The school for pupils who reject the mainstream

Head teacher Alex Yates is in charge of 42 students aged five to 16

- Published

The number of pupils who refuse to go to school is growing as anxiety around school attendance increases.

At Konstam House, the Royal Free Hospital Children's School's new unit for pupils unable or unwilling to attend school, head teacher Alex Yates says he prefers the term "emotionally based school avoidance" - or EBSA - rather than "school refusal", as it is sometimes known.

"The children are trying to solve a problem, and the problem is that they can't manage in a mainstream setting," he said.

The number of children in London persistently missing more than 50% of school sessions rose from 6,586 in the 2018-19 academic year to 14,689 in 2022-23.

Last year more than 140,000 children in England were repeatedly absent from school in the spring term - nearly three times as many as before the pandemic, according to government statistics.

In Camden, schoolchildren persistently missing 10% or more of school sessions increased from 2,806 in 2018-19 to 4.296 in 2022-23.

The Konstam unit only admits children from the borough of Camden

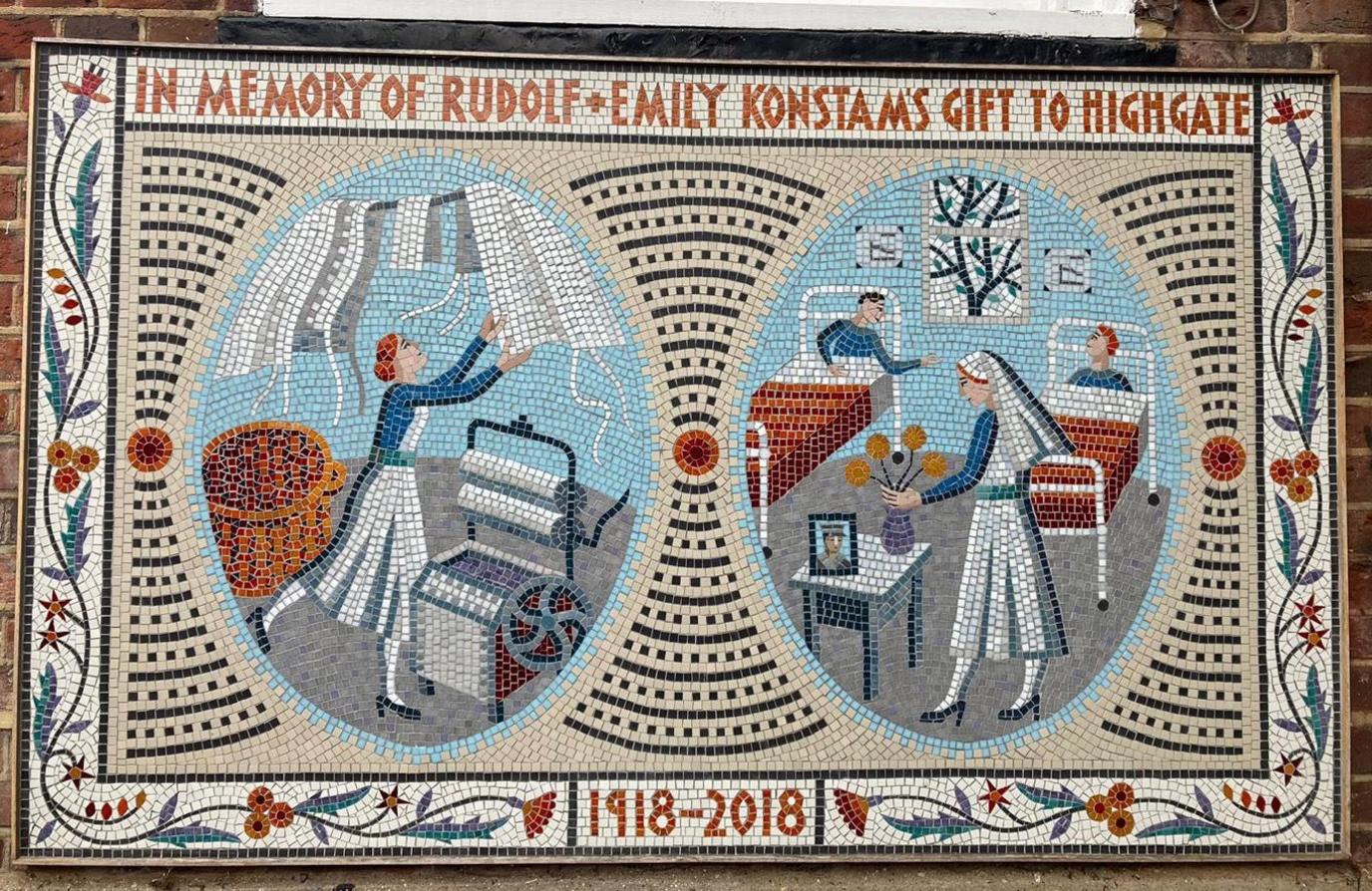

The Konstam unit, which opened in September, brings together the specialist knowledge and staff from across the three sites of the Royal Free Hospital, which opened as a children’s health clinic in 1924, funded by the Konstam family to commemorate two sons who were killed in World War One.

It only takes pupils from within the borough of Camden, but nonetheless has had many inquiries from parents from outside the borough who are desperate to get their child into the programme.

There are 42 students here, aged five to 16, who don't have conventional behavioural needs that might be dealt with in a pupil referral unit.

Mr Yates told BBC London: "The mission we have in Konstam is for children who otherwise wouldn't be able to access education at all because of high levels of anxiety, because of depression, sometimes because of much more serious things such as self-harm, and eating disorders.

"Once young people are with us, we've got a really strong ethos that they have to take responsibility as well," explains Mr Yates.

Jason Rose's younger son has missed two years of school

'Why my kids don't go to school'

Jason Rose from Bromley has two sons, aged 12 and 16, who are not eligible to attend the Konstam unit as they do not live in Camden. He said his younger boy had been out of school for more than two years and the older one for more than a year, both due to anxiety.

"To me the phrase 'school refuser’ implies a conscious decision not to go to school," he explains.

"Whereas for both my sons, it was very much the case that they were physically unable to attend school – it wasn’t a decision that they, or my wife and I, made.

"My youngest would literally pull his own hair out, barricade himself in a cloakroom and bang his head against a wall. He’d refuse to be in the same space as peers – he effectively had a self-imposed isolation.

"The school said, even when they were moving through the building and they’d walk near to his classroom, he would physically cower.

"I think the pandemic was potentially a contributing factor, but with both boys there were difficulties before; possibly it accelerated the issue. It’s very difficult to know."

The older boy has missed his GCSEs and is upset about that, Mr Rose said.

"To some extent he blames my wife and I for him not being in school. With my youngest son, he’s quite happy being at home but he’s missed two years not at school, plus all the time before when he struggled to participate – his education, and therefore his future, has been hugely negatively impacted," Mr Rose explains.

Mr Rose's wife with the couple's younger son

Konstam House uses equine therapy, art and music to try to ready pupils to return to formal education, as well as some remote learning and small classroom groups. Some pupils will move through the different educational settings of the unit and might stay for months or even longer.

At the heart of the matter is mental health, which is something that deteriorated for many young people during the pandemic lockdowns.

"We can't deny that Covid has had an impact," says educational psychologist Dr Cat Halligan. "For young people who are just on the edge of being able to manage in school, lockdown enabled that avoidance. The more they are away, the more difficult it is to get back into it again."

The philosophy of staff at Konstam House is that all behaviour is a form of communication, and that young people need understanding. The pupils sign an agreement centred on "co-operation, consideration, contribution" aimed at enabling them to buy into the idea of their own recovery.

"Early intervention is really important," says Dr Halligan. "The earlier we intervene, the more likely we are to prevent those difficulties from becoming entrenched. Noticing those patterns, and getting your child's school involved, is really, really important."

Originally the institution was a health clinic

In one small classroom, an online lesson called Linked Up is taking place. It's for students who don't even feel able to leave their homes.

Eight young people are being given breathing exercises to do over Zoom by a drama teacher, watched over by the unit's safeguarding lead, Gemma. She is also the Royal Free Hospital's specialist teacher on the paediatric ward, often working with children who have eating disorders.

In another classroom, steel pans, a keyboard and tambourine are laid out near some comfy beanbags, as therapist Margaret Moore takes a relaxed class for teenagers.

She says every year is different, but there is no doubt in her mind that the lockdowns during the pandemic set her students back.

"These are children who we've spent a long time encouraging back out into the world and then all of a sudden they're locked in again. When they come in, it's like the the world and its opportunities are lost to them - or they think its been lost.

"We try to reignite that passion to learn and to move forward and to have the same chances as their peer group back at mainstream school."

Margaret Moore has no doubt that the Covid lockdowns were damaging for children

Some children here will be reintegrated into mainstream education once they can cope again.

Staff are confident that many of the pupils will eventually go on to university, work or apprenticeships, as former students at the Royal Free Hospital's schools already have.

"Young people have to feel engaged again, they need to feel they belong, they have to have agency. We can't just do things to them," Mr Yates says.

"I think this is where some mainstream schools are having to think more carefully about their curriculum.

"Those old structures around hierarchy and conduct, they do feel like they are straining a bit."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

More on school avoidance

- Published6 September 2023

- Published15 September 2021

- Published26 June 2019