Beijing Olympics 2008: A hope lost or fulfilled?

- Published

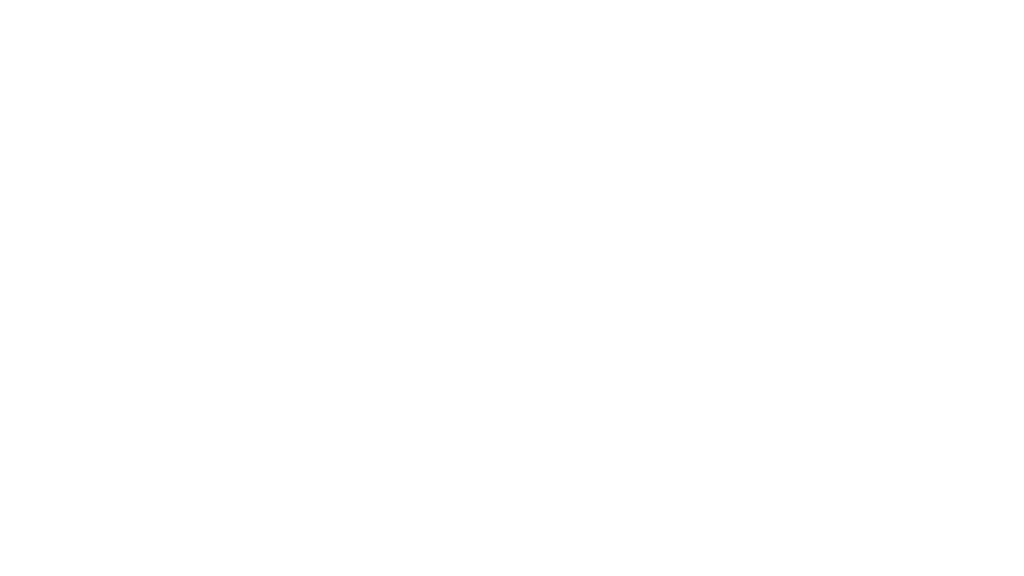

The Bird's Nest stadium where the Olympics were held is one of Beijing's most famous buildings

Ten years ago this week, the Beijing Olympic Games drummed themselves onto television screens across the globe.

It brought waves of hype in China that the country was preparing to celebrate not only a festival of sport but the return of the "Middle Kingdom" to the centre of the universe.

At least that is how it felt at the time.

In the years leading up to the Olympics it was as if there was nothing this place could not achieve. The economy was charging ahead, newspapers were starting to dig up investigative stories, millions of poor people were able to buy electrical goods for the first time and bars and restaurants were heaving with 24-hour hedonistic temptation.

"There was a party every night. That's how I felt," laughs 45-year-old architect Dong Hao.

"The whole city; the whole country was not only about fun but that a lot of things were now possible. Everything was more tolerant and more liberal."

Dong Hao is a native of Beijing and studied in New York. Before, say, 2005 you might have expected somebody like him to make his career overseas but the pre-Olympic potential drew him home.

Dong Hao calls the Beijing of 2008 a "lot more liberal" than it had been

After all he is an architect and there was a building boom. The Olympics were coming and enormous structures with breath-taking designs were being erected at breakneck speed.

Beijing Capital Airport, Beijing South Train Station, the National Centre for the Performing Arts, the Water Cube and, of course, the Bird's Nest Olympic stadium… up up up!

"Everyone wanted something exciting and maybe it was unreasonable," says Dong Hao.

"Maybe not functional, maybe not necessary: it doesn't matter, let's have it!"

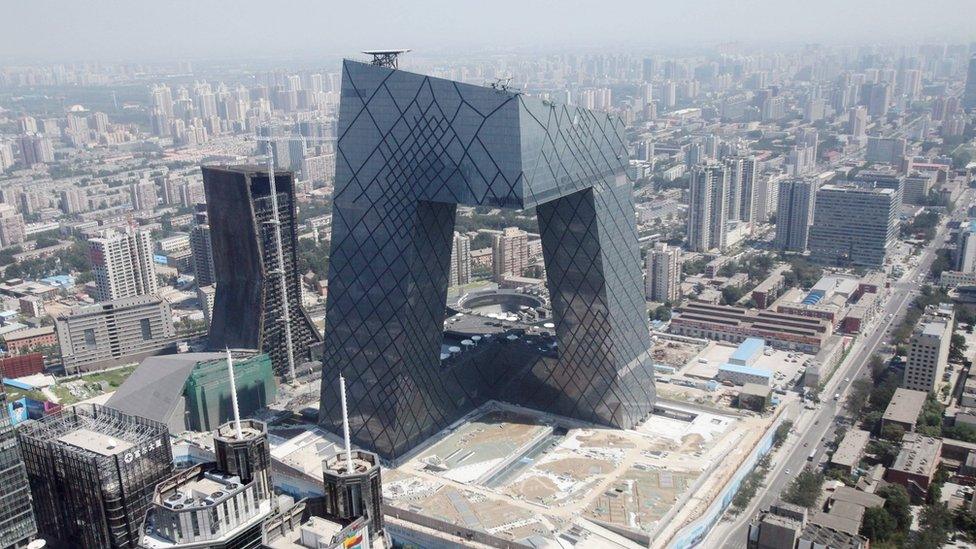

The CCTV building has two distinctive angulated towers

Some of the unique possibilities of the pre-Olympic frenzy may have dried up but that the process is now more considered, he says.

"Now the market and the clients are more mature."

Dong Hao adds that it is pretty hard to impress anyone in China with your design now that people have seen the China Central Television (CCTV) building.

When two huge towers were growing, jutting up and out to eventually link and become the seemingly impossible to balance CCTV headquarters, I remember them initially being joined by an enormous net.

Along that net you could see Chinese workers up in the air crawling from one side to the other.

It looked terrifying.

There aren't exact figures on industrial accidents accompanying the speed with which the city's architectural wonders appeared, but they certainly provided a lot of jobs for once poor farmers.

From building to renovating

There were so many labourers in Beijing at the time sleeping in on-site dormitories that nobody knew how many millions really lived here.

Last year, the city government launched a deliberate campaign to reduce what one official called the "low-end population". Entire suburbs housing the poor have been levelled and many of the small enterprises where they worked are gone.

Whole districts were swept away almost overnight in the radical radical clean-up of Beijing

But some working class folk from outside Beijing are still holding on.

In the run up to the Games, Sun Jingsu came from Hennan Province to find a better life. He is still here, next to the Bird's Nest using a trowel to spread cement across a new fence.

"There's not as much construction work as there used to be," he says. "Now we're doing renovations and the like."

"I don't really know," he says when I ask him about his future plans.

"But I guess it must be back in the countryside."

Sun Jingsu earns around £22 a day

Apart from finding work, a major problem for manual labourers now is affordability.

Sun Jingsu proudly tells me he earns more than 200 yuan ($29; £22) a day. It's above the average for this type of work, but it's what some people in Beijing spend on lunch.

A short walk down the street, waitress Wei Xufang is selling fruit to customers.

She came to Beijing from Shanxi, where she'd watched the Olympics as a 15 year old. She thinks Chinese people are as positive about the future now as they were 10 years ago.

You only have to look at the city's streetscape to appreciate the Olympic legacy, she says.

"Beijing is such a clean city. There are always people cleaning it."

More than just sport

Ordinary Chinese people, known affectionately as "lao bai xing", were supposed to get more healthy and active as a result of the Games. Mass fitness displays were featured on television and more participation in sport encouraged.

But some say this hasn't really had its intended results.

"You couldn't really say that the Olympics had a huge impact on say children playing sport", says junior soccer coach Yao Liwei. "The football world cup has had a much bigger impact."

The ex-footballer also thinks that China has not improved its overall sporting performance since the Games.

And yet Beijing's Olympics was about much more than just sport.

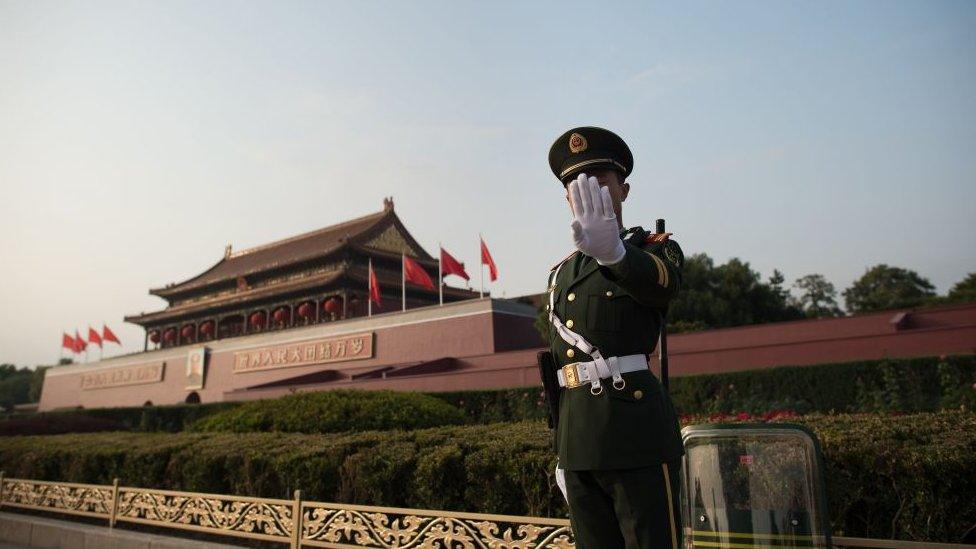

The city had tried and failed to secure the Games in the years following the bloody 1989 Tiananmen Square clashes so it had to make certain promises in order to secure this most coveted prize.

Officials said they would allow designated protest sites during the Olympics. In practice though, the Communist Party reneged on this.

Protests were technically allowed during the Olympics, though this was not put into practice

There were so-called "protest locations" but you needed to somehow apply for and get approval to use them. This was never going to be allowed in any meaningful way.

Rules governing the foreign press were also changed, allowing correspondents to travel around without the permission of provincial Party officials.

China's media remained state controlled but started to do more real reporting, like when a television crew went undercover to expose a brick kiln using children, many kidnapped, as cheap labour., external

However, former journalist Yuen Chan says this was still well short of some sort of golden age.

"Despite all the hype about relaxed regulations for the media in the run-up to the Olympics in 2008 the authorities' grip on the domestic media was still tight," she says.

The Hong Kong based ex-reporter says the reason it seems worse now is that the Chinese state has simply become better at censorship.

In 2008 "it was less sophisticated and more was able to slip through the cracks," she says.

"The space is far more strictly and efficiently controlled now, as we can see through the deployment of technology to boost surveillance systems at all levels".

'People watching you'

The once exploding art scene here has also taken a hit from the censors since the more freewheeling period ten years ago.

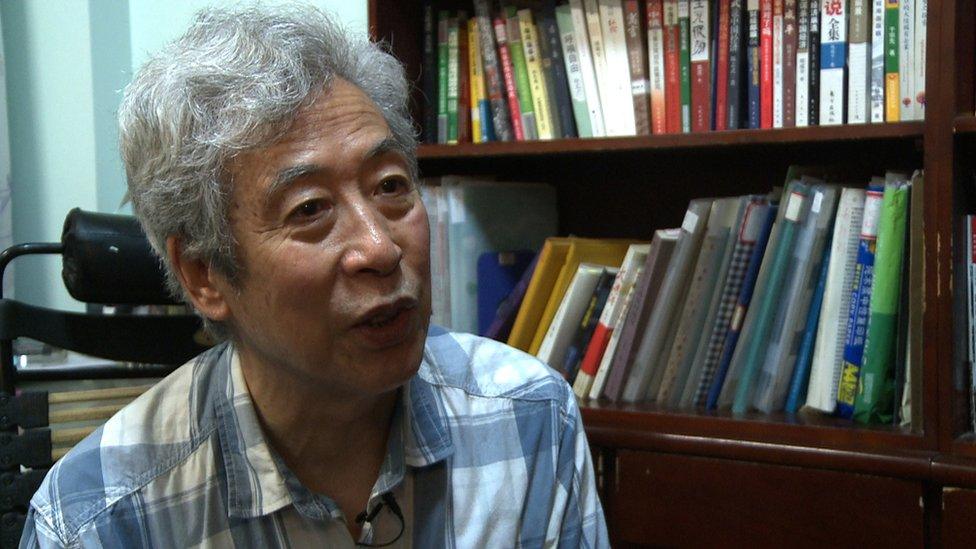

"Like many in China at that time I was hoping that the Chinese people might be getting a better chance to know the world and that there might be more freedom of expression," says artist Guo Jian.

He returned to China after living in Australia for years, full of pre-Olympic hope for his homeland.

"I thought we would be gradually moving towards a rule of law society and that we would see political reforms again; that China would embrace the world."

But while his career flourished, he also saw freedom disappearing.

"There was less internet freedom, there were people watching you," he says.

"I was told not to do any shows which were too provocative and to not speak to the media and especially the western media."

Guo Jian was kicked out of China in 2014

The Australian passport holder tried to make a go of it, balancing artistic expression with the need to minimise the extent to which the authorities might become upset with his work.

But when he planned to cover a diorama of Tiananmen Square with rotting meat - a clear reference to the crackdown - this became too much for the officials.

In 2014, Guo Jian was kicked out the country.

"I was hoping that China would be moving to a better place," he says. "At a government level, I am not very optimistic about the present nor about the future.

"However Chinese people are waking up. People now realise that all the dreams they gave us are just bull."

'Beijing is much prettier'

Human rights groups point to the mass detention of lawyers, the establishment of vast new "re-education" camps in the western region of Xinjiang as part of a crackdown on the country's ethnic Uighur Muslims, the explosion in facial recognition surveillance available to the authorities and on and on the list goes.

Yet for the majority of Chinese people none of this really touches them.

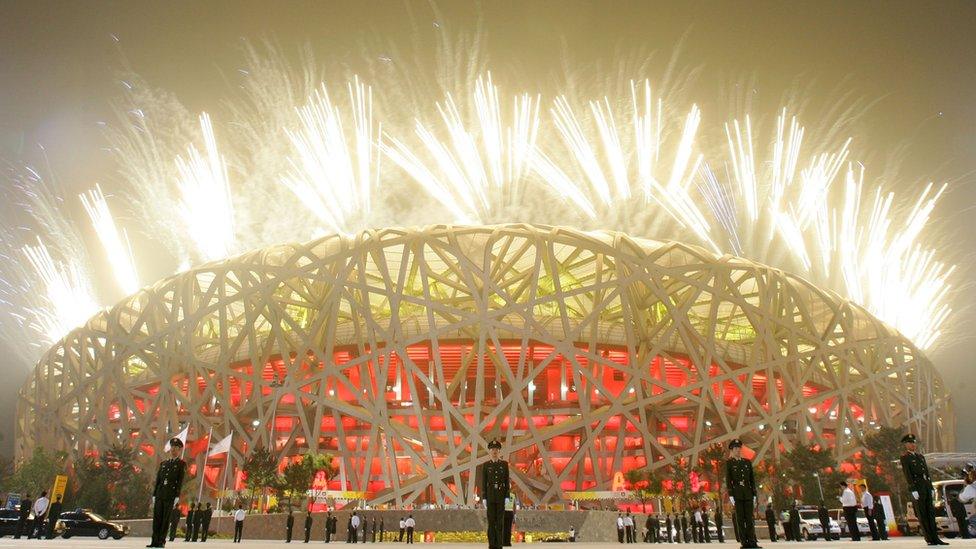

Inside the Birds Nest, 80-year old Cong Ruiying is beaming. She has come to the capital from Jiangsu province with her family.

These days the stadium has a nightly light show reliving the music and feeling of the Games. A visit to the Olympic zone is a must for the thousands of Chinese tourists travelling to Beijing every day.

The Bird's Nest features a daily lights show

Cong Ruiyang didn't get a chance to be here in 2008 and she's excited to have finally arrived.

"It's beautiful," she says as the multi-coloured lasers zoom around.

I ask what she thinks of the city overall.

"It's become prettier and actually much better."

Does she prefer the China of today or 2008? She smiles, has a bit of a laugh and looks at me like I am some kind of nutcase to even ask such a question.

"Of course it's better now," she says.

- Published2 January 2018

- Published24 October 2017

- Published3 August 2018

- Attribution

- Published18 July 2018

- Published15 May 2012