GPs at 'breaking point' say they must cap appointments - but could it harm patients?

Dr Tom Gorman says GPs are doing extra work that they are not paid to do

- Published

GPs in England have launched a work-to-rule action in a dispute with the government over what they say is a lack of funding. It threatens to bring chaos to the system.

The British Medical Association (BMA) announced the action earlier this month, and surgeries are now taking a variety of steps, with some limiting the number of patients each GP can see to 25 per day. That could reduce the number of available appointments by a third.

But with many patients already finding it difficult to get to see a doctor, there's increasing concern it could put patients at risk.

'Breaking point'

Dr Tom Gorman says taking part in the work-to-rule is a last resort, but he feels compelled to do it to protect his patients.

The 41-year-old has been a GP for eight years and says the system is at “breaking point”.

“We can't deliver for our patients. They’re struggling to get appointments. We don't want to take action but we’re being forced to protect our patients and staff.”

There is plenty of data to support such claims.

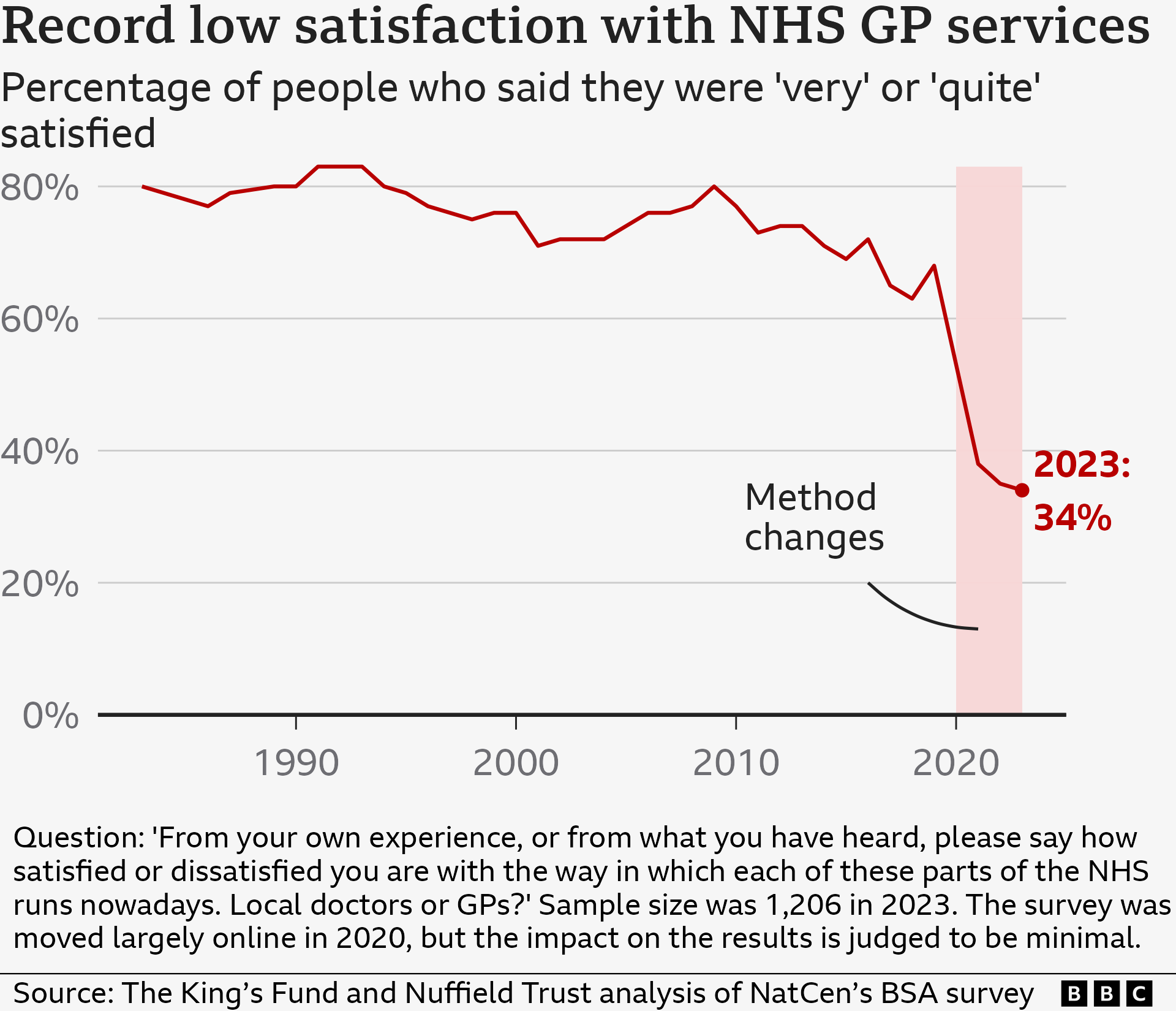

The most recent British Social Attitudes Survey, external – the gold standard measure of public attitudes towards the NHS – shows satisfaction with GPs has hit an all-time low.

Additionally, NHS England polling data, external suggests one in three people feel they have to wait too long for an appointment, while one in five describe their experience of contacting their GP as poor.

Younger adults and those from the poorest areas are the least happy.

The range of work-to-rule options

As a partner in a practice in Newcastle, Dr Gorman is in charge of deciding what action to take next.

That is because GPs are effectively independent businesses – so this is not a strike or campaign of industrial action in the traditional sense.

The British Medical Association (BMA) has suggested GPs can pick-and-choose from a range of options.

These include capping the number of patients that are seen each day, not doing tests and check-ups for hospitals, ignoring rationing guidelines which could result in a deluge of referrals for hospital care, and refusing data-sharing requests.

Dr Gorman says he and the other partners are yet to decide exactly what steps they will introduce but they certainly plan to take part.

“We're focusing action on stopping the immense amount of work that we are not contracted or paid to do - or that is unsafe to do.”

GPs believe that this focus means work-to-rule will not put them in breach of their contract under which they provide NHS services and, therefore, they should avoid having their funding docked.

Dr Gorman gives the example of taking bloods and other tests on behalf of hospitals to make the point.

“It's more convenient for patients but we often don't get paid for this," he says.

"We're essentially doing our job and the hospital's."

Dr Samira Masoud, a GP in Kent, agrees. She has spent time in recent years working as a locum, allowing her to pick and choose her hours, because the pressures of the job became too much.

“We are expected to see too many patients, working long hours into the evening and rushing appointments. It’s not safe and risks burnout.

“I was seeing 35 to 40 patients a day and you simply cannot give them the time they need. Capping patient numbers could make things much better for the GP and patient.”

Concern patients may lose out

Of course, placing restrictions on numbers has a knock-on effect – it makes it more difficult for all the patients who want to see a GP to get an appointment.

NHS England has warned this work-to-rule action could push more people into seeking help from A&Es as well as having a wider impact on the system, such as delaying discharges from hospital.

And patient watchdog Healthwatch England believes this could ultimately harm patients.

“GP access is the most common issue we hear about," says chief executive Louise Ansari.

“We’re worried the work-to-rule could make problems worse or even deter people from seeking help altogether.

"Any delay to care can have a huge impact on people’s physical and mental health.”

GPs to start capping appointments in work-to-rule

- Published1 August 2024

Even some GPs seem to share that concern.

A snapshot survey of more than 250 GPs by the medical publication Pulse released this week suggested one in four felt the work-to-rule could cause harm in the short term.

However, half said they would be prepared to continue indefinitely with the work-to-rule.

Much now depends on how many GPs take part.

The numbers involved since the BMA announced the work-to-rule at the start of August remain unclear.

It is unlikely every GP will get involved – after all only around two thirds are union members - and the BMA itself has said it expects it to be a “slow burn”, with GPs gradually ramping up the pressure.

How can this be resolved?

At the heart of the dispute is money. At the start of this year, the previous government announced funding for general practice would rise by just under 2%.

The BMA deemed that was not enough and called a ballot of members before the election was called.

The independent status of GP surgeries mean staff working for them are not directly employed by the NHS and so the pay awards of last year which prompted strike action by nurses and doctors were not the trigger.

The new government has already said it will put more money in, with Health Secretary Wes Streeting urging GPs to call off their work-to-rule.

Dr Becks Fisher, director of research and policy at the Nuffield Trust think-tank, believes it will take more than just a one-off boost to bring this to an end given funding has been "lagging behind demand and inflation" for years.

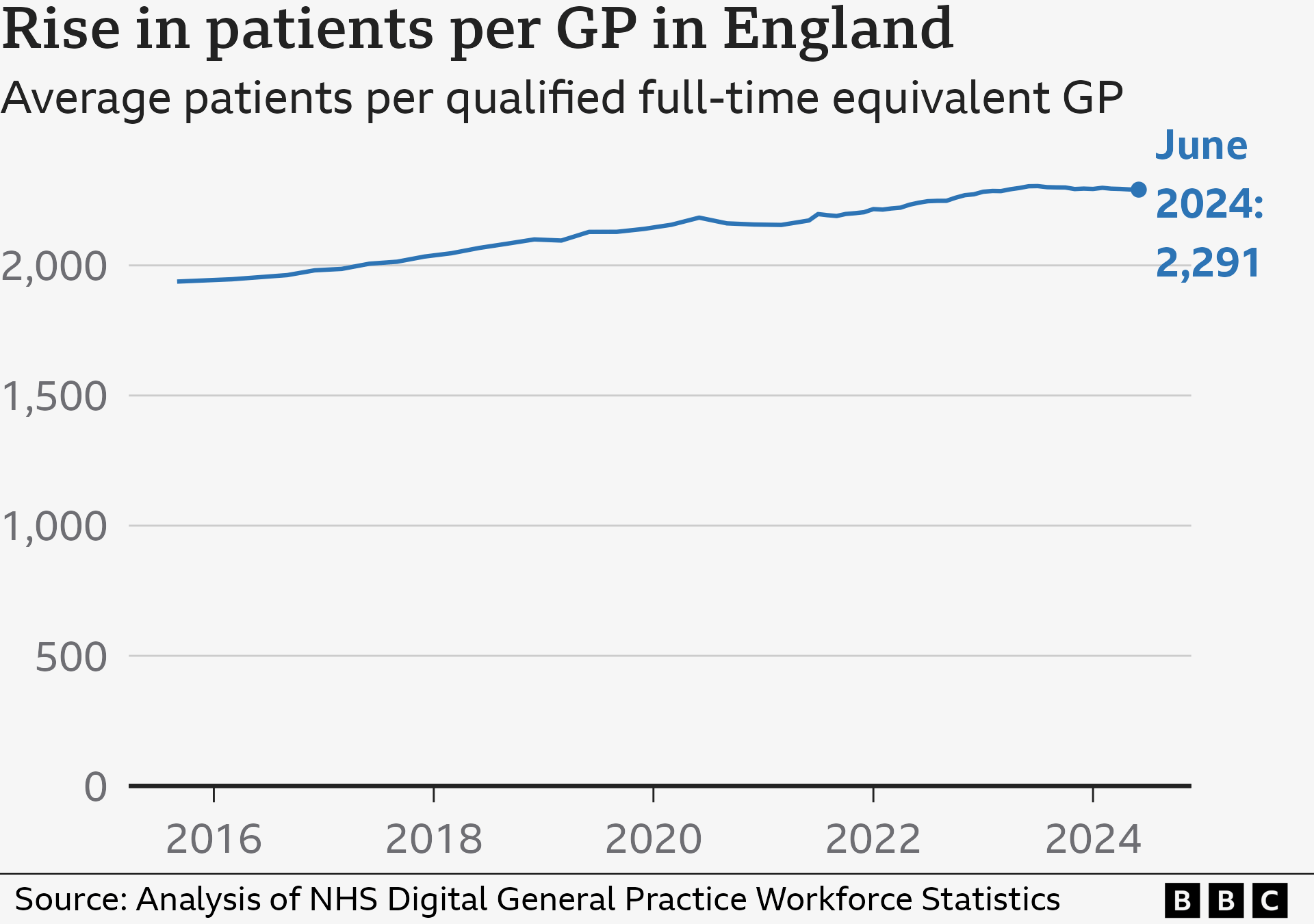

The result? A recruitment and retention crisis. Despite high-profile promises to increase the number of GPs during the last two parliaments, the Tories have failed to get anywhere near the targets they set.

It has meant the number of patients per GP has been rising and, crucially, the GPs most likely to walk away are those under the age of 30 – the very cohort on which the future of general practice depends.

Dr Fisher says until the sector is put on a more “stable foundation”, it is likely that this dispute will rumble on.

“GPs hate feeling that they aren’t able to provide the high-quality care that patients deserve,” she adds.

Research and data analysis by Hannah Karpel. Additional reporting by Kris Bramwell.

Related topics

- Published2 August 2024

- Published6 August 2024

- Published29 July 2024