Prisoners and the Army donated infected blood in NI

Victims and families of the infected blood scandal stood outside Westminster on Sunday ahead of the inquiry findings

- Published

Sources of infected blood donations in Northern Ireland came from prisoners and the Army, an inquiry has found.

The Infected Blood Inquiry published its findings on Monday.

It found that the catalogue of separate failures, which caused thousands of people to be infected after receiving blood, were serious but taken altogether they amounted to "a calamity".

It also found that Northern Ireland brought “little observable influence” over the scandal and took most decisions from London, with “mirrored subservience” over the production and management of blood.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has apologised "wholeheartedly and unequivocally" for the failings made by leaders and medical professionals.

Compensation is expected to be announced in the coming days.

In August 2022, the government announced that 4,000 UK victims would receive interim payments of £100,000, including about 100 in Northern Ireland.

Speaking outside the inquiry, Health Minister Robin Swann apologised for the harm done in Northern Ireland by "this abhorrent scandal".

He said while this is a central government issue, he will urge his successor to ensure victims are supported and compensated.

"Everyone across the United Kingdom, no matter which one of the four nations they come from, must all be treated equally, because they were all failed equally," he said.

The inquiry has recommended a compensation scheme be set up immediately and a permanent memorial established in Northern Ireland.

It further recommended that Northern Ireland medical and dental training agencies take steps to ensure lessons are learned and a statutory duty of candour is introduced and extended to cover health leaders.

How did the scandal affect Northern Ireland?

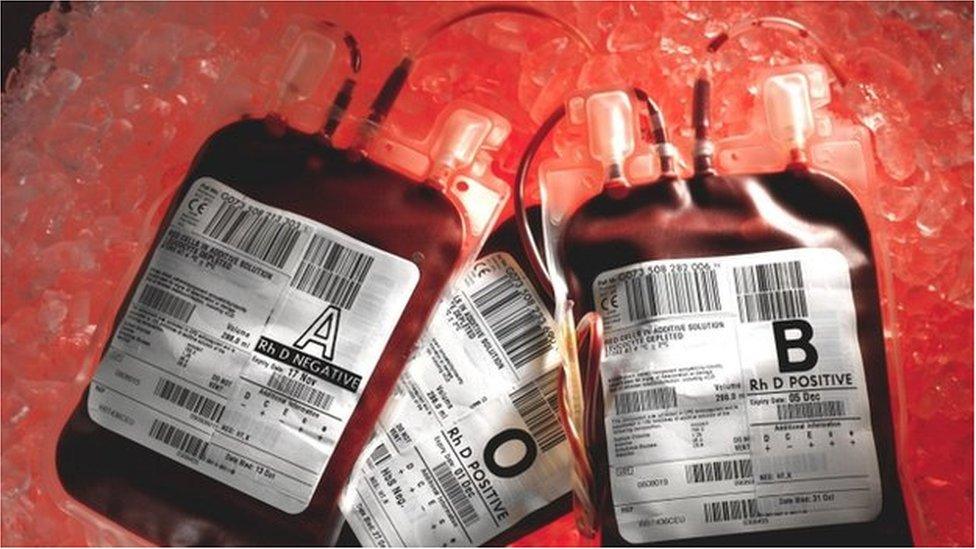

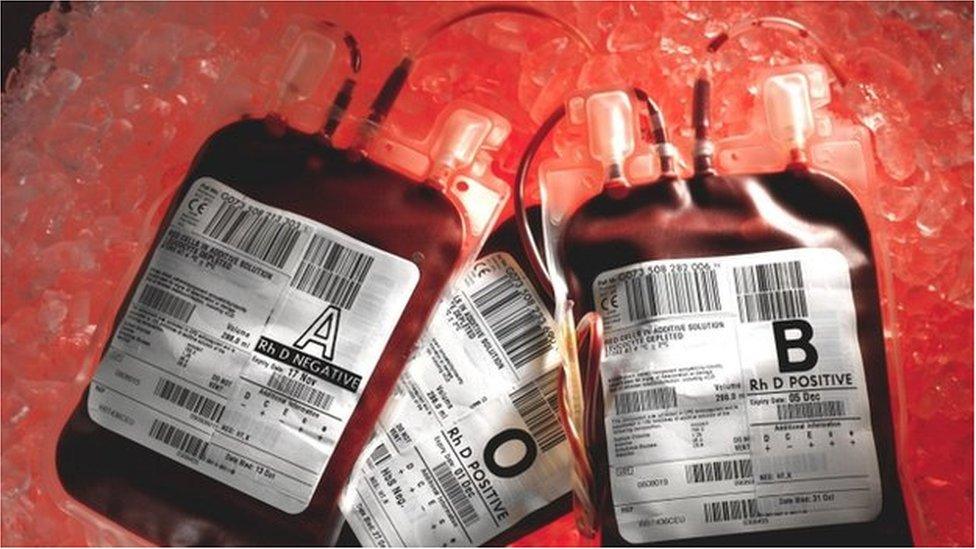

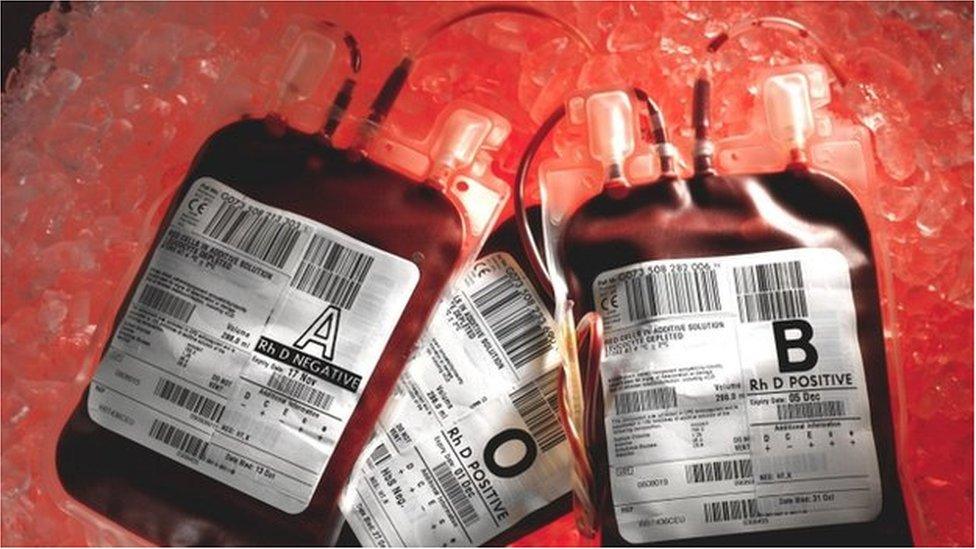

More than 30,000 people across the UK, including Northern Ireland, were infected with HIV and hepatitis C between 1970 and 1991 by contaminated blood products and transfusions.

It is said to be the worst treatment disaster in NHS history and the inquiry, which took evidence between 2019 and 2023, found that it largely could have been avoided.

Blood donations and donors were scarce in Northern Ireland during the 70s and 80s; out of all the nations and regions, Northern Ireland was the least self-sufficient.

As part of the overall supply of blood donations prisoners and members of the armed forces were involved.

Infected blood scandal victims betrayed by cover-up, inquiry says

- Published20 May 2024

NHS and government covered up infected blood scandal

- Published20 May 2024

Northern Ireland received “significant amounts” of blood from Army donors, due to their presence during the Troubles, which the inquiry said was “valuable” but there was a higher chance that blood would be infected with hepatitis B.

Prison donations took place across Northern Ireland but stopped in October 1983 as prisoners were considered “higher risk groups” likely to be infected.

However, the inquiry said those donations could and should have stopped earlier.

Victims and campaigners travelled to Central Hall in Westminster, London, for the publication of the inquiry report

The Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, one of five geographic trusts which oversees Northern Ireland's health services, said it offered "a heartfelt and sincere apology to everyone who either directly or indirectly continued to suffer" due to events outlined in the inquiry.

"We recognise the distress and grief felt by so many and we accept that no apology can reverse those events or bring back loved ones to families and friends who have been experiencing the most incredible sadness and loss for many decades," it said.

It added it will carefully consider the recommendations of the report.

The Northern Ireland Blood Transfusion Service (NIBTS) also apologised, saying it acknowledged the "fortitude, dignity and perseverance conveyed by the infected and affected".

It said it will "explore how we can adopt the inquiry's recommendations to deliver improved and enhanced care".

Infected blood inquiry: Victims react to report into 'abhorrent scandal'

Many not here to see long-delayed justice

by Marie-Louise Connolly, BBC News NI health correspondent

Another public inquiry and once again its findings reveal a scandal that could have been largely avoided.

It points towards another cover-up, accusing successive governments and the health service of trying to conceal what happened.

The pain of patients was compounded by those in leadership refusing to accept that wrong had been done.

Warnings and recommendations were ignored - as a result thousands of innocent patients died.

Basics around patient safety and recommendations on the screening of blood products from paid prisoners and drug dealers were ignored.

While the truth is finally out, yet again another public inquiry and its findings has been thrust on the public and the Northern Ireland Assembly.

A recommendation from today that a duty of candour be introduced echoes similar calls made in the 2018 hyponatraemia inquiry.

While justice has been delivered - sadly so many aren't here today to see it.

Conan McIlwrath says there needs to be a "firm" government response to the report

Blood inquiry report 'is quite damning'

Conan McIlwrath, from Larne, County Antrim, was born with haemophilia but contracted hepatitis C stage one from contaminated blood given to him as a child.

He is among those who travelled to London to hear the findings being delivered.

He said there was some "harsh and damaging language" in the report.

"The government needs to respond quickly and firmly - there’s more behind these words in the report - you don’t use the word failure 190 times for nothing."

Paul Kirkpatrick, from Londonderry, who has haemophilia, previously told the inquiry he had lived a life being told he was a public health risk and had been paranoid that his children would be affected.

As a result of the infection he contracted hepatitis B and C.

Over the past three decades, he said he had batted away various "clouds", including potential cancer, CJD, Aids, never knowing what the health service would throw at him next.

Speaking to BBC News NI in London, Mr Kirkpatrick said it has been a "very emotional and anxious day" as he listened to the "damning" report.

"It is what we expected after listening to the inquiry over the last number of years but it doesn’t make it any easier," he said.

"There was enough information out there to highlight this was an issue way before the 70s - there were opportunities to stop this."

Speaking at a press conference after the publication of the inquiry’s findings, Nigel Hamilton from Haemophilia Northern Ireland, who has the condition and contracted hepatitis C after receiving contaminated blood products, said a culture change is needed in Northern Ireland so this does not happen again.

“We have suffered in Northern Ireland and the production of this has been healing and supportive - it recognises the injustices."

He said the government had been "culpable of neglect and abandonment, and that has been a culture that has also been taken on in the health system".

Why did the infected blood scandal happen?

Two main groups of people caught up in the scandal were people with haemophilia and those with similar disorders; they have a rare genetic condition which means their blood does not clot properly.

In the 1970s the UK was struggling to meet the demand for blood-clotting treatments, so imported supplies from the US.

But much of the blood was bought from high-risk donors such as prison inmates and drug-users.

Factor VIII was made by pooling plasma from tens of thousands of donors.

If just one was carrying a virus, the entire batch could be contaminated.

After being given the infected treatments, about 1,250 people in the UK with bleeding disorders developed both HIV and hepatitis C, including 380 children.

Around two-thirds later died of Aids-related illnesses. Some unintentionally gave HIV to their partners.

Another 2,400 to 5,000 people developed hepatitis C on its own, which can cause cirrhosis and liver cancer.

UK blood donations were not routinely screened for hepatitis C until 1991, 18 months after the virus was first identified.

It is difficult to know the exact number of people infected with hepatitis C, partly because it can take decades for symptoms to appear.

Related topics

- Published20 May 2024

- Published20 May 2019

- Published17 August 2022

- Published27 January 2023