Looking for Rohmer challenges China's cinematic gay taboo

- Published

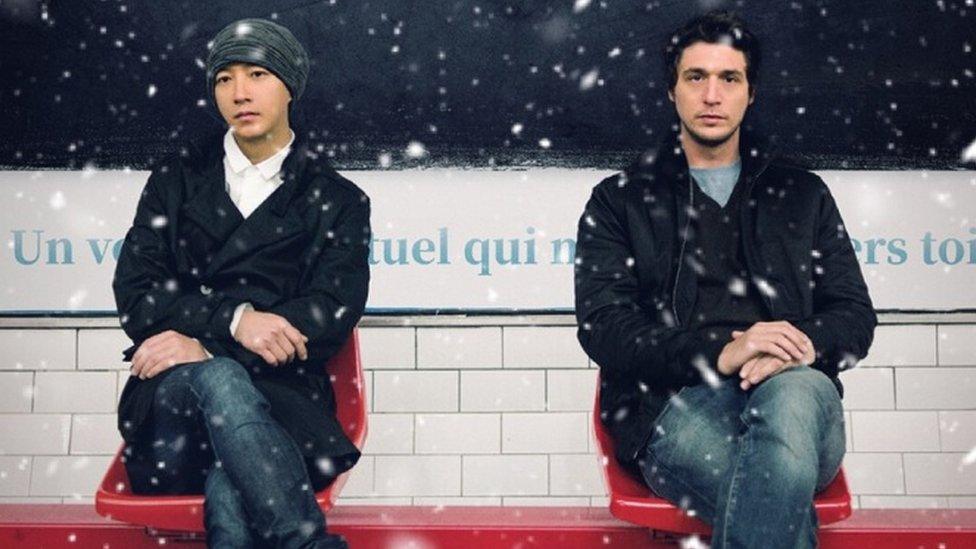

Looking for Rohmer tells the story of love and friendship between two men

A low-budget film has made headlines in China, not for its glowing success at the box office or critical acclaim, but simply because it made it into cinemas at all.

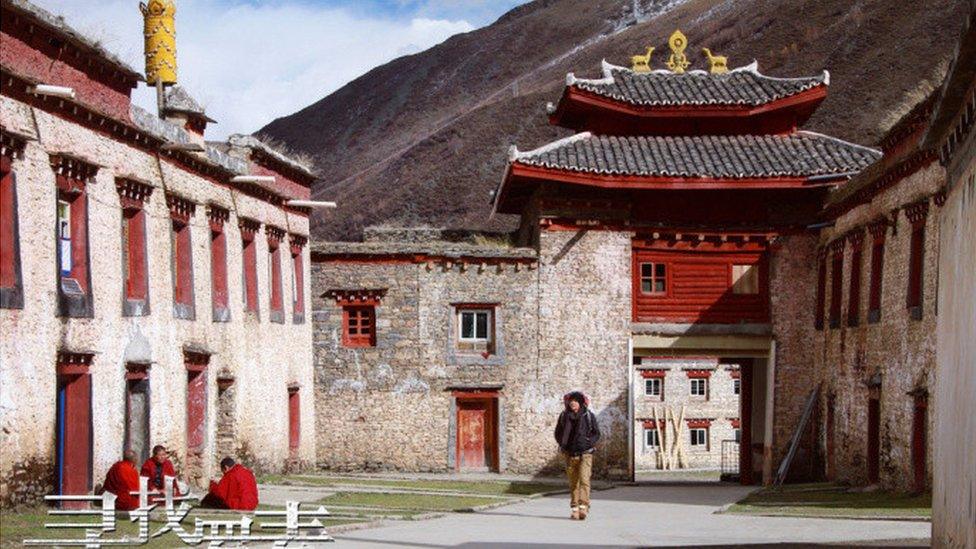

Looking for Rohmer, adapted from a novel, is a story of love and friendship between two men, one Chinese the other French. A co-production between China and France, the film was shot in Tibet, Provence, Paris and Beijing.

Three weeks on from its debut in April, the film's domestic gross box office had barely surpassed $600,000 (£441,772). And it has received relatively poor reviews from both moviegoers and critics, scoring only 4.5 out of 10 on Douban, China's popular movie review platform.

Looking for Rohmer was shot in various locations including Beijing and Tibet

By any normal standard, it doesn't look like a box office hit.

But it is successful in a different sense, because is regarded by many as China's first ever publicly screened movie about homosexuality.

Censorship battles

Before any film can make it to the big screen in China, it must be submitted to the State Administration of Radio Film and Television (SARFT) for examination.

Many Chinese people hate SARFT because they believe it bans interesting movies and makes ridiculous revision suggestions - and neither the reasons nor the decision-making process are ever made public.

So whether a movie survives the SARFT's strict tests is often discussed at Chinese dinner tables. Challenging topics such as homosexuality are almost never granted the green light.

As a result, many LGBT-themed works can only be seen on alternative platforms, or at overseas film festivals.

There is one notable exception.

Back in 1993, Farewell My Concubine - regarded as one of the great works of Chinese cinema - made it to the big screen.

It reveals the turbulence and brutality of China's modern history through the lives of two Peking Opera artists, and also explores the love and hate that burns between those two men.

The film also criticises the Cultural Revolution. The award-winning film by renowned director Chen Kaige managed to clear the censorship tests more than two decades ago, and is still screened proudly today. Mr Chen has described it as a "miracle".

But that openness wasn't to last.

Since Farewell My Concubine, the authorities seem to be moving backward, tightening regulations and becoming even stricter.

In June last year, China published a set of general guidelines for censoring audio-visual content on the internet. It listed categories of content that must be prohibited, including material that is "obscene, pornographic, vulgar and of low level interest".

Homosexuality is included under the category of "abnormal sexual relationships and sexual behaviours", right next to sexual assault, sexual abuse and sexual violence.

In response to those laws, last month social media network Weibo said it would scrub all gay content from the platform. But the move sparked a massive outcry, prompting the company to reverse the ban a few days later.

The 'sleeve cutting addiction'

But homosexuality is not invisible in Chinese history.

Stories of kings, princes, aristocrats and their sexual partners are dotted throughout Chinese literature - mostly using vague language and metaphors.

There's also the famous tale of Emperor Ai, who woke up one morning to find his sleeves pressed underneath his male companion Dong Xian's body. So he could leave without waking his lover, the emperor cut his sleeve off using a sword. Ever since, "sleeve cutting addiction" has become a common euphemism for homosexuality in China.

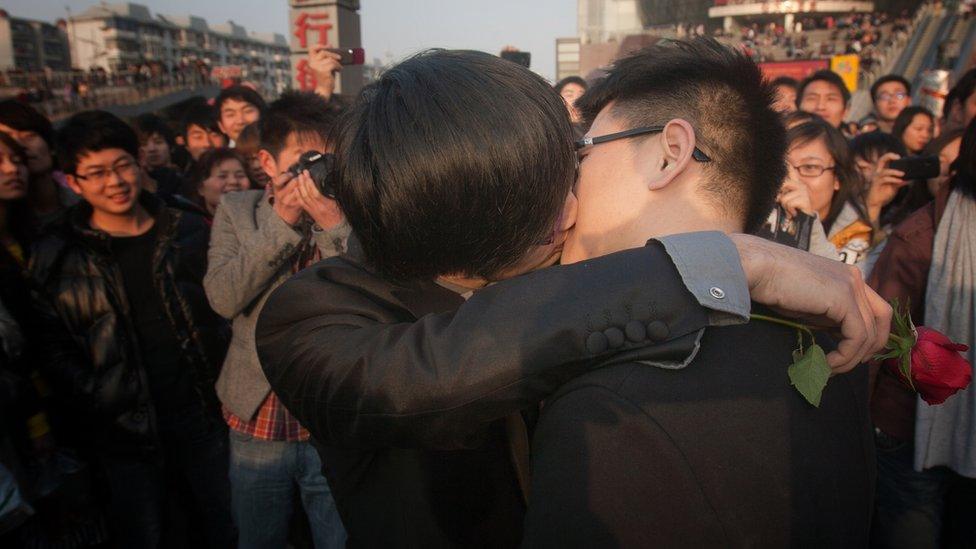

Though gay marriage is officially not allowed, some gay couples have held ceremonial celebrations to raise awareness

During the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, homosexuality was openly prosecuted for the first time. People found to have engaged in homosexual practices were sentenced as criminals, and faced severe punishment.

Many were paraded publicly with the sign "buggery offenders" on their chests. And China's homosexual communities have since gone underground.

It wasn't until 2001 that China removed homosexuality from the catalogue of mental diseases. And as Chinese society gradually opened up, gay culture and gay movies started to spring up.

But even today, remaining obscure and low key is vital to the survival of the homosexual genre in China's cultural domain.

Directors and playwrights in China walk a fine line and often have to play games in the script if they want commercial success.

They can give endless clues and hints, and leave the audience guessing, but explicit gay sex scenes or pronounced gay love must be avoided.

Obscured from view

It took four years for Looking for Rohmer to clear all obstacles and finally make it into the cinemas.

Movie reviewers have rushed to call it a "milestone" moment in Chinese movie history.

Domestic media described it as "China's first publicly shown gay movie" and some even hailed it the "Chinese and French version of Brokeback Mountain".

But despite the fanfare, the two lead actors don't even hold hands during the entire 1.5 hours.

Homosexuality was decriminalised in China more than two decades ago

That's why - despite its significance - Looking for Rohmer hasn't been met with too many cheers from China's LGBT community. They don't see it as a sign that a new era of acceptance has arrived.

Some think it is just a fluke. And others don't even consider it a gay movie.

"I thought I'd come to the cinema to show support. But to my disappointment, I didn't see much gay love. I only saw natural sceneries," commented one Weibo user.

"The movie is still inside the closet," another user added.

- Published16 April 2018

- Published15 November 2017

- Published16 July 2017