The 'model' example of China's one child policy

- Published

John Sudworth examines the painful legacy of China's one-child policy

Throughout the more than three decades of China's one child policy, few places have borne the brunt quite like Rudong, a county of some one million people in eastern Jiangsu province.

The policy came into effect here first, under Chairman Mao Zedong, and once it had become national policy, in 1979, Rudong's diligent family planning officials went about enforcing it with unrivalled zeal and enthusiasm.

One retired senior official recently gave an interview to Chinese state media, external in which he describes hunting down pregnant women, carting them off to hospital and then guarding them during their forced abortions.

An army of medical snoopers were tasked with the careful monitoring of wombs, using portable ultrasound devices, as well as the recording of menstrual cycles to ensure no-one was harbouring a hidden foetus.

Such practices have been by no means unique to Rudong, but Rudong became the national champion, held up as a "model" example and plastered with slogans proudly exclaiming the county's victory over female fertility.

Demographic bomb

Today the effects are everywhere to see.

Over the past 15 years or so, half the primary and secondary schools in the county have closed.

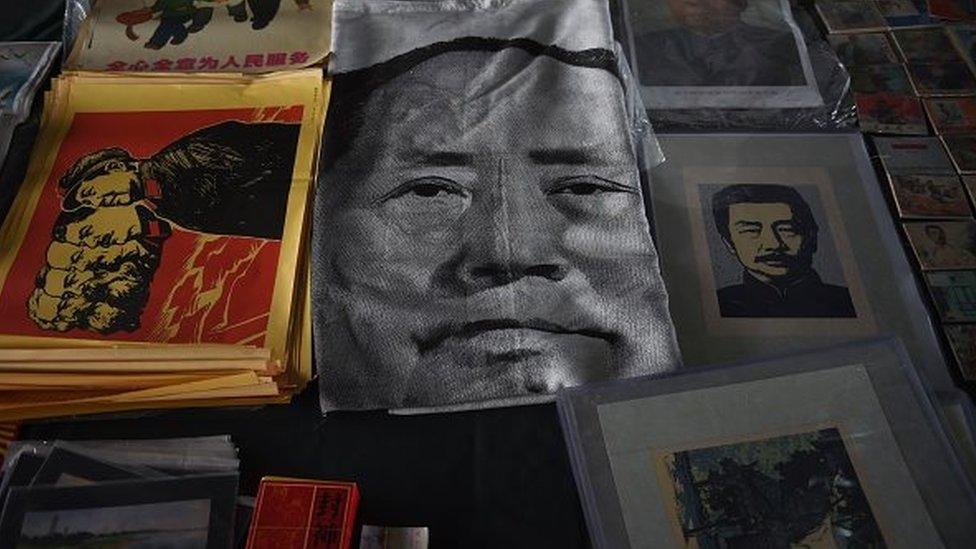

Chairman Mao Zedong first introduced the one child policy

About 30% of the population is now over the age of 50 - a demographic time bomb that holds up a terrifying spectre of rising social costs and falling worker numbers to a wider country that is only just a little way behind.

Seated around a dinner table in Rudong, I'm introduced to a family that perfectly sums up China's population crisis.

From great-great-grandmother on one side, through five generations, seated at the other end is just one, four-year-old great, great-granddaughter.

'I couldn't keep it'

Behind this generational imbalance lies a painful story that will be familiar to hundreds of millions of families across China.

"I did fall pregnant a second time," the grandmother sitting in the middle of the line, tells me, "but I had an abortion".

"Did you have a choice?" I ask.

"I couldn't keep it", she replies. "You either go willingly or the government comes for you."

A population crisis may be looming in China with not enough young people to support the elderly

Rudong has at last woken up to the enormous economic challenges and it has performed an extraordinary U-turn.

Under a relaxation of the national rules two years ago, couples in which at least one of the pair is an only child are now allowed to have a second child.

Rudong is actively encouraging them to do so with reports of cash grants of 5,000 yuan ($790; £515).

But for many here it is too little too late.

Gao Dequan, 63, is one of the many growing old alone.

His only son lives far away but he would have two more children were it not for the abortions his wife was forced to undergo.

"My biggest concern now is what will happen to me when I can't look after myself," he tells me.

Late or not, China's demographers and sociologists are growing increasingly loud in their insistence that the rules be relaxed further and there is wide speculation they may be about to get their wish.

Two child policy?

This week, China's Communist Party Central Committee has been holding a highly secretive meeting to draw up the country's next "Five Year Plan" and in a surprise announcement, has replaced the one child policy, with a universal two child policy.

In recent years the strict one child policy was relaxed

Old habits die hard though.

Even a two child policy will continue to act as a major drag on population growth and as with previous relaxations to the rules, one child families have become the social norm.

Many of the couples already eligible, perhaps as many as 90% or so, have chosen not to take advantage of the opportunity for a second child.

And of course, while the enforcement fervour may be nothing like it once was in places like Rudong, for those women who want more than two, the Communist Party's brutal control over their bodies and their fertility will remain unchecked.

- Published29 October 2015

- Published28 October 2015