The real costs of China's anti-corruption crackdown

- Published

China has seen a decline in the sales of luxury goods since the drive to root out corruption began

Much has been written about China's ongoing crackdown on corruption, but now one of the world's biggest banks has put a price on it.

According to a report published by Bank of America Merrill Lynch this week, the Chinese government's anti-graft campaign could cost the economy more than $100bn this year alone.

That's a lot of economic activity, something not far off the total size of the economy of Bangladesh, which supports some 150 million people (although admittedly not very well).

Macro effects

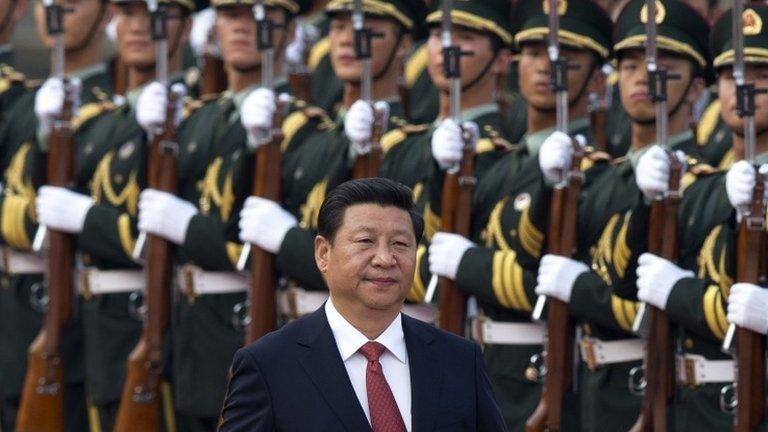

Many of the micro effects of Xi Jingping's anti-corruption drive have already been well documented of course; a slowdown in the restaurant trade for example, and a big dip in sales of luxury goods.

Over the past year or so, in Shanghai's posh malls and boutique designer shops - once at the centre of the happy merry-go-round of official largesse and gift giving - you've almost been able to hear the sound of the weeping and gnashing of teeth.

But the BofAML report suggests that the campaign is also having a significant and troubling macroeconomic effect.

Officials are reluctant to spend public money on projects fearing corruption allegations against them

Since early last year, it says, government bank deposits have been soaring, up almost 30% year on year.

Even honest officials, the report suggests, are now so terrified of starting new projects, for fear of being seen as corrupt, that they're simply keeping public funds in the bank.

The total cost to the economy of the prohibition on government consumption and the chill on administrative spending is an estimated reduction in growth of at least 0.6% this year.

But it could, the report argues, be as high as 1.5% which, by my rough calculation, gives us the figure of about $135bn of lost economic activity.

The report's authors admit their calculations are a "back-of-the-envelope estimate of fiscal contraction", but even if they are only half right it is an extraordinary amount of money and it highlights some of the challenges facing China's anti-corruption crusader-in-chief, President Xi Jinping.

Since taking office more than a year ago he has made the cause his defining goal, warning that official graft and extravagance threaten the very survival of the ruling Communist Party.

Sex trade

Earlier this week, an unconfirmed news report gave a tantalising glimpse of the seriousness of the project, claiming that the Chinese authorities had seized from the family and cronies of just one individual (Zhou Yongkang, the former powerful politburo member) assets worth more than $14bn.

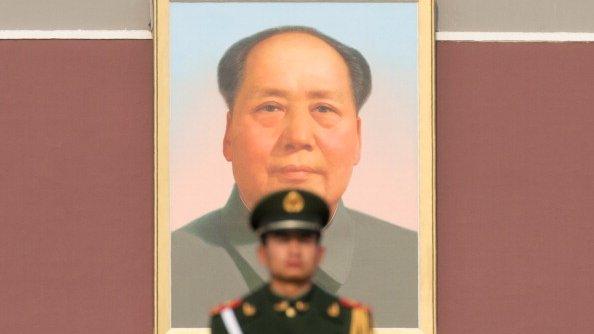

Zhou Yongkang was a powerful politburo member and head of China's Public Security Ministry in 2003

Taking down such formidable power structures carries very big risks of course.

This week another news report suggests that the former President Jiang Zemin has sent a message to the current leadership, telling them not to let the anti-corruption drive get out of hand.

Evan Osnos in the New Yorker quotes, external former party elder Chen Yun: "Fight corruption too little and destroy the country; fight it too much and destroy the Party."

China's sex trade has become a target of the anti-corruption clampdown

The BofAML report gives a clear sense of just how entwined corruption has become with Chinese economic growth.

It is not often that you find corporate bankers discussing the macroeconomic importance of prostitution, but they do so to make a point.

This year, the report points out, the anti-corruption campaign has been stepped up a gear and has targeted the sex trade in dozens of cities.

This has had an adverse impact on some businesses in the service industries, it says.

So perhaps today, Chen Yun would add a third observation to his musings about the difficult balance to be struck when tackling corruption - never mind the Party, fighting graft too hard just might destroy China's economy too.

- Published4 September 2013

- Published26 October 2013

- Published19 September 2013