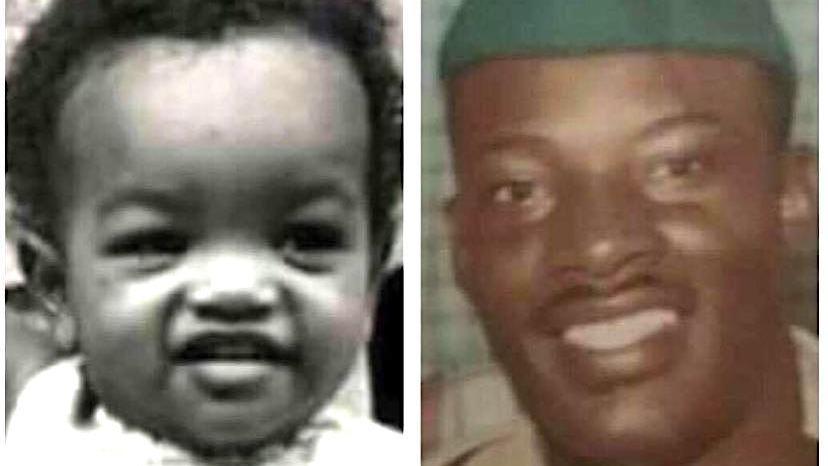

His search was aided by another Viet war orphan, Toni Angelique Harrison, who is still searching for her own mother.

Toni, who was raised in Bedfordshire in England, has her voice and story feature in the show and hopes the publicity could reunite her with her mother.

She travelled to the US to meet her father in 2018, an American soldier who fell for her Vietnamese mother.

Toni is just one of many Vietnamese war orphans who feature in Precious Cargo, still searching for their blood family

Baby Toni and her father, American soldier Lee Butler - who she met in 2018 through an online DNA test

For all the children of Operation Babylift, time is not on their side, the play's producer says.

With the 50th anniversary fast approaching, the tragic reality is that their parents might not be here for much longer.

"Operation Babylift was seen as controversial at the time," Mr Eaton-Lewis says.

"Was it the right thing to do?

He says: "The Americans exorcising their guilt over Vietnam, it all seemed quiet colonialist – all these white families, adopting Vietnamese babies.

"But talking to the various adoptees, they are all very positive about their experience.

"They are aware it is a strange thing to grow up in these very white environments, and some of them did experience racism and it was very difficult.

"But we have very much based this show on what these people have told us – and they were very grateful."

The play's producer Andrew Eaton-Lewis, introduced Barton to Andy along with his wife, Laura, who directed the play

Despite the successful flights, Operation Babylift began in tragedy as an operational failure caused the first plane to crash, killing 138 people, including 78 children.

In total, a huge humanitarian effort saw 3,300 Viet children - not all of them orphans - make it safely to western allies such as the USA, Canada, Australia, the UK and West Germany.

Many of the children were orphaned by war, but some had just been separated from their parents in the chaos.

But because of their coincidental meeting and work on the Fringe show, both men say it has brought their personal situation fresh in their mind.

Almost 50 years on, many are still searching for their biological families.

Precious Cargo is on Summerhall in Edinburgh until 26 August.

Thanks to Oli Charbonneau, lecturer of American History, at the University of Glasgow.

More on orphans affected by Operation Babylift

- Published26 February 2016

- Published1 March 2012