China congress: How authorities censor your thoughts

- Published

What can and can't you say in China?

If you control public communication you can control the way people think and how they behave. That's what Xi Jinping's government is counting on.

And it is never more true than at the time of major political gatherings.

The Communist Party Congress, held every five years, is set to begin next week: an event which will culminate in the revelation of the new leadership team behind General Secretary Xi.

So the censors here are poised to restrict with one hand and disseminate with the other.

What they're looking out for are key words and expressions popping up in social media. Anything signalling an intention to protest or ridiculing the country's senior political figures will be blocked and potentially see a user reported to the authorities.

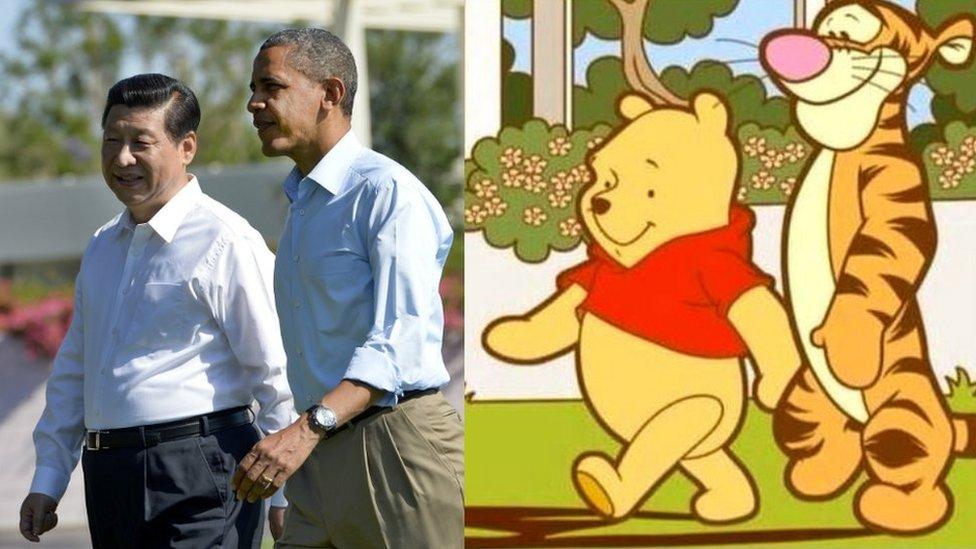

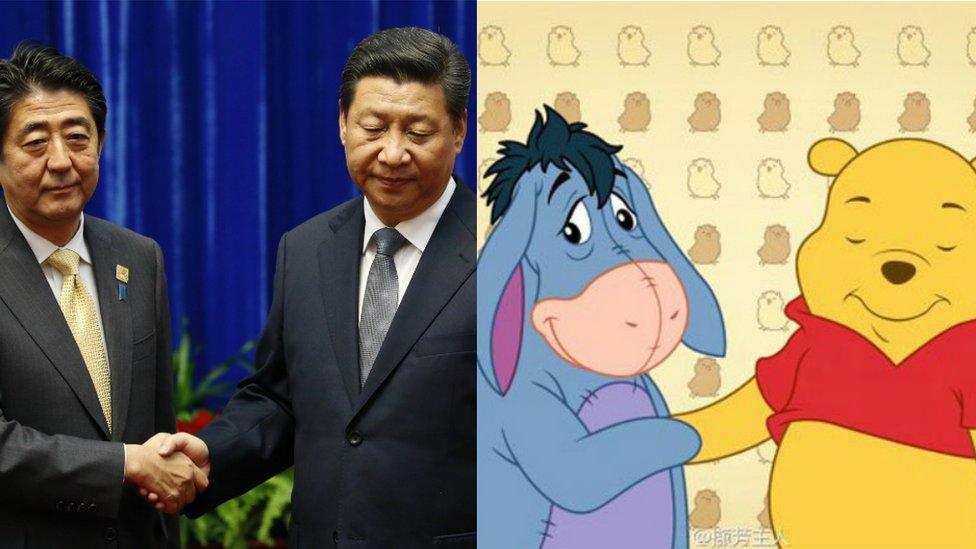

For example, a message featuring the name of this country's ever-more powerful leader and his sometimes-used nickname "Winnie the Pooh" (小熊维尼) will simply not go through to group discussions on the messaging app WeChat.

Funny stickers featuring Mr Xi or previous Chinese leaders also can't be sent to chat groups.

This meme comparing Xi Jinping and former US President Barack Obama to Winnie the Pooh and Tigger has been censored in China

China has all the appearances of an increasingly open society: flashy new cities with Hollywood movies advertised on bus stops; digital currency taken up like nowhere else; cool kids getting around on hire bikes zooming through a gleaming modern existence.

And yet, since Mr Xi came to power five years ago, public discourse has been increasingly censored to try and control everything from political thought to sexual activity.

Olympic freedom

In the lead up to the Olympic Games in 2008, it felt as if freedom of expression was ever on the rise here.

New laws allowed foreign reporters to travel around the country without specific permission from local governments.

It's hard to believe it, but Google searches were not blocked then.

Investigative journalism from local Chinese publications - like the Southern Weekend newspaper and Caijing magazine - was becoming as good as anywhere in the world.

I remember being at a function where a group of journalists were speaking to one of the foreign affairs ministry spokespeople. We had some concern or other, and he was reassuring us that everything would be all right.

"Don't worry," he said, smiling as he pushed an imaginary truck gear into position. "In China we only have one gear, and it's forward."

It sometimes doesn't feel like that now.

The Great Firewall

Just as China has its Great Wall, so does it also have a powerful internet firewall to block "undesirable" sites

"You can't control the internet," is something people would say in those years - part mantra, part celebration of a new global reality.

But Chinese officials have worked out that actually, you can.

Rather than connecting to the internet, this country has something more like an intranet within the boundaries of the Great Firewall of China.

Sites like Amnesty International, Facebook, and Twitter are unreachable for most Chinese, unless they have use of a virtual private network (VPN), which effectively punts their computer over the Great Firewall.

So, with the congress approaching, there's been an assault on VPN use. The government has ordered Apple to remove all VPNs from its Chinese app store.

The company has decided in favour of not being kicked out of this enormous market and is doing what Beijing wants.

Years ago Google was given a similar ultimatum: allow Chinese officials to censor search results or you're gone. Google didn't cave in, and was blocked.

Watching WeChat

WeChat is widely used in China

China's most effective censorship tool is also the country's most widespread method of communication.

Pretty much everybody here uses the phone app WeChat. It has text messaging, group chats, photo sharing, location searching and electronic payments.

During periods of political sensitivity - like now - key words will trigger the blocking or monitoring of a post. If sensitive enough, they could even lead to state security knocking on your door.

New regulations also make a person who sets up a group chat responsible for what's said amongst the group.

As you can imagine, the administrators of football team chats might be feeling a little nervous about the content of late night posts from drunken players.

Some will wonder how this is all possible as the app is not owned by the government but run by the hugely-powerful Chinese company Tencent.

Well, under new regulations from the Cyber Administration of China, private entities which run these platforms are required to not only enforce content restrictions but also report those who violate them to the "relevant authorities".

For many Chinese people - even those overseas - WeChat has also become their main news feed. If you restrict this content you can close out certain news coverage.

Potential challengers to WeChat's virtual monopoly are also being reined in. WhatsApp is not 100% within the domain of the Chinese state.

So, at times in recent weeks, its use has been impossible to reach without a VPN.

It is not clear whether the disruption of WhatsApp is a temporary measure to coincide with the congress or yet another restriction that's here to stay.

Tight grip on the press

Mr Xi visited state broadcaster CCTV's imposing headquarters in Beijing last year

It is no secret that every Chinese newspaper and television station is under the complete control of the Communist Party.

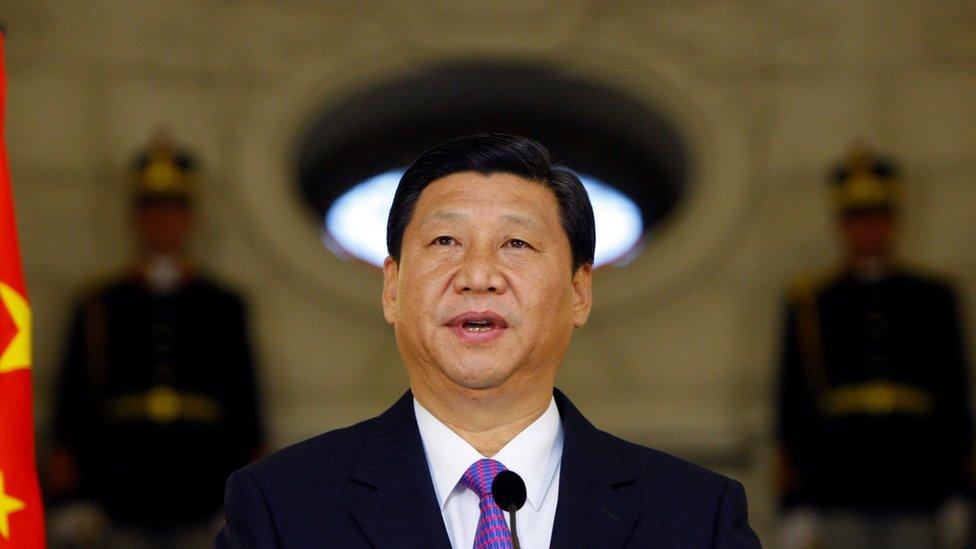

And yet last year, when Mr Xi visited the People's Daily newspaper, Xinhua wire service and state broadcaster CCTV, he still demanded the absolute loyalty of reporters who should follow the Party's leadership in "politics, thought and action".

But, just in case some journalists didn't get the memo, a set of rules have been sent around governing coverage of this year's congress, requiring all interviews with experts or scholars to be approved by the outlet's "work unit leadership" and the central propaganda department.

However, China's censorship and propaganda model is also going beyond sensitive political matters.

Online bookstores must now work under a rating system from the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television which includes the promotion of "moral values".

Popular blogs focusing on celebrity scandals and the intrigues of the rich and famous have been forced to close.

To talk about such matters has been deemed to be not in keeping with "core socialist values".

No naughty dramas

For a time, cheap online video dramas were pushing out the boundaries of what could be viewed here. There was a gay sitcom, for example.

But digital platforms have been ordered to stop showing hundreds of foreign shows, and their locally produced material is expected to follow the same restrictions as television.

As it is, on Chinese TV you rarely see anything approaching a passionate kiss.

Two years ago a TV drama was forced to reframe and zoom in on its shots so as to crop out the generous cleavage of its 7th Century maidens, in order to remain on air.

Many in China feel the authorities have gone too far in censoring The Empress of China, as John Sudworth reports

Thus goes the creeping imposition of a state-sanctioned morality under Mr Xi's administration.

Last month, TV dramas were given notice of a new set of rules governing their content. They should "enhance people's cultural taste" and "strengthen spiritual civilisation".

Directors are supposed to come up with engaging characters beyond the realms of lewd behaviour, extra-marital affairs, gambling, drugs, homosexuality and other forms of "immoral" behaviour.

The notice suggested eulogising the Communist Party of China, the country, the people and also national heroes. And one figure is emerging via the propaganda machine to stand head and shoulders above all others.

The cult of Xi?

As the censors shut down dissent, the party is urging a way of thinking about all that's good in China and tracing it back to a single source - Xi Jinping.

An exhibition focusing on the recent achievements of the Chinese government has opened in Beijing.

Vast rooms are dedicated to science, transport, the military, the economy, sport, ethnic minorities, and they are all dominated by massive photos of Xi Jinping. There must be hundreds of them.

Songs have been written celebrating Chinese President Xi Jinping, one even has an accompanying dance routine

The English language newspaper China Daily has been rolling out a series of front page stories - one every day - about the "impact of" a visit from Mr Xi on various villages, towns and cities after the General Secretary passed on his advice.

"He asked people to protect the lake", "President Xi proposed moving people in the villages to the new settlement", "Xi emphasised the importance of afforestation", et cetera.

Some here are joking that this type of reporting is not all that far from what you might expect in the North Korean press describing its own god-like leaders.

When Chinese officials make speeches now, they refer to this or that aspect of what they're up to "with Xi Jinping at the core".

It goes without saying that you cannot question "the core" without this nation's considerable censorship apparatus crashing down upon you.

But, short of such an obvious breach, the rules regarding what can and can't be said, broadcast, forwarded, analysed are thought to be kept deliberately vague.

In this way, everyone is on their toes and the authorities can shut down what they like at any time without having to give a reason.

Editors, cartoonists, reporters, directors, bloggers, comedians, administrators running social media platforms and ordinary Chinese citizens posting to their friends are all staying well clear of certain subjects just in case it lands them in hot water.

In short: Chinese censorship works, and plenty of other governments around the world are looking on with admiration.

- Published17 July 2017

- Published3 September 2015

- Published26 September 2017

- Published23 February 2016

- Published12 January 2015

- Published16 March 2016

- Published29 October 2016

- Published18 October 2015