Ban fossil fuel ads to save climate, says UN chief

- Published

The world's fossil fuel industries should be banned from advertising to help save the world from climate change, the head of the United Nations said on Wednesday.

UN Secretary General António Guterres called coal, oil and gas corporations the “godfathers of climate chaos” who had distorted the truth and deceived the public for decades.

Just as tobacco advertising was banned because of the threat to health, the same should now apply to fossil fuels, he said.

His remarks were his most damning condemnation yet of the industries responsible for the bulk of global warming. They came as new studies showed the rate of warming is increasing and that global heat records have continued to tumble.

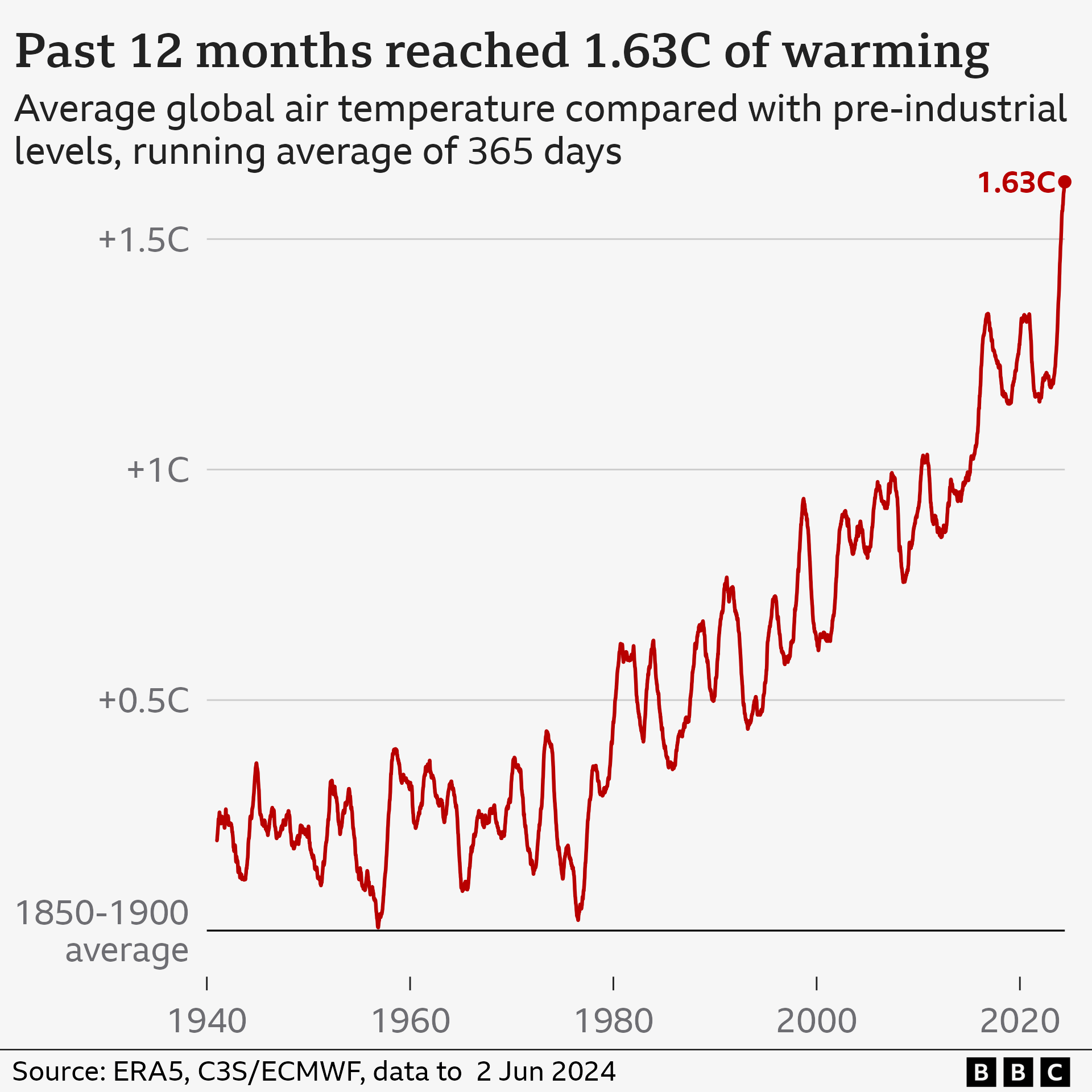

Data from the EU's climate service confirms that each of the past 12 months set a new global temperature record for the time of year. The high temperatures were driven by human-caused climate change, although they were also given a small boost by the El Niño climate phenomenon.

While a fading El Niño should soon bring a pause to the record-breaking sequence of months, temperatures will continue to rise in the long-term due to emissions of planet-warming gases from human activities.

Last year was the hottest on record and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) said on Wednesday that the record could fall again as soon as this year.

A group of around 50 leading scientists separately reported that the rate of global warming caused by humans has continued to increase.

They found that ongoing high emissions of warming gases mean the world is moving closer to breaching the symbolic 1.5C warming mark on a longer-term basis.

To try to avert this outcome, the UN Secretary General has called for more rapid political action on climate change, and a “clampdown” on the fossil fuel industry.

“We must directly confront those in the fossil fuel industry who have shown relentless zeal for obstructing progress – over decades.”

He said many in the oil, gas and coal industries had “shamelessly greenwashed” with lobbying, legal action and massive advertising campaigns.

“I urge every country to ban advertising from fossil fuel companies,” he told an audience in New York.

“And I urge news media and tech companies to stop taking fossil fuel advertising.”

In response, representatives of fossil fuel groups said they were committed to reducing their emissions.

“Our industry is focused on continuing to produce affordable, reliable energy while tackling the climate challenge, and any allegations to the contrary are false,” said Megan Bloomgren, Senior Vice President of Communications at the American Petroleum Foundation.

UN Secretary General António Guterres has long been a critic of fossil fuel use, and is now calling for global ban on advertising by coal, oil and gas producers.

The UK Advertising Standards Authority has previously pledged to clamp down on misleading environmental claims, while the European Union recently announced a new law to tackle the problem, external.

Mr Guterres' call for an outright ban on all fossil fuel advertising goes further - but it has no legal standing, and the UN has no means of enforcing the idea.

However, it will be seen as a boost for campaigners who have fought against sponsorship and advertising from coal, oil and gas companies.

Both the Hay and Edinburgh book festivals have recently suspended sponsorship from investment company Baillie Gifford following controversy over links to fossil fuel firms.

Sport is one of the biggest areas of fossil fuel advertising and sponsorship, with football having a long association with oil and gas producers.

Concerns over human health have seen alcohol and tobacco sponsorship banned in football in the past, and green campaigners will be hoping that the support of Mr Guterres will see fossil fuels go the same way.

In his address, Mr Guterres stressed that time was of the essence, with the impacts of rising temperatures already being felt - such as the recent deadly heatwaves in Asia or the floods in South America.

Deadly floods hit Brazil last month, and scientists at the World Weather Attribution group said the heavy rain was made at least twice as likely by climate change

The record-breaking global heat means that average temperatures over the past 12 months have been 1.63C above "pre-industrial levels" of the late 1800s, according to Copernicus data.

"We are living in unprecedented times," says Carlo Buontempo, director of Copernicus.

This does not constitute a breach of the Paris climate agreement, in which nearly 200 countries pledged to try to keep temperature rises below 1.5C, in order to try to avoid some of the worst impacts of climate change.

That is because the Paris agreement is generally understood to mean a 20-year average - to smooth out natural variability. Taken as a whole, the past decade was about 1.2C warmer than pre-industrial levels.

But a new study released today, external by a group of leading climate scientists highlighted how close the world is getting to a long-term breach of the 1.5C mark.

They estimate that from the start of 2024 the world could only emit around 200 billion more tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) for a 50/50 chance of keeping warming to 1.5C - down from 500 billion tonnes at the beginning of 2020.

At current rates of emissions, this "carbon budget" could be exhausted by 2029 - although the world would probably not pass the long-term 1.5C mark until a few years later, because of warming effects from greenhouse gases other than CO2.

There are uncertainties about how exactly the climate system will react to these factors, and of course whether countries make urgent cuts to emissions.

"We have a bit of control over this as a society," says lead author Prof Piers Forster, director of the Priestley Centre for Climate Futures at the University of Leeds.

Despite the gloom, there has been some recent progress, with particularly rapid growth in renewable wind and solar electricity.

Greenhouse gas emissions are also showing signs of plateauing - but they are still at record highs.

They need to fall quickly if global targets have a chance of being met, with every fraction of a degree of warming worsening climate impacts.

"Every degree matters; every tenth of a degree matters," says Ko Barrett, WMO Deputy Secretary General.

"The difference between 1.5C and say 2C could mean [...] dire consequences, for coastal communities, for fragile ecosystems, and the biodiversity that is contained within them, and for glaciers and the frozen parts of the world."