'My children haven't been to school since January'

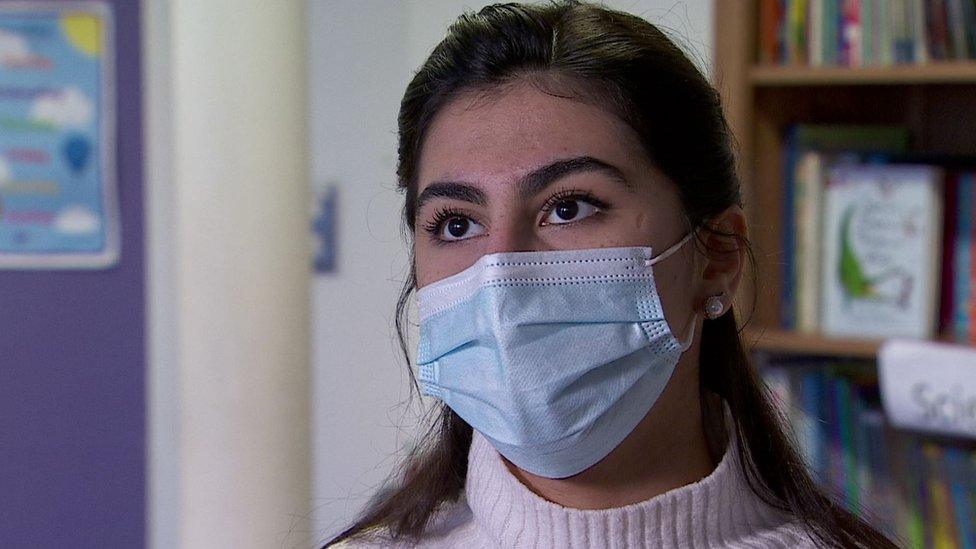

Nasra Ali's children have been unable to go to school since asylum was granted

- Published

Nasra Ali’s children haven’t been to school since January, and she doesn’t know when they will be able to return.

The mother of five is Somali and has been living in Northern Ireland since August 2021.

But after being given accommodation by the Home Office during the family’s application for asylum, she now finds herself without a permanent home.

That’s because when asylum is granted - and a person is recognised as a refugee - they lose their right to stay in Home Office accommodation.

Local councils then become able to provide housing assistance.

Whether applicants can stay in the same area depends on things like how long they have lived there, and whether they have family in the area or are at risk of homelessness.

Waiting lists for accommodation are often long, and migrants may be housed in B&Bs, hostels or hotels on a temporary basis.

“It is very difficult," Ms Ali said.

"The children get used to going to school in the morning, a normal routine. They come home. That doesn’t exist any longer."

She has two girls, aged nine and four, twin boys who are six, and a two-year-old son.

During her asylum application her four school-aged children attended St Paul’s in west Belfast, where they were learning English and thriving.

Ms Ali pictured with three of her five children

Asylum granted - but what happens next?

But in the past five months, since gaining asylum, Ms Ali and her children have been living in temporary accommodation in Limavady, Ballymena and, currently, a hostel in Portrush.

The children had to leave their west Belfast school.

“It was very important for me to get safety and settlement but when I see the situation I am living now with my children - that [asylum seeker status] was a better situation than I am in now," she said.

“My daughter said to me: ‘Mom, when we didn’t have refugee status, we had a home and we used to go to school but now I think we were better off being asylum seekers.’”

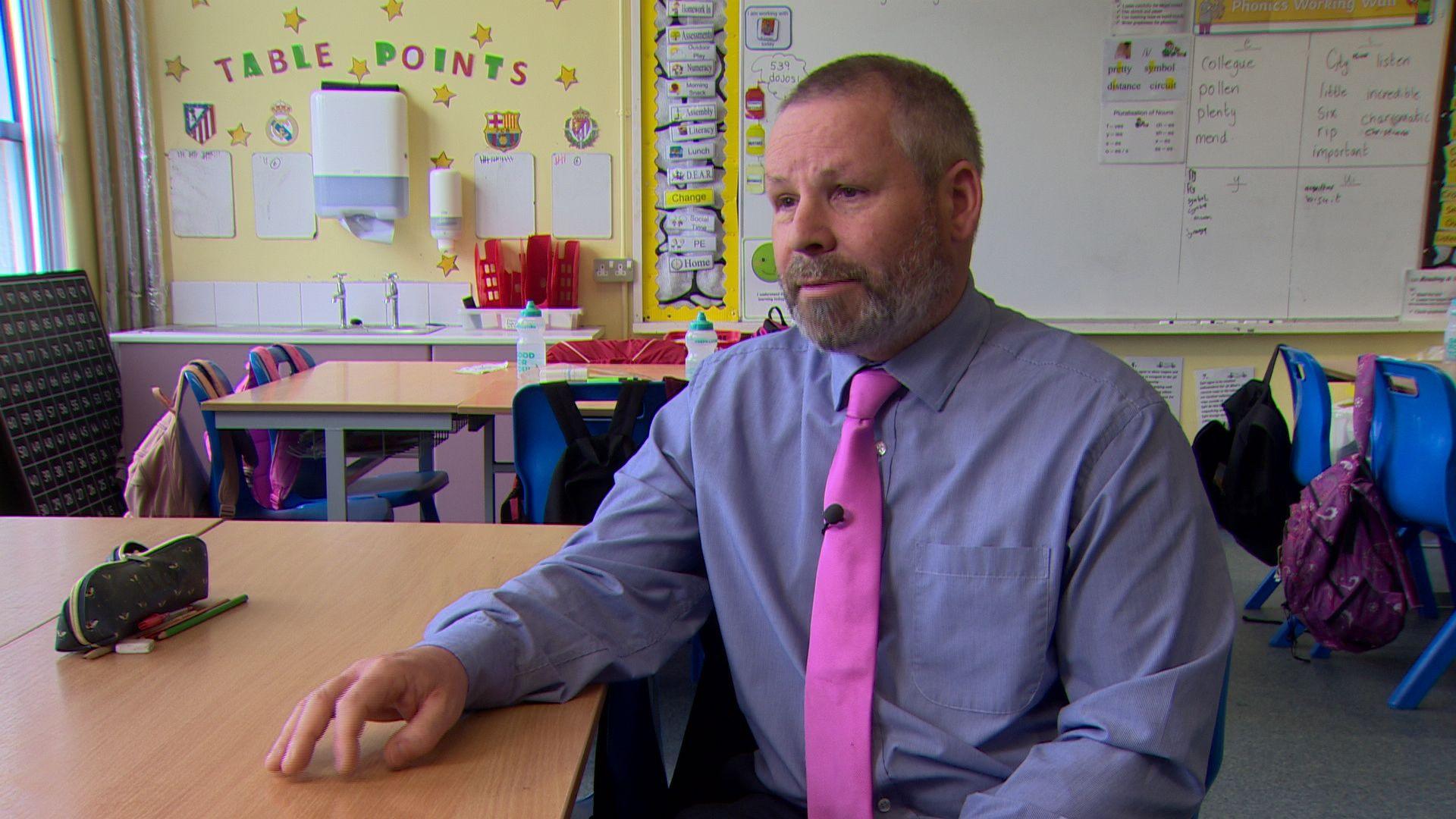

The principal of St Paul’s said 15 pupils had left the school between Christmas and Easter

Ms Ali's situation is one that Sean McNamee is all too familiar with.

The principal of St Paul’s School in west Belfast said that between Christmas and Easter, 15 pupils had left the school.

They were from families who had been granted asylum, lost their Home Office accommodation and were moved outside of the area, to places as far away as Londonderry and Enniskillen.

Some families continued to travel to the school, while others like Ms Ali's have never returned.

Mr McNamee said some of his pupils had been picked up early by parents who had just found out they had to move out of their homes.

A third of the pupils in St Paul’s are from so-called ‘newcomer’ families, says the principal

“It’s an awful wrench for them to be taken away,” he said.

“For some, they have come from trauma, they’ve spent a bit of time getting to know us, building relationships, building trust and that’s been taken away almost instantaneously.

“For the children left behind, their friendships are broken.

“I don’t want children here to feel relationships have been undermined and that children here are reluctant to make new relationships because the nature of asylum-seeking families is very transient. I don't want that to happen.”

He said 30% of the pupils in St Paul’s were from so-called newcomer families.

What housing is there for asylum seekers?

The Home Office provides UK figures for the number of asylum applications granted but does not give a breakdown of figures by location.

The Northern Ireland Housing Executive is responsible for their housing needs.

Its chief executive Grania Long said 30% of households living in hotels in Belfast were “households who have recently arrived and received leave-to-remain status”.

She said this had placed “added pressure” on the Housing Executive.

Ms Long explained that housing was not always available in areas that people wanted to live in.

“Sometimes we have to advise people, if you choose an area, you could be waiting for a very long time," she said.

As for Ms Ali, with the constant moving, she said she was reluctant to enrol her children in another school.

Asked how difficult it was to listen to her children’s questions about when they would get a house, she replied: “Very sad, I cry all the time."

In a statement, the Housing Executive added: “We acknowledge the disruptive nature of the current housing circumstances for the whole family and are working to find a permanent, appropriate housing solution.

“We would like to reassure them that we are committed to finding a long term and more permanent home for the family as soon as possible.”

Related topics

- Published23 October 2023

- Published30 April 2024

- Published11 December 2021