Could new implants treat depression, dementia and chronic pain?

The implants will change the way our nerve cells behave and interact

- Published

Tiny electronic implants have already transformed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people in the UK, from pacemakers that control heart conditions to cochlear implants that improve hearing.

Now a partnership of people from the health, science and business sectors in Cambridge has been awarded millions of pounds to fast-track radical new technologies that could do the same for brain health.

Innovators from across the UK will be offered the chance to test their ideas in the city. The most promising will be supported to become patient-ready treatments for people with conditions like depression, dementia and chronic pain.

One of the lead scientists in the group, Prof George Malliaras, hopes it could support his new project.

In an engineering lab at the University of Cambridge, his team is developing brain implants to treat neurological and mental health conditions which, the university estimates, will affect four in every five of us.

"Brain implants can give us a new treatment for diseases that are currently either untreatable or ineffectively managed by pharmaceuticals," Prof Malliaras explains.

"The list is ever expanding, but we're talking about brain and spinal cord injuries, Parkinson's, dementia, depression, OCD, and it's looking promising for rheumatoid arthritis and Type 1 diabetes too.

"It's a humbling project to work on, but also intensely motivating."

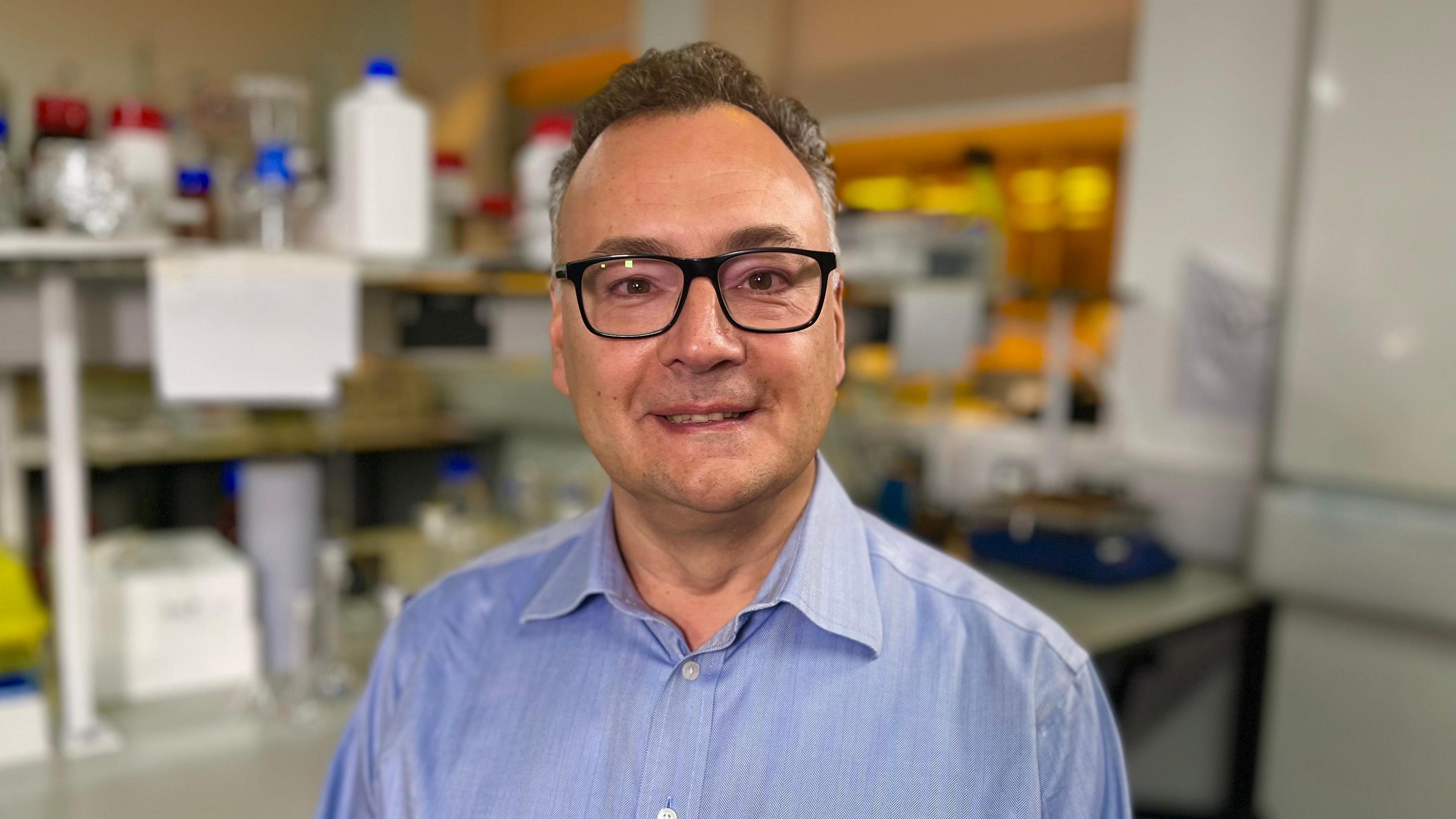

Professor of technology George Malliaras says brain implants have the potential to treat a vast range of conditions

The implants work by sending out small electrical impulses that change the way our neurons behave.

Neurons are nerve cells, which send messages between our body and our brain through electrical signals. They affect the way we walk, talk, eat and breathe. By changing the way they work, it is possible to eliminate pain or re-stimulate parts of the brain affected by disease or injury.

"We already know that we can use electrical impulses to diminish the tremor for some with Parkinson's disease, external," says Prof Malliaras, "but we want to put together teams of engineers, clinicians and people in industry from across the UK to take this sort of technology much further".

Dr Chaoqun Dong is one of the University of Cambridge engineers working on a range of new medical implants

The size of the device is one of several challenges for the team to overcome.

"The electrodes which come out of the implant need to be no bigger than a single neuron. That's five times smaller than the diameter of a human hair," says Prof Malliaras, "but if the device is too small it can struggle to communicate with the body, and it is harder for surgeons to work with, so it's a balancing act".

They must also ensure the implant can be mass produced, is cost effective and exposes the patient to as few side effects as possible.

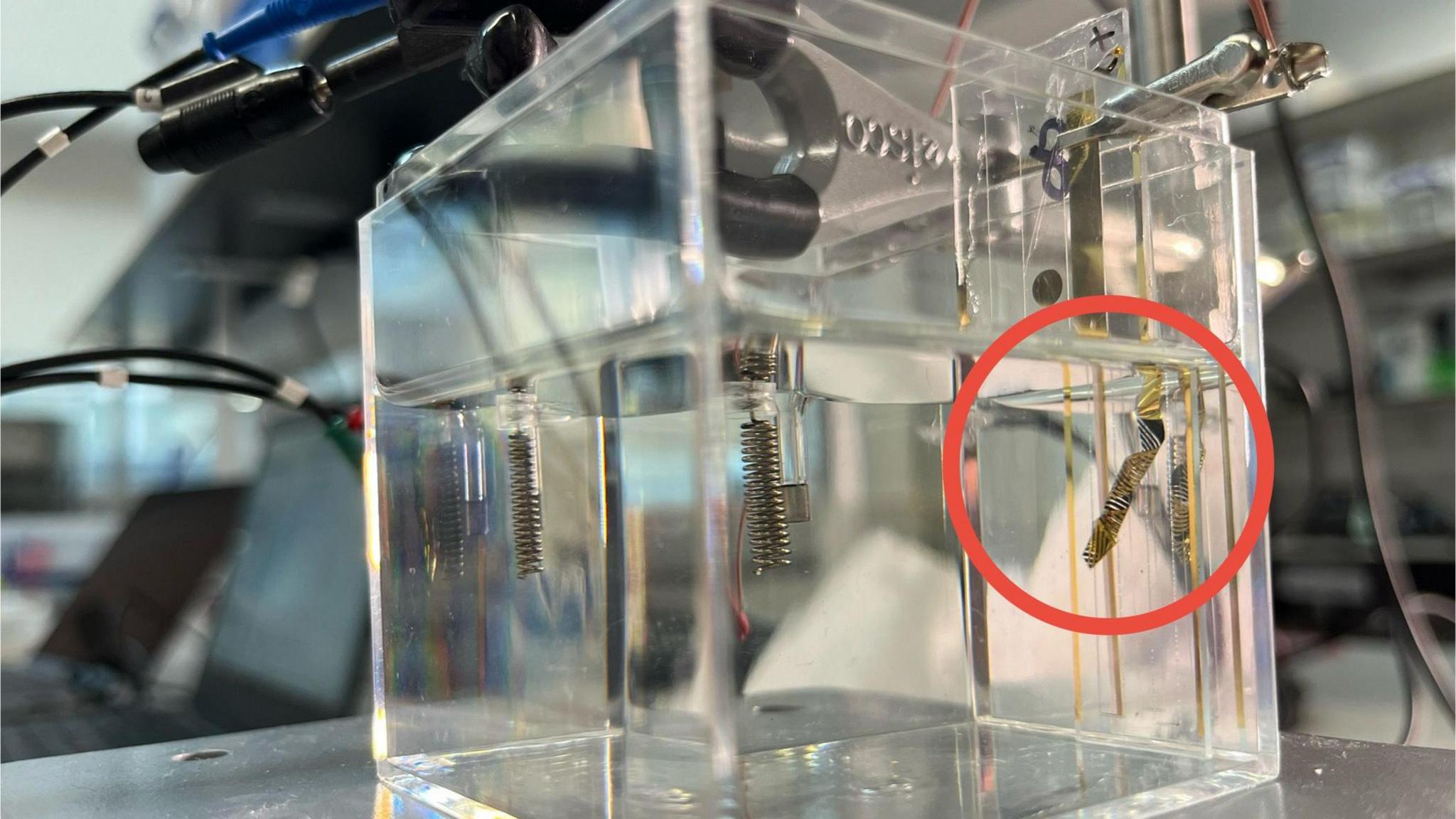

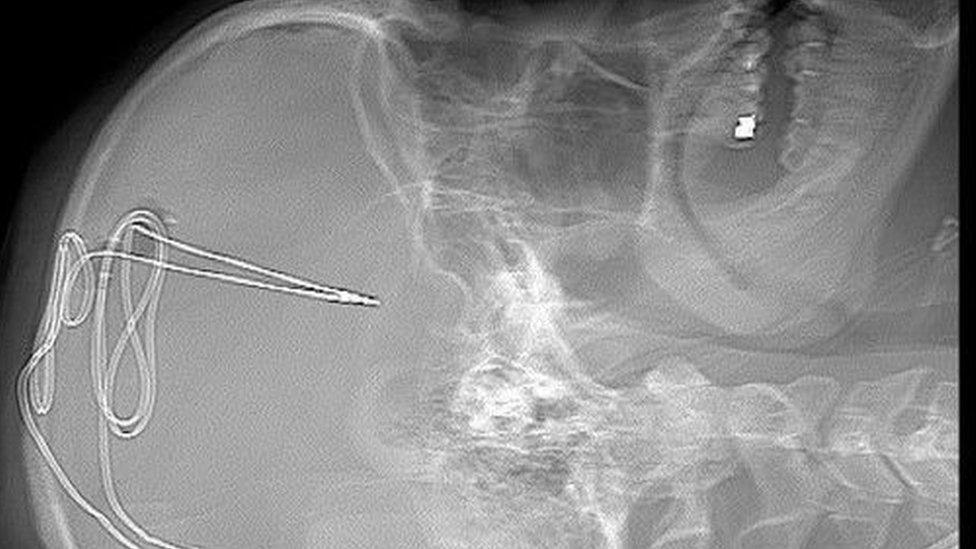

When electricity is passed through this ribbon-like implant it can coil around a fragile nerve

Medical implants are not new to these engineers. Dr Chaoqun Dong is developing a device that can wrap around fragile nerves without damaging them.

In a glass cube, she works on a small ribbon-like structure suspended in liquid. It is made from a polymer lined with gold. When electricity is passed through it, it spontaneously coils up into a spiral. These devices would be able to monitor the impulses coming through a nerve during complex surgery, but also stimulate the nerve.

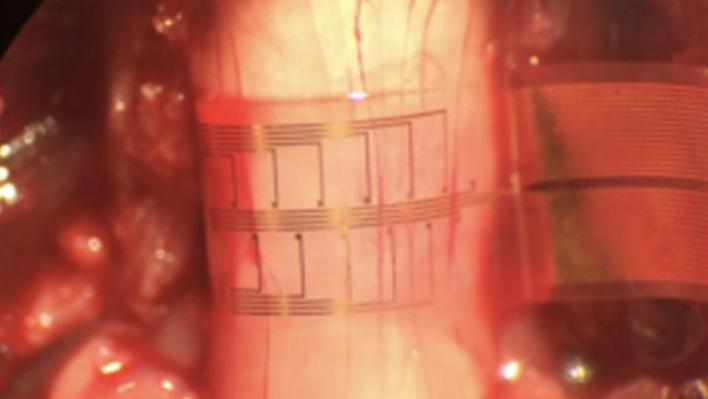

An implant self-wrapped around a nerve to monitor and apply electrical impulses

Electricity has been used to treat conditions for many years - electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for severe depression, external and bipolar disorder began decades ago. But Prof Malliaras believes that while implants are an invasive procedure, they could offer advantages over one-off treatments.

"Implants can constantly monitor the brain to detect abnormal activity and then correct it more gently when needed," he says.

In 2021, scientists in the US reported promising results from an early study using brain implants to treat severe depression.

The Cambridge Partnership is being funded for three years by ARIA, external - a government-backed science agency.

Professor Malliaras says he is confident that within that time they will have come "a long way" to making viable new treatments.

Get in touch

Do you have a story suggestion for Cambridgeshire?

Follow Cambridgeshire news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, external, Instagram, external and X, external.

You may also be interested in

- Published24 June 2024

- Published24 May 2023

- Published8 November 2019

- Published4 October 2021