'Green' ferry emits more CO2 than old diesel ship

Glen Sannox brings greater car capacity to the Arran route but a bigger carbon footprint

- Published

The carbon footprint of a long-delayed new "green" ferry will be far larger than the 31-year-old diesel ship that usually serves the route between the Scottish mainland and the island of Arran.

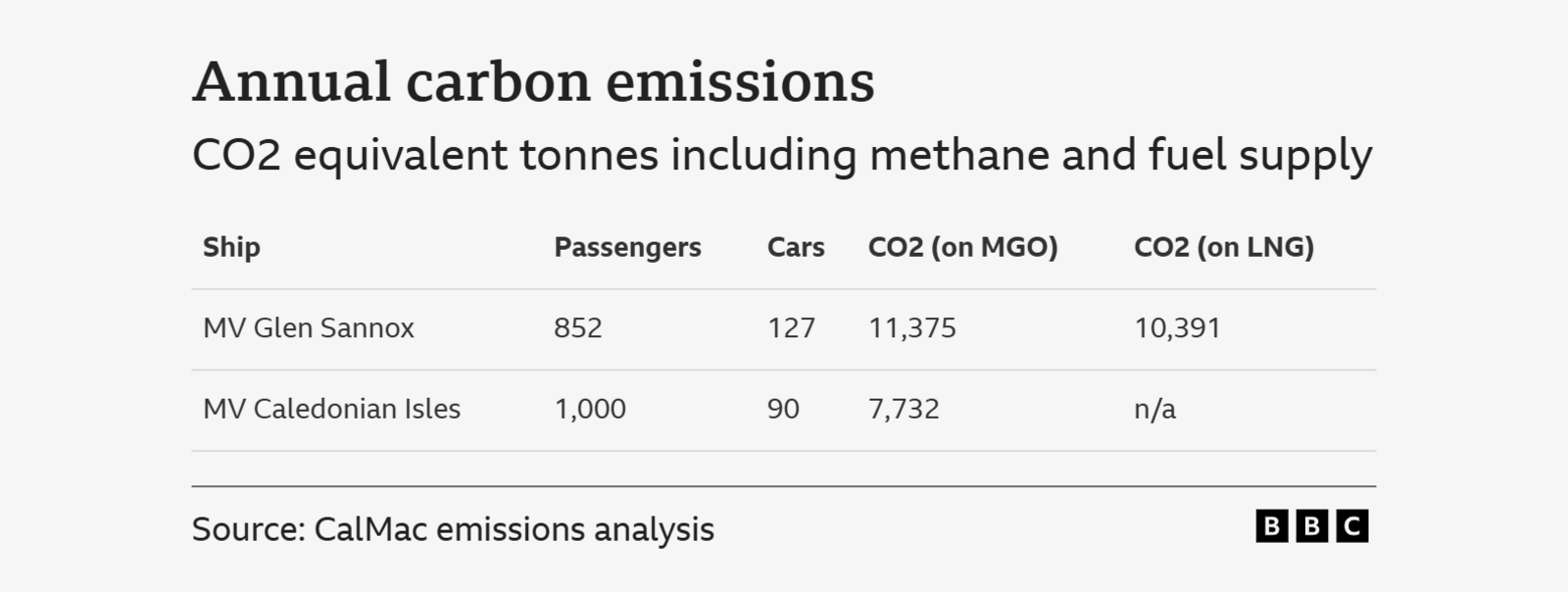

An emissions analysis by CalMac has calculated MV Glen Sannox will emit 10,391 equivalent tonnes of CO2 a year compared with 7,732 for MV Caledonian Isles.

The dual-fuel ferry has more car capacity but requires larger engines which also emit methane, a greenhouse gas with a far greater global warming effect than CO2.

Ferries procurement agency CMAL, which owns the ship, said the comparison was "inaccurate" as Glen Sannox is a larger vessel.

The size of Glen Sannox is a factor in its carbon footprint, but so too is the liquified natural gas (LNG) fuel which is less climate-friendly than previously claimed.

The business case for the ship, drawn up in 2014, predicted it would emit about 400 fewer tonnes of CO2 annually than existing vessels on the Arran route.

Instead it is now expected produce over 700 tonnes extra, rising to about 2,500 tonnes extra if methane is included in the calculation.

One expert on transport emissions told BBC News that if the "upstream" carbon cost of importing LNG from Qatar is included in the emissions calculation, it might be better to run the new ship on diesel.

Prof Tristan Smith, from University College London's Energy Institute, said: "In a best case scenario there's a negligible benefit of using LNG, and at worst there would be a deterioration."

Why was Glen Sannox so hard to build?

- Published13 January

Were Scotland's new gas-powered ferries a bad choice?

- Published20 April 2024

Glen Sannox is the first ferry ever built in the UK capable of running on both LNG and marine gas oil (MGO), a low-sulphur type of diesel.

At its launch in 2017, then first minister Nicola Sturgeon said it would contribute to "Scotland's world-leading climate change goals".

But the LNG technology also added complexity. The Ferguson shipyard had to overcome many engineering and regulatory challenges before the ship was delivered last month, years late and over budget.

The size of the ship also means it cannot berth at the usual mainland harbour at Ardrossan until a major redevelopment takes place.

When it enters service next month, Glen Sannox will bring a significant increase in car capacity. It can carry 127 cars compared to about 90 for Caledonian Isles.

Air pollutants, known as NOx and SOx, will be also reduced, while its power and manoeuvrability should mean fewer weather-related cancellations.

But in terms of greenhouse emissions, the CalMac analysis - seen by BBC News - reveals the benefits of the LNG technology are quite small.

Once methane emissions are factored in, the benefit of running the ship on LNG rather than MGO-only is less than 9%.

And the increased fuel consumption of the heavier ship means its overall carbon footprint is about 35% larger than Caledonian Isles, which is due to return to the Arran route in March following repairs.

Why is the ship's carbon footprint so big?

The carbon emissions have nothing to do with the design and construction of Glen Sannox by the Ferguson shipyard - the yard simply built the ship it was asked for.

Instead they are due to decisions taken by ferries procurement agency CMAL, ferry operator CalMac and Transport Scotland before the contract was put out to tender.

The old ferry, Caledonian Isles, was designed to carry 110 cars, but modern cars are so much wider, it can now only fit about 90.

The former main Arran vessel Caledonian Isles will operate alongside Glen Sannox until the second LNG vessel Glen Rosa comes into service

Glen Sannox was specified to carry 127 modern cars, or 16 HGVs, and to have a higher top speed (although this is not necessary for Arran sailings) resulting in a far heavier ship which requires bigger engines.

When running on LNG, CO2 emissions are up to 25% lower - but this is almost entirely offset by the larger engine size and higher fuel consumption.

A second reason is methane.

The LNG fuel mostly consists of methane, a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential (GWP) 28 times more potent than CO2 over a 100-year time span.

A small proportion of methane always passes through the engines unburnt, and is released up the funnels - something known as "methane slip".

CalMac has calculated that methane slip adds the equivalent of more than 1,800 tonnes of CO2 per year. This was not considered in the business case for the ships.

Glen Sannox has a huge cryogenic fuel tank in the centre of the ship which stores the LNG at minus 162C

There is also no local supply of LNG in Scotland, so the gas has to be brought up from a terminal in Kent using diesel road tankers.

This 445-mile road journey adds the equivalent of 140 tonnes of CO2 per year, compared to 19 tonnes for transporting MGO.

Ferries procurement agency CMAL, which owns Glen Sannox and its sister ship Glen Rosa, began proposing LNG as a lower emissions ferry fuel as long ago as 2012.

In a statement it said LNG was considered "the best option" at the time, and was always intended as a "transition fuel".

A CMAL spokesperson added: "Due to the difference in vessel size, propulsion power and expected sailing time, it is inaccurate to draw direct comparisons between the emissions of older vessels and MV Glen Sannox.

"The latter is a much newer vessel which is bigger and more powerful than the former, reflecting increased demand on ferry services."

Ferry operator CalMac said passenger and vehicle numbers on the Arran route had increased significantly over the past 30 years.

"More power is needed for the size of the vessel that can meet that demand, particularly carrying cars, and it should offer greater resilience against adverse weather," a spokesperson said.

"As a first in class vessel, we will learn more and more about MV Glen Sannox and her fuel consumption as we sail her."

Would it be better to run the ship on diesel?

CalMac's emissions analysis, carried out at the start of the year at the request of Scottish ministers, almost certainly underestimates the ship's carbon footprint.

The figures are based on ideal engine running conditions which minimise methane slip - and CalMac acknowledges that in real-life operations, emissions are likely to be higher.

The analysis also does not factor in so-called "blowdown" emissions of methane which occur every time the ship switches from LNG to running on MGO.

Any methane left in the engine crankcase and fuel lines is automatically flushed into the atmosphere - and CalMac has yet to establish how much will be released.

The report also only considers the carbon cost of transporting fuel from the LNG terminal in Kent - no allowance is made for "upstream emissions" involved in extracting the gas in Qatar and transporting it to the UK.

CalMac argues this is reasonable as it has no control over where the fuel is sourced.

But environmentalists and some academics argue that a fuller "well to wake" comparison of fuels would give a more realistic picture of the climate impacts.

"Upstream emissions are really important - especially if you are importing gas from Qatar or the US," said Prof Smith.

"The point of whether the upstream should or shouldn't be included is irrelevant – it's rearranging deck chairs on the deck of the Titanic at a point when we should be going to zero emissions."

How can Scotland's ferries become greener?

It is possible to run Glen Sannox on biogas, which is produced from organic waste such as manure or by-products from the whisky industry.

Since the carbon dioxide released when burning bio-methane originates in the atmosphere rather than underground, it is considered carbon neutral.

However, building a suitable plant in Scotland would require major capital investment and would also involve facilities for supercooling the gas to turn it into a liquid.

If a new biogas facility were to be developed, one option would be to repurpose the Grangemouth oil refinery where hundreds of jobs are currently under threat.

Four more large CalMac ferries under construction in Turkey will have conventional MGO engines with some limited battery power for manoeuvring in harbour.

But they have a deeper draught (the amount of hull below the waterline) and lower cargo requirements - meaning a more fuel-efficient hull shape has been possible.

CMAL says they have also been designed with the possibility of retrofitting them for potential future fuels such as ammonia.

An alternative option would be to consider catamarans, which are far more fuel-efficient than single-hulled ships.

The chartered catamaran Alfred, which can carry 98 cars and cost only £14.5m to build, has been operating successfully on the Arran route for the past 20 months.

Catamarans such as MV Alfred as generally more fuel-efficient than single-hulled ships

Its owner describes it as the most environmentally-friendly large ferry in Scotland because of its low fuel consumption.

CalMac believes advances in battery technology mean about 90% of its routes could potentially be serviced by all-electric ferries, rising to 100% if fast charging were available.

Prof Smith says this is the most climate-friendly option at the present time - although it would require significant upgrades to electricity infrastructure.

"Many other countries are putting battery electric vessels into routes similar to those serviced by these vessels," he said.

"And that's a solution which if charged with renewable electricity would be zero emissions at the point of operation.

"So it's a far more sustainable and viable investment in the long-run, and hopefully we will see more of those in the future."

- Published20 April 2024

- Published13 January

- Published20 December 2024