Is this proof Hong Kong’s 'Umbrella Protests' failed?

- Published

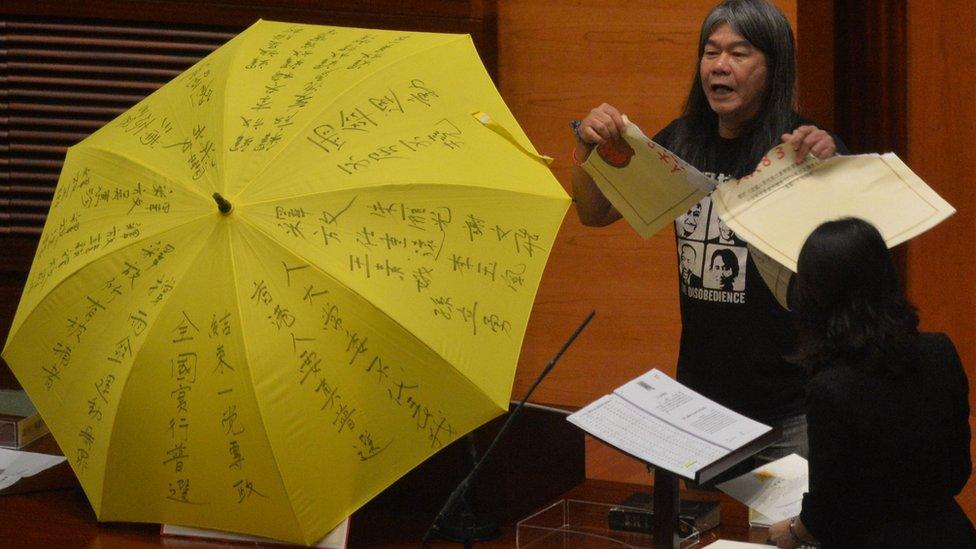

Umbrellas became a symbol of the 2014 pro-democracy protests

Hong Kong politics has been stormier than usual lately.

There's been swearing and scuffling in parliament, court battles, and tens of thousands of protesters in the streets.

And, to cap it all off, the Beijing government has intervened directly with a legal ruling to disqualify two legislators - prompting government lawyers to say: "The headmaster has spoken."

Yet, ironically, it's a quieter, less dramatic event that shows the fundamental sticking point in Hong Kong politics.

Hong Kong has Election Committee, external elections on Sunday, but you could call them elections with Chinese characteristics.

Things have been rowdy in parliament - with swearing and scuffling in the chamber

A small proportion of Hong Kongers (246,440 out of Hong Kong's 3.8 million registered voters) have the right to vote for people representing their professional sector - making up an Election Committee of 1,200 people. These 1,200 people are the only people who can vote on who becomes Hong Kong's next leader.

Rebellious lawmaker Yau Wai-ching

Who are the new faces in Hong Kong politics?

And hundreds of seats - mostly in pro-Beijing sectors - have already been filled, because there were no elections, or the candidates ran unopposed.

About 6% of Hong Kong's voters can take part in the Election Committee polls

The fact that this system is undemocratic is what drove tens of thousands of protesters to take over Hong Kong's streets in 2014. The movement became known as "Occupy Central" - or, the "Umbrella Protests", after protesters used umbrellas to shield themselves from pepper spray fired by the police.

The unprecedented - but mostly peaceful - protests lasted several weeks. The sight of students doing their homework while sitting in the streets, or young protesters being teargassed by police, caught the attention of people around the world.

The protests paralysed parts of Hong Kong's business district for weeks

Yet, two years later, Hong Kong's leader is about to be chosen by the same 1,200-person committee - and critics say that the protests failed to achieve any practical results - except, possibly, a more divided society.

This may not be completely fair. They were a political awakening for many young people in Hong Kong - and several have now become pro-democracy activists or won seats in September's parliamentary elections.

The protests were predominantly led by young people. The placards read "Hope comes from the people, change begins from struggle" and "peaceful struggle, no compromises".

But in practical terms, the so-called "Umbrella Protests" failed to achieve any concessions from Beijing.

The irony is that Hong Kong could have had direct elections for its leader in 2017.

The Chinese government had promised the territory universal suffrage - but said voters would only be able to choose from a list of two or three candidates, pre-vetted by a nominating committee dominated by pro-Beijing members.

Democracy activists derided this as "fake democracy", and the proposal was voted down in parliament.

Hong Kong's relationship with mainland China has been tense in recent years

Critics accuse Beijing of breaking two promises it made:

That Hong Kong's leader would ultimately be chosen "by universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly representative nominating committee in accordance with democratic procedures", as outlined, external in the territory's mini-constitution

That the ex-colony would be allowed "a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs" for 50 years after it returned to Chinese rule, as agreed with the British government, external

Did Beijing break the first promise? It depends on who you talk to. Clearly Beijing, and the democracy activists, have very different definitions of the terms "universal suffrage" "broadly representative" and "in accordance with democratic procedures".

Similarly, the Chinese government would argue that Hong Kong enjoys a high degree of autonomy under the "One Country Two systems" model.

Tens of thousands have turned out to protests to support the Chinese government

But critics point to a series of recent events that have worried many Hong Kongers, including the disappearance of five Hong Kong booksellers, and artists and writers saying they are under increased pressure to self-censor.

Activists have accused Beijing of meddling in Hong Kong's affairs with an "invisible hand".

And it's that perception of growing mainland Chinese influence that has propelled more young people into supporting independence, or arguing for more radical politics.

This also worries some Hong Kongers, who point out that protests organised by some radical groups have turned violent.

Surprise victories

Anger at the Chinese authorities, and disillusionment with traditional pro-democracy parties, helped propel several new faces to victory in Hong Kong's legislative council elections in September.

Amongst them were Sixtus Leung and Yau Wai-ching, from a pro-independence party set up after the Umbrella Protests, and Nathan Law, Lau Siu-lai and Edward Yiu, who were all active in the protests.

Nathan Law (centre) was one of a new wave of activists elected to parliament, and won 50,818 votes

Their success was hailed as a sign of Hong Kong's new generation of democracy activists taking political power for the first time.

But then the government took Mr Leung and Ms Yau to court after they insulted China while being sworn in - and its argument was bolstered when Beijing also issued a controversial legal ruling that effectively invalidated their oaths.

Now, the government is using the same ruling in an attempt to disqualify Mr Law, Ms Lau and Mr Yiu, as well as "Longhair" Leung Kwok-hung, a veteran pro-democracy politician.

Clockwise from top left: Leung Kwok-hung, Lau Siu-lai, Sixtus Leung, Yau Wai-ching, Nathan Law and Edward Yiu

So, just three months after winning elections, several of Hong Kong's new political faces - who won a combined 185,727 votes - could be removed from power by a government that was not democratically elected.

It is against this backdrop that the Election Committee vote is taking place.

An unprecedented number of pro-democracy candidates are taking part this year and the pro-democracy camp hopes to win at least 300 seats, so it has more negotiating power over who becomes Hong Kong's next leader.

Many have criticised the move to disqualify democratically-elected legislators

But even with a quarter of the 1,200 seats, they will be massively outnumbered by pro-Beijing and pro-establishment groups, who are likely to vote for whichever candidate is backed by Beijing.

It will leave many in Hong Kong wondering: Was the partial democracy offered by Beijing in 2014 the better deal? Where do Hong Kong's democrats go from here?

And, if the massive umbrella protests could not achieve political change - what will?

- Published18 June 2015

- Published2 December 2016

- Published7 November 2016