Climate change made UK's waterlogged winter worse

Brussel sprout crops have been hit by the wet weather

- Published

Climate change is a major reason the UK suffered such a waterlogged winter, scientists have confirmed.

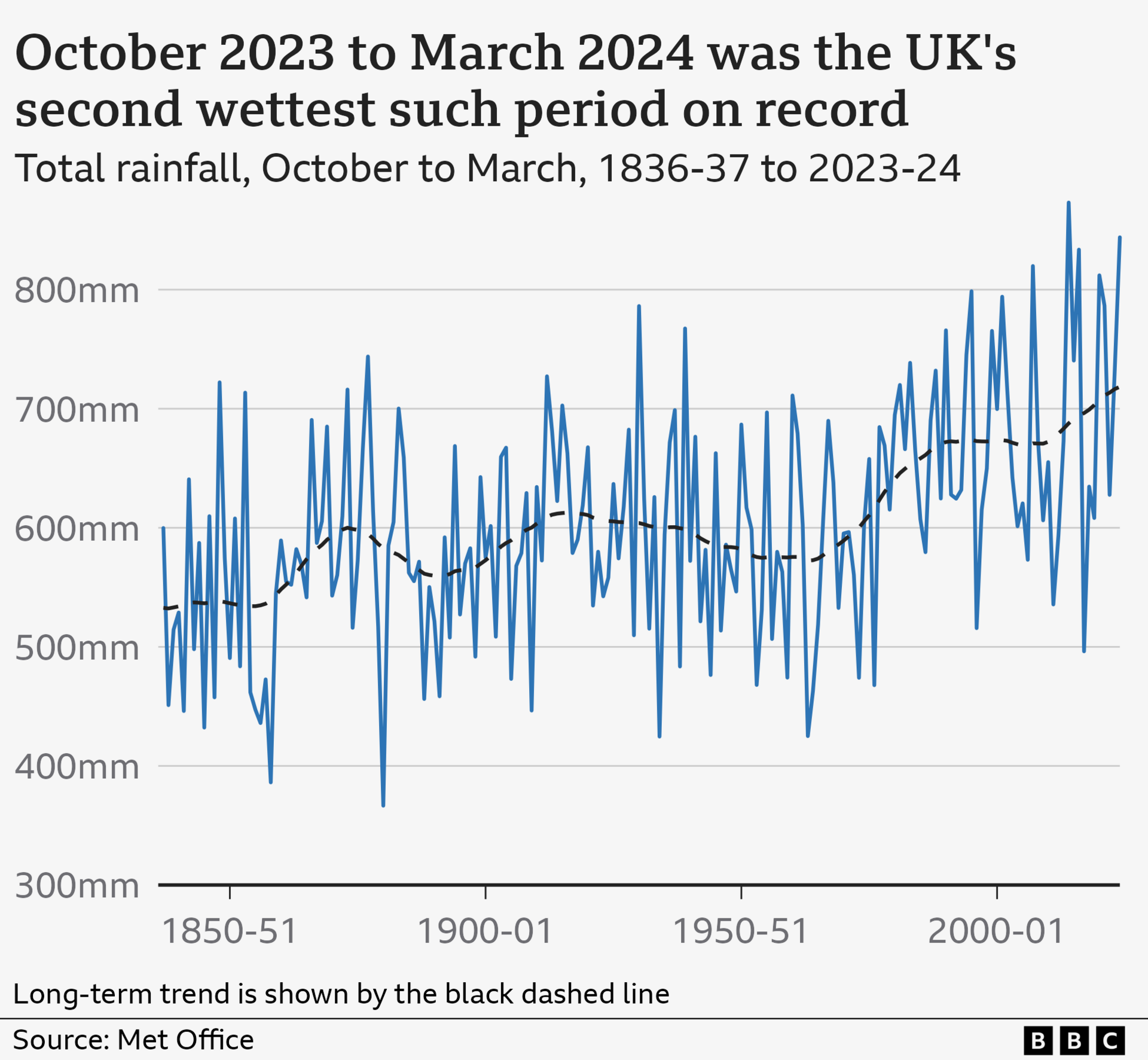

It was the country's second wettest October to March period on record and a disaster for farmers, who faced flooded fields during a key planting period.

Global warming due to humans burning fossil fuels made this level of rainfall at least four times more likely, according to the World Weather Attribution group.

One farmer in Lincolnshire told the BBC that a third of his farm could not be planted in time this year.

Colin Chappell, a fourth generation farmer on the banks of the River Ancholme in Lincolnshire, who produces food including peas, oil and wheat, says he will only produce half what he would usually expect.

“There are some farms in the valley that will not see a harvest at all this year. That hasn’t happened here since 1948,” he says.

He believes the future for many farmers is bleak.

“If you’ve got nothing to bring in from your fields, what do you sell?”

“Supermarkets will just move to imports so the consumer won’t feel the impact of British farms closing down until it’s too late.”

Colin Chappell says the wet conditions mean he may only produce half what he would usually expect

The UK and Ireland’s wet winter is the latest in a long line of recent extreme weather events to have been worsened by global warming, as the impacts of climate change begin to hit home.

Storms are, of course, a natural part of UK winters, and these low pressure systems are mainly driven by the polar jet stream – a band of strong winds high up in the atmosphere.

But climate scientists have long warned that a warmer planet will bring more intense rainfall in many parts of the world.

The air can generally hold around 7% more moisture for every 1C of warming, and the last decade was about 1.2C warmer than pre-industrial times.

More on extreme weather

Deadly Dubai floods made worse by climate change

- Published25 April 2024

Deadly Africa heat caused by human-induced warming

- Published18 April 2024

The scientists modelled what this winter might have been like without climate change and compared it to the reality of our warmer world.

They found that the total amount of rainfall between October 2023 and March 2024 would have been a one-in-80-year event without humans heating up the planet, but is now expected once every 20 years.

Meanwhile, the amount of rainfall on the stormiest days increased by about 20% on average, due to climate change.

“Until the world reduces emissions to net zero, the climate will continue to warm, and rainfall in the UK and Ireland will continue to get heavier,” warns study lead author Sarah Kew, a researcher at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

Farmers hit hard

The struggles faced by UK farmers this winter highlight the urgency and challenges of adapting to more frequent and intense extreme weather through measures like flood defences.

Last year, the government’s independent advisers on climate change warned that the UK was “strikingly unprepared” for its impacts.

But adaptation can be far from simple.

The reality is that “some of the best farmland is the low-lying land in the UK and you can’t move that elsewhere,” explains Tom Lancaster, head of land, food and farming at the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), an independent think tank.

You don’t have to be in a flood plain to be impacted by the wet winter as a farmer either, he adds.

“It’s more about soil type. For example waterlogged clay soil stops farmers being able to get machinery onto their fields or drill a crop.”

Fields were waterlogged for months on Colin Chappel's farm

The government’s sustainable farming incentives – which pay farmers to adopt and maintain sustainable practices - could be a “potential lifeline for farmers” as the UK continues to face more extreme weather, the ECIU says.

Colin Chappell says his farm in Lincolnshire will only make it through by relying on this scheme and a small buffer from previous years. He fears others may not be so lucky.

“How can anyone half their production and still expect to be around next year?” he asks.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to get exclusive insight on the latest climate and environment news from the BBC's Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt, delivered to your inbox every week. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.