'My parents translate for me during family calls'

Bilal Ahmady says he understands several languages and is learning more Farsi

- Published

Bilal Ahmady laughs as he explains why his family's weekly video calls around the world are so challenging.

They involve sitting around a dinner table in Leicester, speaking to relatives who cannot understand him.

The 18-year-old was born in the city and grew up speaking English, but his mum and dad are from Afghanistan and his grandparents, who still live there, speak Farsi.

Bilal says he understands several languages, but his parents often have to translate for him as he struggles to chip in.

"I get confused and I don't know what to say, and my mum and dad say 'no it's this word, no it's that word' and I just say it all wrong most of the time," he says.

Bilal visiting Afghanistan as a child with relatives who have now emigrated

Bilal has just begun a biomedical sciences degree at Keele University and is a Manchester United supporter.

His dad settled in Leicester after fleeing Afghanistan as a refugee almost 30 years ago and now manages a pizza takeaway in the city. Bilal says his mum came later, when his parents married.

During the family's weekly video chats, which are also joined by relatives in Italy, Russia, Canada and the US, Bilal says he often mixes up Farsi and English.

"I say 'I'm sorry I'm trying my hardest' and they laugh and they mock it but I'm learning slowly," he adds.

"There's very technical terms I don't understand. And some of the cities in Afghanistan I can't pronounce because it's so hard, so I just give up most of the time."

'Sign of respect'

Ferishta Bakhtari-Boodoo says many families face the same challenge and she is trying to help children growing up in similar circumstances to break through that language barrier.

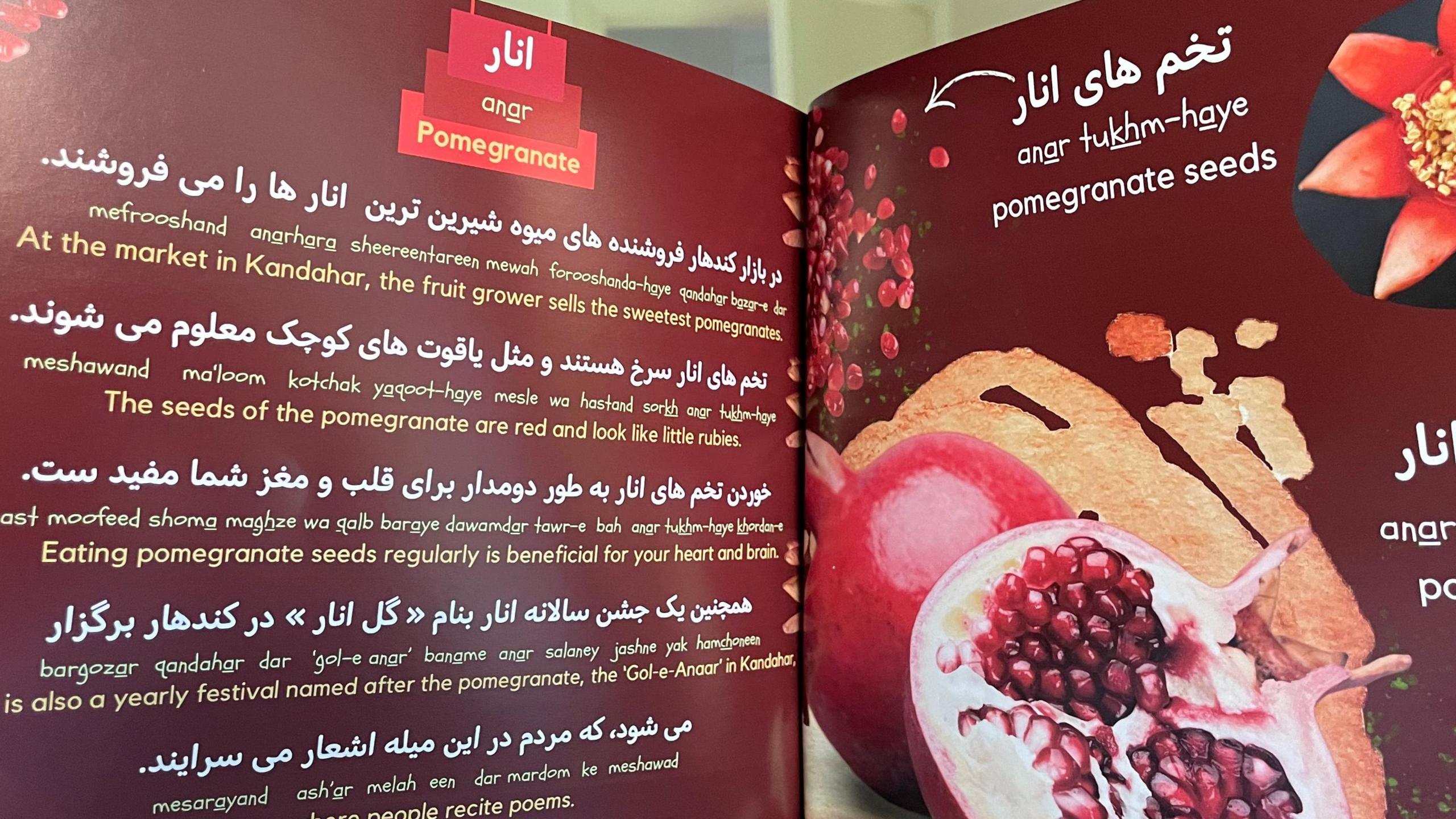

She has published a book - Our Fruits - which uses pictures and simple phrases in both English and Dari, the Afghan dialect of Farsi, to help them talk about produce from Afghanistan.

Ferishta says conversations can be difficult because children often lose touch with their parents' language as soon as they go to school.

"To have the heritage language is a sign of respect and love for the grandparent," she explains.

"You want to have deep conversations with your family members, you want a conversation and the kid does not speak the language."

Ferishta Bakhtari-Boodoo hopes her children's book will help unite families

Speaking at her book launch at Leicester's Central Library, Ferishta says children sometimes resort to using their hands and feet to help relatives understand them.

She hopes the book can also help families bond and teach British-born children about their roots.

"As you grow older, you feel a bit more appreciation for your own background, your culture, and you want to know where [you] would actually have lived if there wouldn't have been a war," says Ferishta.

"I wanted to talk about something positive, something about nature, flora and fauna, a nicer connection than what you read in the headlines.

"I just want to have a book for my daughter and all my nieces and cousins, which speaks about the beautiful side of Afghanistan."

Ferishta's book teaches simple phrases in English and Persian Dari

Bilal says he does try to learn new words in Farsi, but speaks a "slang version" that his relatives do not understand.

"Some of my friends have gone to courses to study their own home language," he adds.

Weekend classes in the city range from Gujarati to Ukrainian and Mandarin, with some also teaching children about their families' traditional culture.

One example is the city's Polish Saturday School, which runs lessons for children aged four to 13, as well as some GCSE and A-level classes.

Sławomira Małgorzata Wiśniewska and Patrycja Filipowicz run classes at Leicester's Polish Saturday School

Sławomira Małgorzata Wiśniewska, the school's director, says pupils often have one English and one Polish parent.

"It's very important because your language is your roots, and you never know what will happen in the future," she says.

Teacher Patrycja Filipowicz, who has been in the UK for 20 years, says the children also learn about Polish traditions and rituals.

"It's important for a sense of belonging - super, super important," she adds.

"It's part of your identity. If you go to Poland, you can feel that connection."

For Bilal, he thinks the language barrier has helped his family to grow closer despite living across different continents.

"It strengthens our relationship, because it's a joke and it keeps the humour going," he says.

"There's this little comedy joke that there's always a struggle and they always find it funny.

"I feel like they give lots of respect for someone who's learned a lot of languages rather than one."

Get in touch

Tell us which stories we should cover in Leicester

Follow BBC Leicester on Facebook, external, on X, external, or on Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external or via WhatsApp, external on 0808 100 2210.