Can diplomacy bring Middle East ceasefire? Early signs don't bode well

- Published

After the US, the EU and 10 other counties called for an immediate ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah, the White House went into spin mode trying to build momentum for its proposal.

On a late night Zoom briefing so packed with reporters that some had to be turned away, senior Biden administration officials described the announcement as a “breakthrough”.

What they meant was they saw getting an agreement from key European countries and Arab states, led by Washington, as a big diplomatic achievement during the current explosive escalation

But this was world powers calling for a ceasefire - not a ceasefire itself.

The statement urges both Israel and Hezbollah to stop fighting now, using a 21-day truce, “to provide space” for further mediated talks. It then urges a diplomatic settlement consistent with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1701 - adopted to end the last Israel-Lebanon war of 2006, which was never properly implemented. It also calls for agreement on the stalled Gaza ceasefire deal.

Beyond the three-week truce, it packages up a series of already elusive regional objectives. Some have remained out of reach for diplomats for nearly two decades already.

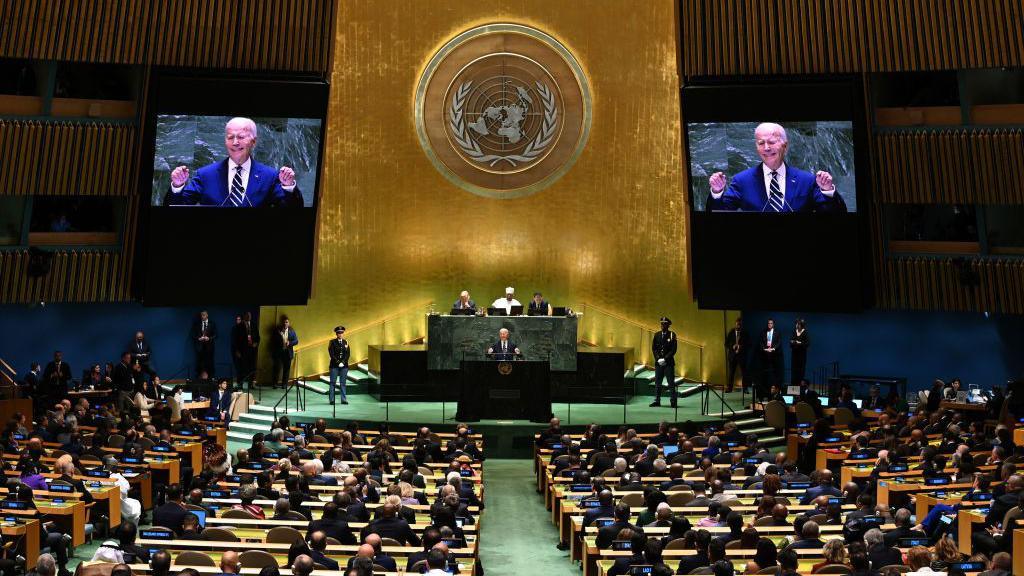

To issue the agreed upon text, the Americans had the advantage of world leaders gathered in New York for the annual United Nations General Assembly.

But what the “breakthrough” did not mean - as it has become abundantly clear on the ground - was that Israel and Hezbollah had reached an agreement.

Here, it seemed like US officials were trying to present the position of the two sides as more advanced than it really was - likely an attempt to build public momentum behind the plan and to pressure both sides.

Asked whether Israel and Hezbollah were onboard, one of the senior officials said: “I can share that we have had this conversation with the parties and felt this was the right moment based on the [ceasefire] call, based on our discussion - and they are familiar with the text… We'll let them speak to their actions of accepting the deal in the coming hours.”

Pressed again on whether this meant Israel and Hezbollah had signed on - especially given the fact that the US does not have direct contact with Hezbollah - the official clarified that the US had talked intensively about the text with Israeli officials and with Lebanon's government (meaning its officials would have contact with Hezbollah).

“Our expectation is when the government of Lebanon and when the government of Israel both accept this, this will carry and to be implemented as a ceasefire on both sides,” said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

That sounded pretty promising. But after the late-night call, the diplomats woke to news of more Israeli airstrikes on Lebanon, including in Beirut, and more Hezbollah rocket fire into Israel. This week has seen Lebanon’s bloodiest day since its civil war; Israeli airstrikes killed more than 600 people including 50 children, according to Lebanese health officials.

BBC reporter asks Trump what he would do differently on Middle East

Could a ceasefire plan work this time?

So how significant is the diplomacy, and can it actually lead to a ceasefire?

The early signs don’t bode well. The office of Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu, as he boarded a flight to New York for his UN speech on Friday, issued a defiant statement saying he hadn’t agreed to anything yet. It added that he ordered Israeli military to continue fighting with “full force”.

Lebanon’s prime minister Najib Mikati dismissed reports that he signed on to the proposed ceasefire, saying they were “entirely untrue”.

Instead, the joint statement creates a baseline position for the international community to try to exert pressure on Israel and Hezbollah to pull back and stop.

More work will be done in New York before the week is up. And it likely will continue afterwards.

It is significant that the Americans, leading the charge along with the French, have used the words “immediate ceasefire”. After 7 October, the US for months actively blocked resolutions from the UN Security Council calling for such a ceasefire in Gaza, until President Biden unexpectedly used the word and the US position shifted.

Since then, intensive diplomacy led by Washington has failed to reach a ceasefire and hostage release deal between Israel and Hamas, with the US currently blaming a lack of “political will” by Hamas and Israel. Meanwhile, the US has continued to arm Israel.

That doesn’t inspire confidence that Washington and its allies can now strong-arm Israel and Hezbollah into a quick truce, especially given the fighting on the ground, the intensity of Israel’s air strikes and last week’s explosive pager attacks on Hezbollah, which has continued to fire into Israel.

On the other hand, the difference between this and the Gaza ceasefire is that the Israel-Lebanon agreement doesn’t involve hostage negotiations, which contributed to the deadlock over a Gaza deal.

But the objectives for each side are still very significant. Israel wants to be able to return 60,000 displaced residents from the north and maintain security there free from Lebanon's daily rocket fire.

Hezbollah seeks to stop Israeli strikes on Lebanon where more than 90,000 people also are displaced from the south.

The Shia militant group will aim to maintain its dominance in the country and its presence in the south while trying to ensure the bloody events of the last week don’t invoke more internal resentment of the group amid Lebanon’s fractious sectarian divisions.

Finding agreement between these two sides has already evaded Amos Hochstein, Washington’s envoy on the Israel-Lebanon crisis, for months.

And here is where the US-led desire to get an immediate truce gets complicated.

My understanding of the negotiations to reach the joint statement is that Washington pushed to make sure it linked the 21-day ceasefire to creating the negotiating time for a longer-term settlement.

Namely, that the two sides negotiate to implement Resolution 1701, which implements multiple conditions on Israel and Hezbollah. These include the group’s retreat from a strip of Lebanon south of the Litani River and, in the long term, Hezbollah’s disarmament.

Ever since 2006, each side has long accused the other of breaking the terms of 1701.

All of this means that an objective, which has already evaded diplomats for nearly two decades, is now being wrapped into the short-term plan for calm between these two sides. As the missiles continue to fall, the current diplomacy is asking a lot.

Related topics

- Published24 September 2024

- Published24 September 2024