‘I agree with Nick’: How to win a TV debate

- Published

With the first BBC election debate on Friday evening - and more to follow, people will be watching to see what difference it makes to the campaign. Experts consider how politicians are preparing and the pitfalls they should avoid on the night.

Election debates feel like they have been around forever, but they are a relatively new thing in the UK.

There is no rule that says they have to take place, but whichever party is behind in the polls will invariably challenge the frontrunner.

And no politician in an election campaign wants to be accused of running scared. The template was set at the first debate in 2010....

“I agree with Nick!”

It became the one of the catchphrases that would define the campaign.

That election saw the first ever televised TV debate between the then three main party leaders, Prime Minister Gordon Brown, his Tory challenger David Cameron, and the Lib Dems' Nick Clegg.

The self-styled outsider seemed most at ease at the podium, looking down the barrel of the camera and appealing directly to the viewers.

His message: “I believe the way things are, are not the way things have to be” and a number of his arguments, the other two leaders agreed with.

But it didn’t do him much good. The Lib Dems lost seats in the election, despite their leader’s favourable personal ratings.

The positive coverage frustrated David Cameron though, says his former director of communications, Sir Craig Oliver. And that is why David Cameron - now Lord Cameron, Foreign Secretary - minimised the number of debates he did in 2015.

Sir Craig says a lead in the polls is like a Ming vase, precious and fragile, and the debate, a polished floor the leader must carry it across.

“Everyone wants to have election debates apart from the people who are in the lead. And although they say they want them, in reality they are trying to protect their lead.”

Theresa May did not take part in any TV debates in the 2017 election. The then-PM went on to lose her Conservative majority in the House of Commons.

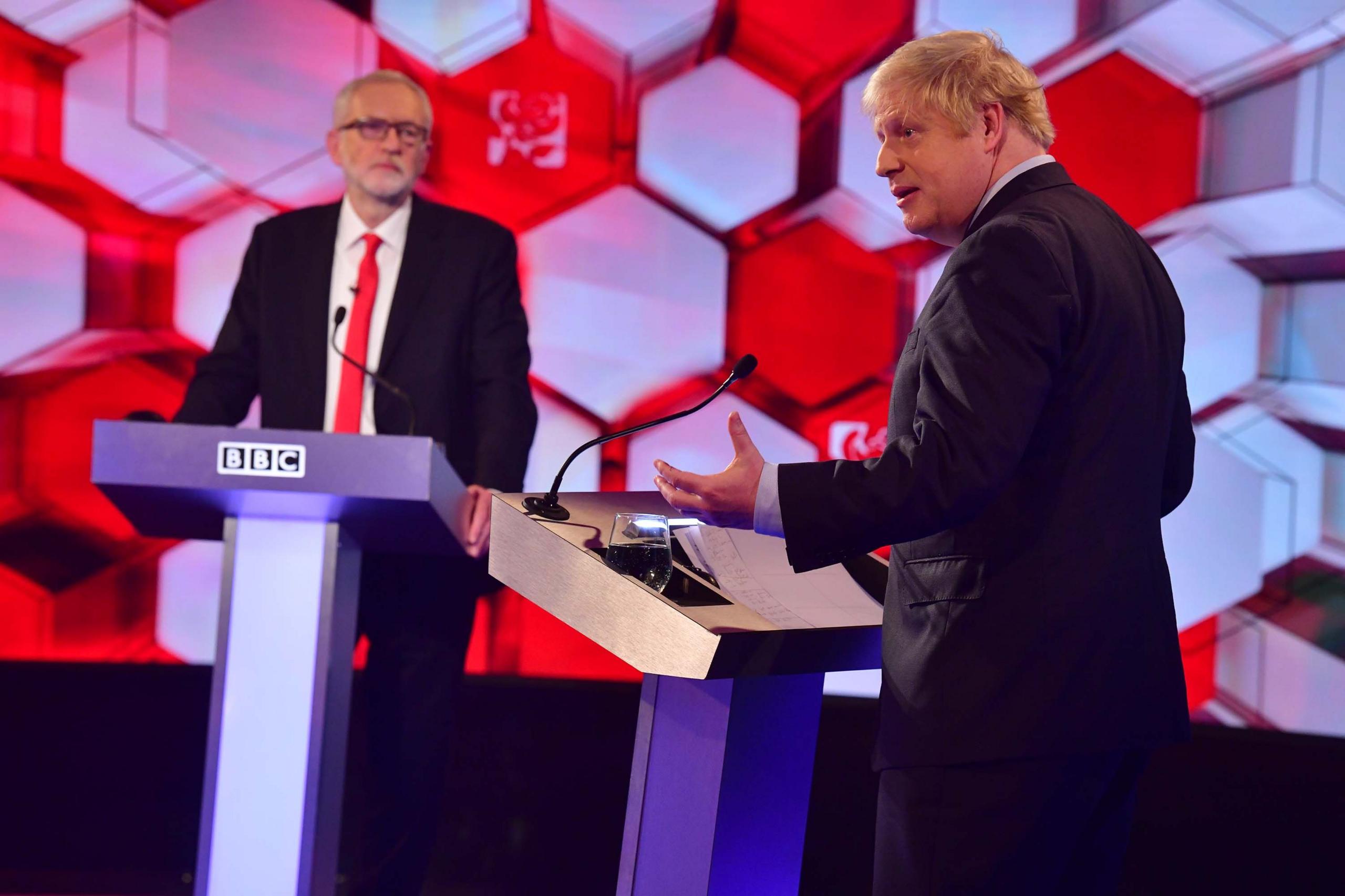

Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn went head-to-head in 2019

There have been leaders' debates for the last four elections of all shapes and sizes: some with multiple party leaders, others head-to-heads with the two main parties.

And the pitfalls in all formats are similar.

John McTernan, Tony Blair's former political secretary, advised former Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy and Australia's ex-prime minister Julia Gillard ahead of their televised debates. His advice remains, above all, leaders must be authentic.

“Avoid making dad jokes. Dad jokes are not funny and dad jokes are not zingers. Zingers come from people who are naturally witty. Don’t pretend you are naturally witty, just be natural.”

How much impact can TV debates have?

- Attribution

How to watch Tuesday's TV election debate

- Published2 July 2024

More than 9 million people watched the first election debate in 2010. But the viewing figures have declined since.

So why bother?

Joe Twyman, co-founder of the pollsters Delta Poll, says it is as much about the clickbait produced from those “zingers”, that can be reproduced after the event, as it is to be perceived to have won the debate.

“The debates have the potential to make an impact but in reality it’s unlikely to do so. If it doesn’t, it’s not going to be about the immediate response afterwards, it’s going to be about the days, perhaps weeks, that follow. As clips and comments and analysis is distributed by broadcasters but also crucially by social media.”

The first BBC debate takes place on Friday at 19:30 BST on BBC One and BBC News.