The endless legal battles over Muslim-donated lands in India

Waqf disputes can stem from a number of reasons

- Published

A controversial new law introduced by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government has put the spotlight on waqf, or properties donated by Indian Muslims over centuries.

Waqf is a tradition across many Muslim-majority countries, where these properties are used to house and operate schools, orphanages, hospitals, banks and graveyards.

The properties in India are managed by waqf boards formed by different state governments. A federal organisation called the Central Waqf Council coordinates their functioning.

But thousands of these land tracts, worth billions of rupees, have been mired in legal disputes across the country for decades.

For instance, in India's capital Delhi, there are more than a thousand of these properties, including mosques, graveyards and mausoleums. Emblems of the city's centuries-old Islamic heritage, they have been used for religious, educational and charitable purposes to benefit the community. At least 123 of them are locked in long-running ownership disputes between the city's waqf board and the federal government.

They form just a fraction of thousands of such cases fought by waqf boards across India against private parties - Muslims and non-Muslims - as well as government departments. It is one of the challenges that the federal government claims will be resolved through the new law, called the Waqf Amendment Act 2025, which has brought in dozens of changes to the existing system.

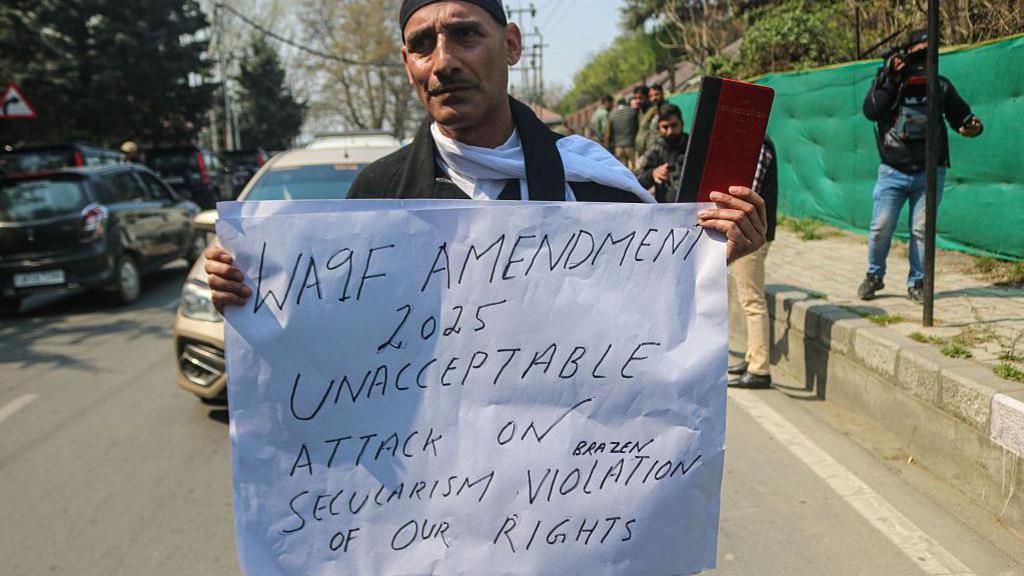

Many Muslim leaders and opposition parties have criticised the law, calling it an attempt to weaken the rights of minorities, and it has sparked protests and violence in some states. India's Supreme Court has also begun hearing a bunch of pleas challenging the law.

Waqf disputes stem from a number of reasons - unclear land titles, oral declarations of properties as waqf, inconsistent laws, collusion with land mafias and years of official neglect.

Government data shows that of 872,852 waqf properties in India (on paper), at least 13,200 are entangled in legal battles, 58,889 have been encroached upon and more than 436,000 have unclear status.

Waqf ownership was a matter of debate even during the British period

Some of these claims have attracted national attention. For instance, waqf boards in different states are accused of wrongly claiming ownership of a predominantly Christian village , externalin Kerala, several government buildings in Gujarat and a large tract of land used by farmers in Karnataka.

The federal government says waqf boards have declared ownership over 5,973, external of its properties across India - an assertion denied by the boards which insist they rightfully own these sites.

Some disputes are traced back to India's partition in 1947. In Punjab, more than half of the state's 75,965 waqf properties have been "encroached", a legacy of migration that left many Muslim estates in limbo. "Some owners fled to Pakistan, and others arrived and claimed the same properties," said Mohammad Reyaz, who teaches at a university in Kolkata.

In Delhi, the 123 disputed properties are claimed by departments under the federal urban and housing ministry, while the waqf says its ownership dates back to the British era and earlier. Attempts by governments and courts to resolve the issue have not been successful.

As far back as 1923, lawmakers in British-ruled India had flagged, external concerns over waqf properties slipping away from Muslim control. The MPs pushed for their registration, warning that managers supposed to take care of the properties were wrongly listing themselves as owners - a practice critics say continues even today.

Prof Reyaz says such disputes have increased as land prices rise.

"Not many cared for every piece of land 40-50 years ago, but as its importance has grown, members of the community or descendants of the donors have started claiming the waqf land, often resulting in disputes in places where people have lived for generations, either after buying or encroaching on the land," he says.

Disputes also stem from attempts by waqf boards to suddenly claim land they have long neglected. So, despite them being government organisations, the boards are being criticised for their unchecked power to claim properties.

Part of the concern is because of repeated assertions by media and politicians that the decision of the waqf tribunal - a specialised judicial organisation that hears waqf disputes - is final, says Mohd Ismail Khan, a Hyderabad-lawyer involved in several waqf-related cases. But the final authority, he points out, are higher courts.

The new law has sparked protests in many states

Even under the old law - which the government said gave "draconian, external" powers to claim property ownership - waqf boards frequently failed to safeguard their own interests.

Afroz Alam Sahil, a journalist who has extensively covered waqf-related issues, highlighted these weaknesses in 2011 with a question filed under the right to information law about Delhi's graveyards. The Delhi Waqf Board initially reported 562, later revising the number down to 488.

But in 2014, a waqf board official told him - in a BBC Hindi report - that only 70-80 graveyards remained under its supervision in the city.

This lack of clarity extends to other properties too. In 2008, says Mr Sahil, the Delhi Waqf Board issued a list of 1,964 properties under it in the city, but a federal government statement this month put that number at only 1,047. It's not clear what has happened to the 917 properties missing from the list.

The BBC has reached out to the Central Waqf Council and Delhi Waqf Board for comment.

While most stakeholders agree that the system needs reform, critics fear the new bill will not improve the situation.

A major cause for concern is the removal of a provision called "waqf by user" - which allowed properties to be designated as waqf if they had been used for religious or charitable purposes by Muslims over time.

According to government records, 402,000 waqf properties are classified as "waqf by user". This could be because they were orally donated decades or even centuries ago, without deeds or documents.

A federal minister has said in parliament that existing waqf-by-user properties - registered with the government before the new law came into force - will remain so unless their ownership has already been disputed. But it is not clear how many such properties have been formally registered.

Critics argue that eliminating this provision will spark new disputes and worsen existing ones as it could give rise to new claimants even for properties that have been actively used over the years.

One of the petitions submitted, external in the Supreme Court argues that since much of the waqf land is "not created under any deed" but was classified as "waqf by user", much of the properties will cease to fall under the category.

The removal of the "waqf by user" provision also brings into question a 1998 Supreme Court ruling that said "once a waqf, always a waqf", meaning once a property is donated as waqf, its character couldn't be changed.

Syed Zafar Mahmood, a former bureaucrat, said this change in the new law could affect tens of thousands of waqf properties.

"Very few properties will remain waqf assets, while the rest may cease to exist," he told BBC Hindi.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, external, YouTube, external, X, external and Facebook, external