Under the Dome: The smog film taking China by storm

- Published

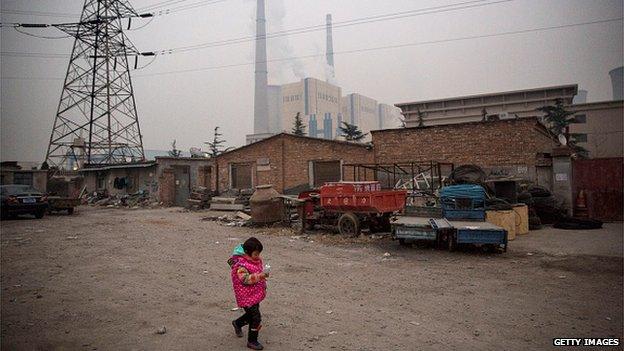

For many children growing up in China, pollution has become a normal part of life

Only in China would a documentary on air pollution garner more than 100 million views in less than 48 hours.

Renowned investigative journalist Chai Jing has been widely praised for using her own money - more than 1 million RMB ($159,000: £103,422) - to fund the film, called Under the Dome, external. She first started the documentary when her infant daughter developed a benign tumour in the womb, which Ms Chai blames on air pollution.

Standing in front of an audience in a simple white shirt and jeans, Ms Chai speaks plainly throughout the 103-minute video, which features a year-long investigation of China's noxious pollution problem.

At times, the documentary is deeply personal. Near the start of the documentary, Ms Chai interviews a six-year-old living in the coal-mining province of Shanxi, one of the most polluted places on earth.

"Have you ever seen stars?" Ms Chai asks. "No," replies the girl.

"Have you ever seen a blue sky?" "I have seen a sky that's a little bit blue," the girl tells her.

"But have you ever seen white clouds?" "No," the girl sighs.

'Work before the environment'

At other points, the documentary is deeply critical of the state's lax environmental laws. In one instance, Ms Chai follows a government inspector to measure the illegal pollutants coming from a coal-burning steel producer in central Hebei province.

Months later, she discovers the steel maker had yet to pay any fines.

CCTV's offices shrouded in smog - the organisation said Ms Chai shot the film independently

When she asks a provincial official why the coal-burning factories cannot be shut down, the answer is astonishingly blunt.

"It just doesn't work to sacrifice employment for the environment," Ms Chai is told.

Sources at Chinese state television CCTV, Ms Chai's former employer, confirmed the documentary was shot independently, but she had support from producers inside CCTV.

The original documentary was four hours long but another collaborator, tech entrepreneur Luo Yonghao, told her to cut it down to its current 103-minute length, the CCTV sources said.

However, it is clear that she also worked to gain government approval for the documentary before its release. In an interview with the People's Daily, a major state media outlet, Ms Chai notes that she sent the documentary script and interviews to the National People's Congress - China's parliament - and the government office working on China's new oil and gas laws. Both teams offered comments and feedback, she says.

One of Ms Chai's collaborators, an investigative journalist named Yuan Ling, told a Chinese news site that he viewed an earlier version of the documentary that questioned China's "development model".

"I think this is very hard to discuss and there is no need to worry about things that should be considered by a prime minister," Mr Yuan said. He told her to eliminate that section, which was absent from the final version of the documentary.

Igniting debate

China's government leaders will appear to be very responsive to the concerns raised by Under the Dome.

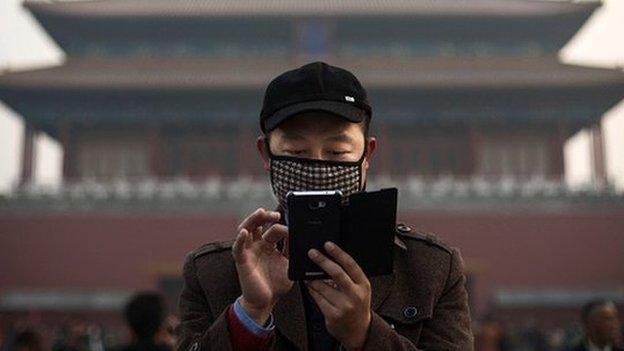

Pollution has become a hot political topic for China's leaders

Chai Jing's documentary was released on 28 February, less than a week before China's annual parliamentary session begins. China's central government is expected to pass an ambitious new law that hopes to impose tough new regulations on China's coal-burning polluters.

But in China, passing a law is one thing. Enforcing it is another.

Beijing could certainly use public pressure in its bid to carry out the new rules. Laws from the central government are commonly ignored by lower level officials, particularly when they might affect economic growth.

China named its new Environment Minister, Chen Jining, one day before the documentary was released. In his first press conference the day after his appointment, he noted he had already watched the documentary and had phoned Chai Jing to thank her for contribution.

Ms Chai and her collaborators declined interview requests from the BBC. Sources at CCTV explained the team were wary of the foreign media. After all, their Chinese-language documentary had already reached its intended target, the vast audience inside China.

Perhaps it does not matter who supported Ms Chai's documentary before it was made. Certainly, it has ignited a national debate across China, with millions stopping to pay attention to an issue that has been lingering in the air for years.

Could a journalist's film encourage individuals to change their way of life to address pollution?

"My home is less than 5km [three miles] away from my office," reads a typical comment, one of millions of responses. "Starting today, I will not drive to work except on special occasions. I salute Chai Jing and I will do my small part to help."

Ms Chai now occupies a rare place inside China - someone with the moral authority to speak publicly against government policy, even if she must first gain their tacit approval.

Perhaps we should have suspected Ms Chai was bound for a rare perch in China all along.

"A country is built upon individuals; she is constructed and determined by them," she said in a speech to the Beijing Journalists' Association in 2009.

"It is only if a country has people who seek truth, who are capable of independent thinking, who can record the truth, who build but do not take advantage of the land, who protect their constitutional rights, who know the world is imperfect but who do not slacken or give up - it is only if a country has this kind of mind and spirit that we can say we are proud of our country.

"It is only if a country can respect this kind of mind and spirit that we can say that we believe tomorrow will be a better day."

- Published3 February 2015

- Published25 February 2014

- Published12 November 2014