Prisoner early release begins to ease overcrowding

- Published

Up to 1,750 offenders have spent their last night in prison ahead of being released under the Ministry of Justice’s emergency plan to ease the overcrowding crisis in jails.

Releases are due to begin on Tuesday morning as governors unlock cells under the plan to free up 5,500 beds.

One charity has warned that women and children will become the unintended victims of the emergency plans - while rehabilitation specialists fear any rushed releases will compromise vital work in turning around the lives of some offenders.

The chief inspector of prisons told the BBC his “biggest concern” was whether everyone released had accommodation to go to, a crucial part of stopping ex-offenders becoming homeless.

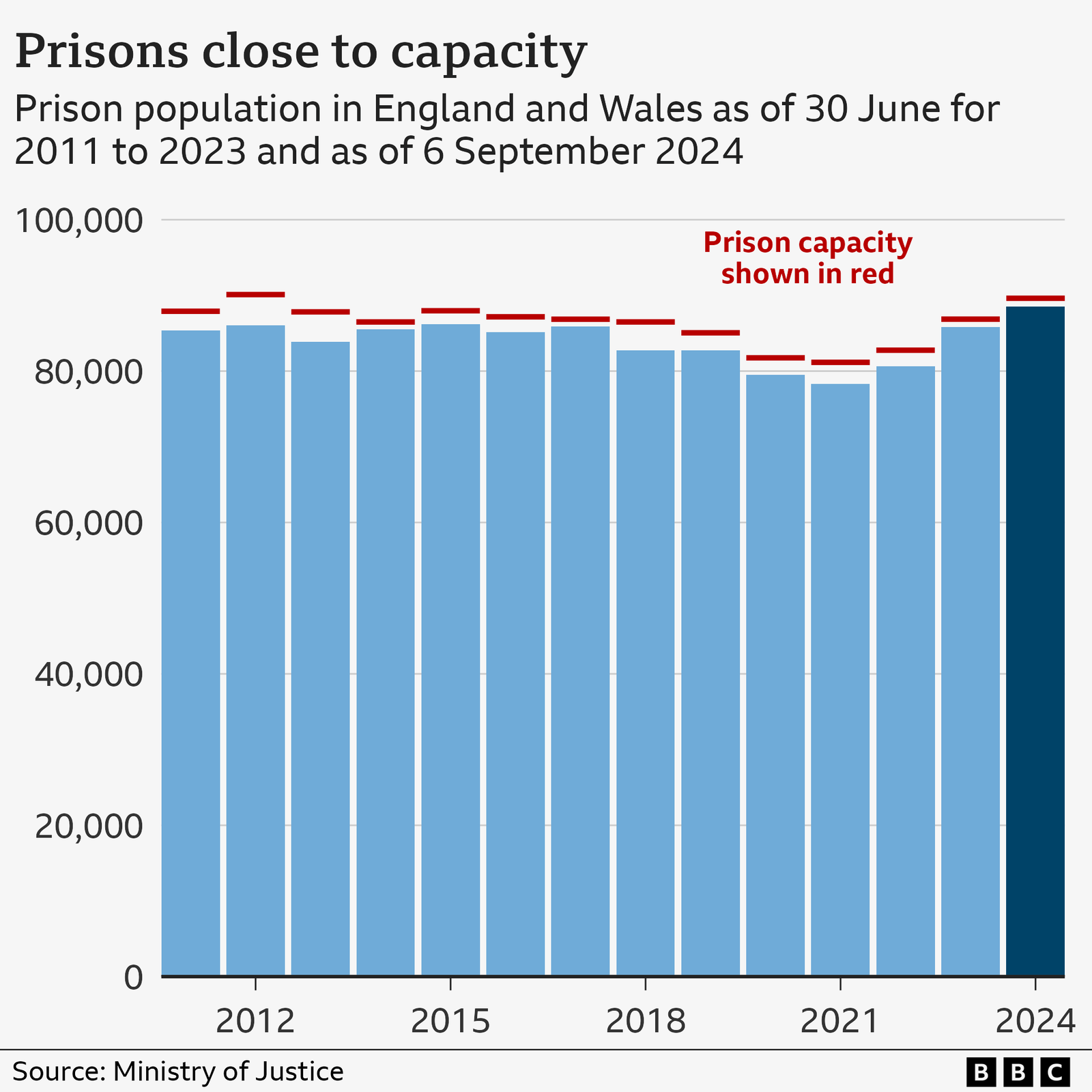

Last week prisons reached a record population of more than 88,500. That meant almost all of them were full, a situation that had been coming for months but had been exacerbated by the summer’s riots.

Under the emergency plans announced in July, offenders in jails in England and Wales serving sentences of fewer than five years will be released on licence into the community after having spent 40% of their term in jail, rather than the usual 50%.

On 22 October the scheme will be expanded to include offenders serving fixed sentences of more than five years.

The plan excludes offenders jailed for violent offences with sentences of at least four years, as well as sex offenders and domestic abusers.

The release licence means offenders will be subject to restrictions for the rest of their sentence, including curfews and tagging, and will be supervised by probation officers.

The scheme was triggered by the incoming Labour government days after the general election, but officials had already been drawing it up when the Conservatives were in power.

Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood said: "We inherited a prison system on the point of collapse. This is not a change that we wanted to make.

"It was the only option left on the table, because the alternative would have seen the total collapse of the criminal justice system in this country.

"We would have seen the breakdown of law and order, because courts would not have been able to conduct trials and the police would not have been able to make arrests."

Labour delayed implementing the new release rules until this week to give prison governors, the probation service and resettlement and rehabilitation organisations time to prepare.

Martin Jones, the HM chief inspector of probation said that there had been “a huge amount of pressure” on its officers over last eight weeks – but there was a genuine risk that some offenders would have nowhere to go.

He paid tribute to the frontline staff who had done a "huge amount of work" to prepare, but warned there will be "pinch points" in the coming days and weeks, particularly around accommodation.

Mr Jones said that within days or weeks, those released today will breach the terms of their probation licence and be sent back to prison, a risk that is "almost bound to happen”.

"There is also, I think, a certainty that some will reoffend," he said, and added that the risk of serious offences are rare but a risk that cannot be eliminated.

Isabelle Younane of Women’s Aid said that while the charity recognised that overcrowding was a serious issue it feared the emergency policy was coming at the price of the safety of women and children.

“The early release scheme relies heavily on an already overstretched and struggling probation service,” she said.

On Saturday Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer said that ministers were “doing everything” to ensure domestic abusers are not released early.

The Victims' Commissioner has warned some people have not been informed of the early release of the person responsible for committing a crime against them.

Baroness Newlove said this would be "distressing” for many victims and that people's safety must not be "in any way compromised".

The BBC has contacted the Ministry of Justice for more information.

Each former prisoner must meet their probation officer on the day of their release to ensure they understand the restrictions in their release licence. That may include curfews or bans on entering areas connected to their offending or to approach victims.

Yvonne Thomas, chief executive of The Clink, a charity that has a long history of training offenders for work, warned it was crucial that people leaving prison got a safe and secure start to minimise the risk of them re-offending.

“The last four to six weeks since the announcement has been quite challenging,” she said.

“The knock-on effect is that if resettlement is not properly planned, then resettlement fails. Recalls to prison are going up and the whole thing has become really dysfunctional.

“These releases are going to be challenging and put more strain on us.”

Ms Thomas said that up to a fifth of the charity’s prisoner trainees could be released early. That meant they would leave jail without finishing industry-recognised qualifications crucial to landing their first job.

“Guys and girls are unsettled and they don’t know what is going to happen,” said Ms Thomas.

“People have to leave prison with a qualification for work - the whole basis of rehabilitation has to be rooted in employability.”

Sian Williams, CEO of Switchback, a charity that helps young men find a way out of the justice system, told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme that the only way to get the prison population down and solve the crisis is to reduce reoffending and recall to prison.

For that to happen, housing needs to be organised for people leaving prison “not just for six weeks, but for at least 3 months,” Ms Williams said, as well as access to benefits provided from day one and a sponsor to support them through the “very difficult transition back to society”.

A key challenge for officials working on the scheme is ensuring that any homeless ex-offender has somewhere to go if they are released. A government scheme aims to guarantee up to 84 nights’ accommodation for anyone in this situation - but in practice some offenders end up on the streets.

Charlie Taylor, the chief inspector of prisons in England and Wales, told the BBC his “biggest concern initially" was where people were "going to stay that first night”, warning a surge in cases of homelessness was likely.

The release of 1,750 prisoners on Tuesday, in addition to the roughly 1,000 people let out weekly, has put already stretched prison services under “extraordinary pressure” to ensure prisoners are ready to leave, Mr Taylor said.

It is "inevitable" that if people do not have support and stable housing they risk reoffending or breaching their licence conditions “and end up inside again anyway”, he added.

Mr Taylor's comments followed the publication of his annual report on the state of prisons, in which he detailed a "fragile, overcrowded" system and his "alarm" at the prevalence of violence and drug use behind bars.

Mark Fairhurst of the Prison Officers Association said the early release plan would create “breathing space” in overcrowded jails - but not without risks.

“We have had six weeks to prepare - and probation are overworked and under-staffed,” he said.

“But I think there has been enough liaison between all partner agencies.

“The issue is whether are there enough bed spaces for everybody for secure accommodation.

“There are no guarantees when we release anyone that they won’t reoffend.”

The Ministry of Justice is aiming to recruit 1,000 more probation officers by next spring to help manage the increasing number of ex-offenders in the community.

Officials project the 40% release scheme will cut spending on prisons by £200m a year - and rehabilitation advocates say that cash must be diverted into proven resettlement programmes.