Footprints a reminder of childhood under occupation

Tony Hobbs said his grandfather had been amused by the two German soldiers' Yorkshire accents - picked up when they were prisoners after World War One

- Published

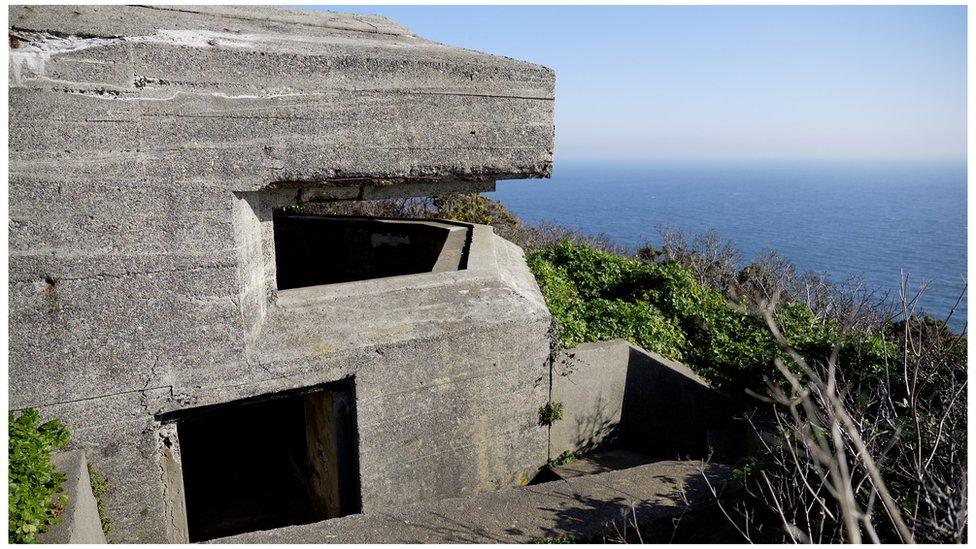

Bunkers are a visible reminder of the Channel Islands' Nazi Occupation and, at one coastal fortification, footprints of a small child set into the concrete are an islander's lasting link back to that time.

Tony Hobbs was three-and-a-half years old when German forces landed in Guernsey in June 1940.

Now 87, his memories of that time are still clear.

During the building of a coastal bunker, built on the island as part of Hitler's Atlantic Wall, he was taken to the top and left his footprints in the drying concrete.

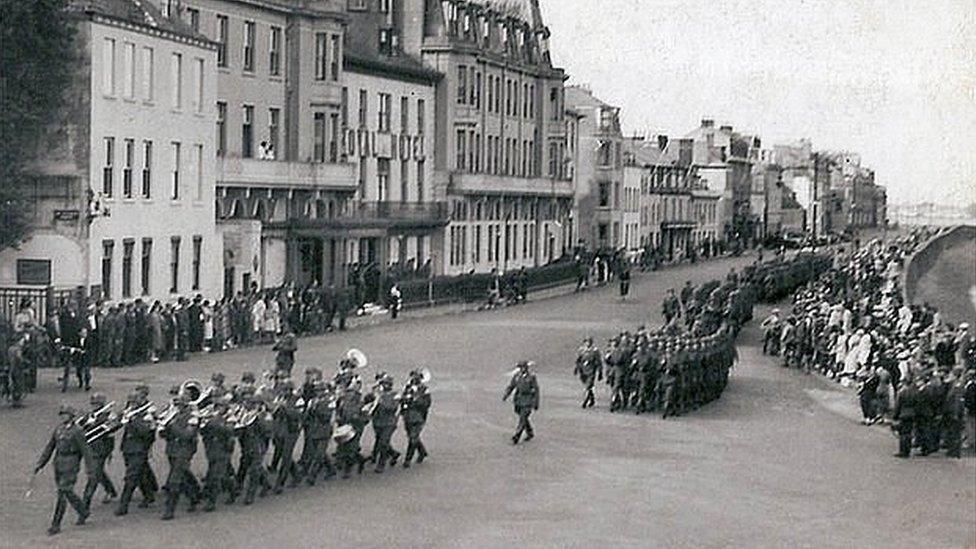

The Channel Islands were heavily fortified as part of Hitler's Atlantic Wall, a network of defences running from Norway to southern France

Two days before the start of five years of occupation, three German planes bombed St Peter Port Harbour as trucks were lined up on the quayside - the majority were carrying tomatoes for export.

Thirty-four people were killed and 33 were injured in the attack on 28 June 1940, which saw 49 vehicles damaged or destroyed.

Mr Hobbs remembers watching from his home at Salerie Corner, as the planes came in and bombed the trucks lined up at the White Rock and as horses fled without their riders, dragging their carts behind them.

Final goodbye

The next day he said what was to be his final goodbye to his father as he went off on the lifeboat.

Harold Hobbs was part of the Guernsey lifeboat crew that was tasked with collecting up the Jersey lifeboat to take it to England, because the authorities did not want it to fall into enemy hands.

As the lifeboat had been approaching Jersey, it was attacked by a German plane and Mr Hobbs senior was killed.

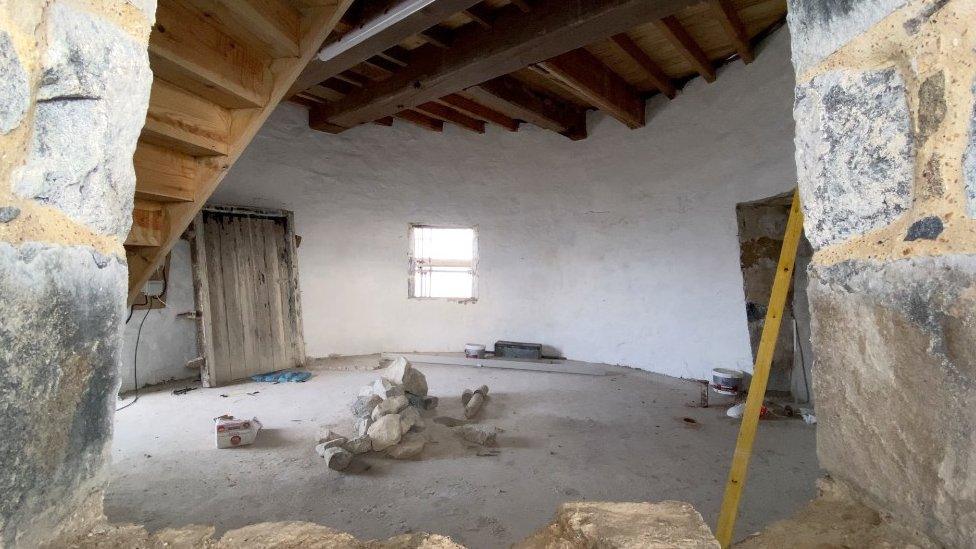

The footprints on the edge have worn away but others are still visible

After his father's death, Tony Hobbs, his mother and grandfather moved to take over an empty family house at L’Islet for the duration of the occupation.

The family had decided life might be safer in the countryside than in the main town of St Peter Port.

His mother took on the job of washing clothes for some of the German officers in return for food and his grandfather befriended some of the German soldiers.

Mr Hobbs said: "My grandfather had a bit of a laugh because they were speaking in a Yorkshire accent, and they told my grandfather that during the First World War they were captured in one of the first battles and spent the best part of four years up in Yorkshire.

"One day, they asked me if I’d like to go on top of the bunker. So, I climbed the ladder, and the bunker was just finished so I stood right on the very edge of it."

Tony Hobbs revisited the top of the bunker 60 years after he had left his footprints

With the concrete still drying, his feet left imprints.

Mr Hobbs said: "I remember going up on the ladder. My grandfather told me that they found a ladder from somewhere and they went up and stood beside me. I was only three inches from falling over the top."

It was some time before he went back up to see them again: "I kept saying for 60 years I’m going up there one day.

"And then one day I bought an old van and it had a roof rack and my wife said 'put your ladder on top'.

"So that’s what I did. I put the ladder on top and I went up and that was 20 years ago."

The bunker is currently owned by the Liberation Group and sits on the land alongside the Puffin and Oyster restaurant, overlooking Grand Havre Bay.

The view from the top

By BBC Guernsey communities reporter Isla Blatchford

I got permission from the bunker's owners to see if the footprints had survived the past 80-plus years. Tony joined the search from the ground via a video call.

I certainly didn’t have the confidence of a young Tony as I climbed up the ladder.

My knees were knocking as I stepped on to the roof. I was OK once I was up and the view certainly helped. There can’t be many people who have looked at Grand Havre from that vantage point.

My nerves - and the workplace risk assessment - didn’t let me get too close to the edge but I could see that the footprints Tony had said should be there, no longer were. The concrete had worn smooth.

But, further in, I spotted a little footprint, highlighted by the small amount of dirt filling it. Alongside it, there was another. Small enough to be a child’s. I was happy and relieved to show them to Tony again.

I’m privileged to have seen the mark he made on history and to have heard his stories of life during the occupation.

Follow BBC Guernsey on X (formerly Twitter), external and Facebook, external. Send your story ideas to channel.islands@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published6 March 2024

- Published4 March 2024

- Published29 January 2024

- Published17 February 2023

- Published6 May 2022

- Published10 March 2021