A tale of two courts: How does Hong Kong compare to China?

- Published

The leaders of Hong Kong's pro-democracy Umbrella Movement turned up at the city's Eastern Magistrates Court to cheers from supporters

A visit to a courthouse can tell you much about the norms and values of any society.

And there can be few starker ways to experience the differences between Hong Kong and mainland China.

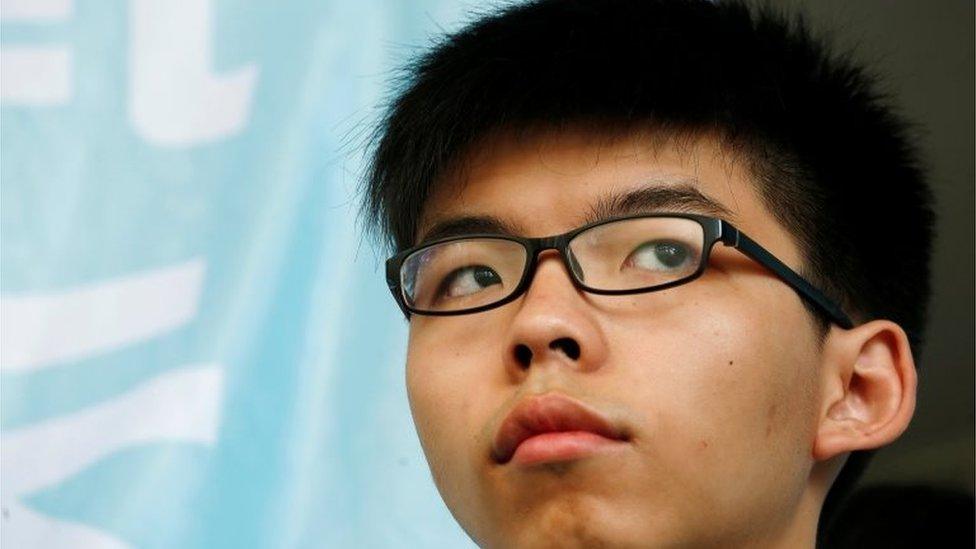

Joshua Wong, Nathan Law and Alex Chow - the leaders of Hong Kong's pro-democracy Umbrella Movement - turned up at the city's Eastern Magistrates Court to cheers from supporters.

They stood on the steps and made speeches into a portable PA system while a large crowd of waiting journalists surged out of the press area set aside for them and onto the court steps.

The police looked on good-naturedly.

Inside, seats were allocated on a first come, first serve basis but an extra allowance was made for the high level of interest and some reporters were allowed to stand.

Joshua Wong will begin serving his community service order as a helper in his local library

And then, as the lead prosecutor made a somewhat faltering pitch to have the three defendants thrown into jail, the magistrate made mincemeat of his arguments.

It was an exercise in openness and transparency, as legal principles and precedents were debated.

And at the end of it all the three young men once again walked free with the court rejecting the prosecution claim that the original sentences had been too lenient.

Joshua Wong, a teenager who became the poster-boy for the protest movement that dared to stand up to Beijing, will begin serving his community service order on Friday.

He will work as a helper in his local library.

For a total of 80 hours.

'The hand of Beijing'

In contrast, I've been to many courts in an attempt to cover many trials in many cities in mainland China.

I've rarely been allowed to get close to one, let alone in one.

I've lost count of the times I've seen supporters of the accused dragged away - with even family members, desperate for news of a long-detained loved one, loaded into the waiting police buses.

China's judges convict more than 99.9% of defendants who appear before them

The proceedings, gleaned only from reports in the Communist Party-controlled media, are a glimpse of a system that is anything but transparent.

The country's judges, also Communist Party-controlled of course, convict more than 99.9% of defendants who appear before them.

And for those offences that involve defying the will of the Communist Party - simply calling for political reform for example - the accused can expect to serve years in prison.

It puts Wong's library service into stark relief and illustrates what's at stake in the fractious, polarised fight for the future of this city.

On one side, there are many - particularly those who felt inconvenienced by the street blockades two years ago - who will feel frustration with what will seem an unduly lenient punishment.

But on the other side, for the pro-democracy camp, the striking demonstration of judicial independence suggests that Hong Kong's freedoms are not under the kind of immediate threat from Beijing that they sometimes claim.

"The hand of Beijing is everywhere in Hong Kong," Nathan Law told me ahead of the sentence review hearing.

Of course, the real debate is over how best to safeguard these freedoms in the future.

Ironically, two years on, the direct result of the Umbrella Movement is that Hong Kong now has less democracy than it would have done.

The umbrella movement saw thousands protesting in Hong Kong in a pro-democracy civil disobedience movement

Next year's election for the city's highest political office were meant to be the first to take place under universal suffrage.

But the pro-democracy movement has blocked that plan because of its objections to the rules - set down in the city's constitution and insisted on by Beijing - that the candidates for that election must be pre-vetted by a nominating committee.

The committee's make-up locks in a pro-establishment bias and would make it all but impossible for a pro-democratic reform candidate to make it onto the ballot.

So the debate can be summed up like this; for the pro-Beijing camp, some democracy is better than none, for the anti-Beijing camp, sham democracy is no democracy at all.

The debate will rage on in a Hong Kong becoming more polarised, fractious and nervous about its relationship with an increasingly assertive and powerful China.

As if to prove the point, after the sentencing ruling, scuffles broke out on the steps of the court with protesters from each side trading blows.

Freedom in abundance?

Back in Beijing, where I live, in my conversations with people I meet and interview I rarely hear people complain about the lack of democracy.

The idea of voting seems an abstract, distant irrelevance to most people's lives.

In Hong Kong, the idea of being able to hold authority fairly to account is one valued by all sides

But people are acutely aware of their lack of other rights and, in particular, the impossibility of getting a fair hearing when they find themselves - as so many do - on the wrong end of a land dispute or the victim of medical negligence or snarled up in a myriad of other minor injustices.

The idea of being able to hold authority fairly to account in a court of law is a distant fantasy.

Hong Kong has that freedom in abundance and it is valued by all sides in the current debate.

One side believes it can only be preserved through pragmatic engagement with the sovereign power in Beijing.

The other that only genuine democracy can act as a bulwark against the gradual erosion of Hong Kong's special status by a political system that neither understands or values it.

Outside the court, the three young democracy activists vowed to use their freedom to continue to protest.

First though, there's library service to attend to.

- Published4 July 2016

- Published2 August 2016

- Published2 December 2014

- Published21 July 2016