Why do some fans think misogynistic chanting is OK?

Abusive chants about Manchester City's Phil Foden were made during Sunday's Premier League derby against Manchester United

- Published

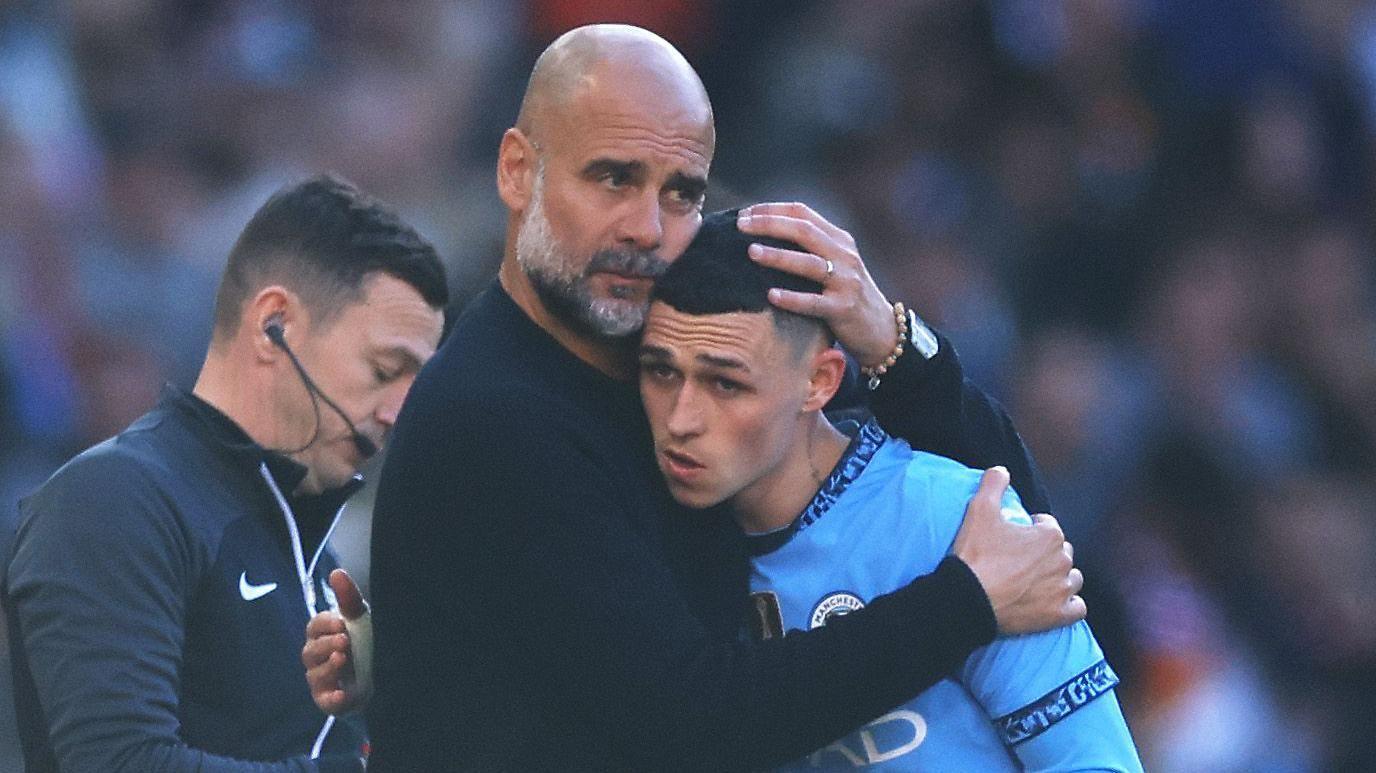

At Sunday's Old Trafford derby, Manchester City's Phil Foden was targeted by some United fans chanting highly abusive songs about his mother.

Foden's manager Pep Guardiola was quick to speak out after the game.

"Honestly, I don't understand the mind of the people involving the mum of Phil," he said.

"It's a lack of integrity, class, and they should be ashamed."

But why is misogynistic chanting happening at all, and given the Football Association's (FA) decision not to take action after the game in Manchester, is it being taken seriously enough?

Dr Mike Hope, from Keele University, is an expert on football policing and crowd behaviour.

Before moving into academia, he spent 23 years as a police officer, ultimately reaching the rank of inspector with Devon & Cornwall Police.

He spent a lot of time as a "spotter", watching out for known trouble-makers, gathering operational intelligence, and helping to defuse potential flashpoints at football games.

Dr Hope is part of the university's Enable Project, external, which brings together seven police forces, football clubs and governing bodies.

He says its aim is to make the policing of football "more effective, reduce disorder and improve relationships between fans and police".

Hollie Varney, from the anti-discrimination group Kick It Out, says sexist chants within stadiums can make women feel unsafe or unwelcome

Dr Hope thinks the abuse suffered by Foden can be explained, though not justified, by a combination of factors.

He points out that, while the chanting was widely condemned, "to some people it might be viewed as acceptable banter".

Former Watford and Birmingham City striker Troy Deeney told talkSPORT: "I take Pep's point, but it's a derby - people are emotional.

"We shouldn't accept it, but it's been going on since the beginning of time.

"It's part of the game unfortunately - it is what it is."

Deeney said former Chelsea and Italy forward Gianfranco Zola had once told him that footballers were "paid to not have feelings".

Very few people would be prepared to shout verbal abuse at strangers in a park, street or supermarkets, though.

Troy Deeney was briefly manager of Forest Green Rovers before continuing his career as a pundit

So what is it about football? Why do some fans originate chants and why do many more join in?

"It's about expressing your identity as fans, as a collective," says Dr Hope before adding that this was more keenly felt in some areas of stadiums than others.

All football grounds have sections where the most vocal fans congregate - not just in Britain, but in continental Europe where groups known as "ultras" sit and stand together.

While these fans generate much of the atmosphere at games that is valued so highly by other supporters and broadcasters alike, Dr Hope thinks they can sometimes straddle the boundaries of what is deemed to be socially and legally acceptable.

"Fans distract and intimidate opposition players - even more so in derbies - and this is where the line can be trodden over," he says.

In addition, some individuals can feel "empowered" by being part of a crowd of thousands.

Dr Hope also thinks some fans get "caught up in the moment" during matches and - were they to be given time to reflect - many of them would change their views about where to draw the line between banter and abuse.

Racism, homophobia and other forms of abuse

Dr Mike Hope spent many years in football policing

Thanks to stronger enforcement and better education, Dr Hope says the levels of racism we saw in the 1970s and 80s have reduced significantly within stadiums.

He says we have "seen a similar journey" in recent years when it comes to homophobia on the terraces.

Tragedy chanting - when rival fans taunt each other about tragedies such as the 1989 Hillsborough Disaster or the 1958 Munich Air Disaster - is also on the wane, according to Dr Hope.

While acknowledging some isolated incidents still happen, he thinks most fans "police themselves", for example by not joining in the offensive chants.

"When they won't get involved, there is a lack of traction for the chant to gain hold," he explains.

Dr Hope says "a lot of work" has been done both to identify and prosecute offenders (for instance through high-definition CCTV cameras) and better educate fans.

He also points out that it has never been easier for fans to discretely report offensive and abusive behaviour or chanting - for example by sending text messages to the club about the block, row and seat number of those causing trouble.

In plain language, Dr Hope says: "You can report concerns now in ways that won't risk you getting your head kicked in."

Misogynistic abuse

Misogyny and sexism do not exist in a vacuum, argues Dr Hope.

"Problems are society-wide but football is a vehicle through which they are exposed.

"The FA, clubs, the Premier League... and police have roles to play in both education and enforcement, for example by clubs issuing bans, police action being taken."

Ultimately, he argues that a combination of education and enforcement are key.

Dr Hope says police match briefings increasingly consider the need for officers and football clubs to be aware of misogyny and violence towards women and girls.

He says there is now a lot more awareness and emphasis being put on these areas of discrimination, in addition to a greater focus on safeguarding.

'Revise definitions'

FA rules do prohibit abusive chanting and discriminatory behaviour from fans.

Rule E20 states clubs are responsible for ensuring their supporters "refrain from improper conduct", which includes "a reference, whether express or implied to any one or more of the following: ethnic origin, colour, race, nationality, religion or belief, gender, gender reassignment, sexual orientation or disability".

The FA says it investigates all allegations of discriminatory conduct by spectators. Its rules also state a club is "likely" to face disciplinary actions if there is "sufficient evidence of mass discriminatory chanting".

No action is planned against Manchester United over the Foden abuse, however.

The BBC understands the chants would have been deemed discriminatory had they have been directed at a female player.

But given they were aimed at a non-participant in the game [Foden's mother] the rule does not apply.

In light of what happened at Old Trafford and the ensuing fallout, Dr Hope thinks the FA may revise its definitions.

Hollie Varney, chief operating officer of the anti-discrimination in sport group Kick It Out, believes much stronger action is needed to tackle sexism and misogyny.

She told the BBC: "We've seen several incidents of sexist and misogynistic mass chanting in men's football this season, yet too often the response from football falls short.

"Sexism isn't 'banter'. Hearing sexist chants echo around a stadium doesn't just affect the players involved or those directly targeted, it creates an environment where women can feel unsafe or unwelcome."

In February, the organisation's chief executive Samuel Okafor pointed to research it had done with 1,500 female football fans.

"One-in-four still feel unsafe going to games and 52% said they experienced sexism within a stadium," he said.

"There's still a huge amount of cultural work to do to make the game more inclusive."

The Kick it Out campaign was established in 1993 to tackle discrimination in football

Action can be taken, though.

In November 2023, two fans were arrested for directing misogynistic abuse at referee Rebecca Welch during Birmingham City's Championship match against Sheffield Wednesday at St Andrew's.

The two teenagers were eventually referred to Kick it Out's fan education and engagement manager Alan Bush.

"I'm looking to change their behaviour and change their attitude," he said.

"I use a lot of reflective questions, for example: 'If that was your sister or your grandmother and they were on the end of that sort of abuse how would you feel?'

"I get them to a point where I start dismantling their attitudes and their views."

Get in touch

Tell us which stories we should cover in Greater Manchester

Listen to the best of BBC Radio Manchester on Sounds and follow BBC Manchester on Facebook, external, X, external, and Instagram, external. You can also send story ideas via Whatsapp to 0808 100 2230.

Related topics

- Attribution

- Published7 April

- Attribution

- Published6 April

- Attribution

- Published11 September 2024