Xi Jinping: Digital 'little red book' tops App Store in China

- Published

China's most popular app over the last few days has been one that's red in face and at heart.

With a scarlet logo reading "study" in Chinese, or "study Xi" as an ingenious pun, the app aims at shaping the nation's minds under Xi Jinping's presidency.

Launched on the first day of the year by the central propaganda department, members of the ruling Communist Party have been required to download and use it on a daily basis.

So have civil servants, state-owned company employees and public school teachers, even those who aren't Party members.

The app, "Study (Xi) Strong Country," started to climb up the rankings in late January and became the most downloaded free app on China's App Store on Tuesday, surpassing some phenomenally big hitters like WeChat and TikTok, known as Weixin and Douyin in the local market, according to mobile analytics firm App Annie.

In a clear sign of Mr Xi's stature and influence, the Communist Party voted in 2017 to commit his philosophy, called "Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era", to its constitution.

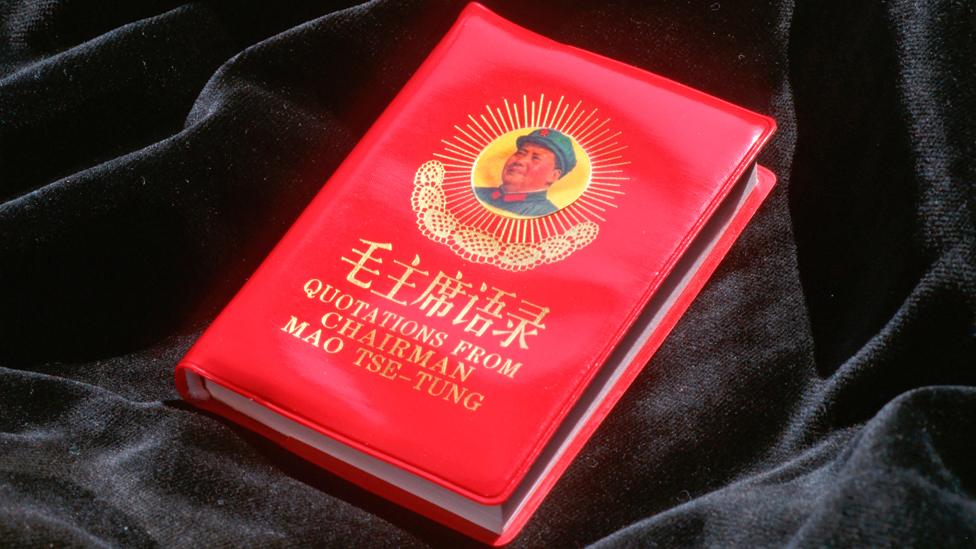

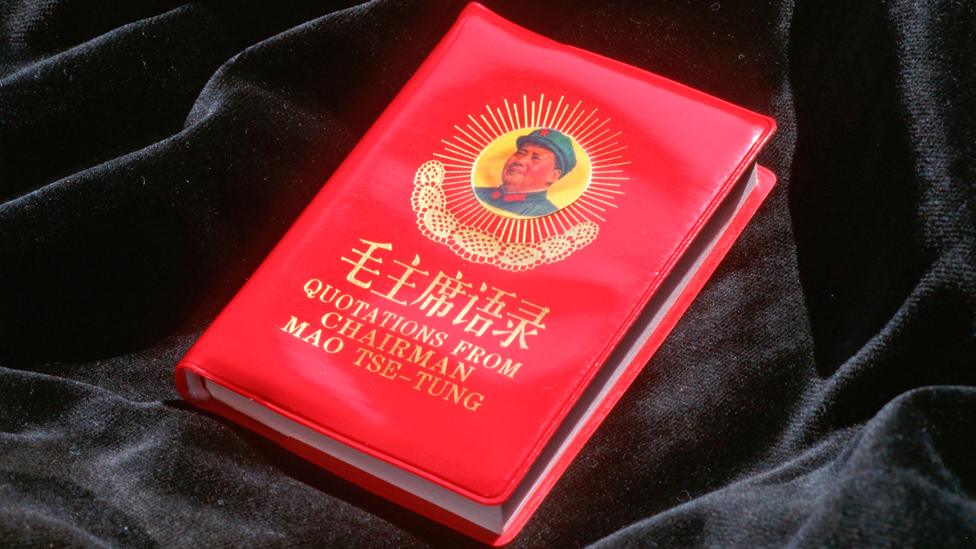

As the most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, President Xi has followed suit to sell his philosophy nationwide. The last ideological product to have swept China was Mao's Little Red Book, more than a billion copies of which have been published.

During China's Cultural Revolution, it was virtually mandatory to own and carry the "little red book." In the Xi era, the modes are smarter, and this will doubtless be seen as a "little red app".

Users of the app are able to learn Xi's thoughts, read state media news, take MOOC online learning courses and earn points based on their usage. These points accumulate and can be used as a point of reference for their employers and ultimately the Communist Party (CCP).

It stands to reason that the influence of online propaganda should be more overwhelming than during the print age, given technological advances and the vast, instant user base. CCP members have more than doubled in number since Mao's era, let alone the other users compelled to sign up who work for government-run institutions.

On China's Twitter-like Weibo, some have complained about the formality of the app, saying it is hollow, slick and a waste of time. If anybody expected games, they would have been disappointed. It is a serious affair.

One Weibo user from Shandong province said she had to earn 66 points per day - which according to a screenshot of the learning record she posted takes around two hours.

The ruling Communist Party, under Mr Xi's leadership, has long been seeking to promote its philosophy through ever-more-innovative formats, as hungry as any media outlet for those elusive millennial audiences. State-owned broadcaster CCTV and a provincial TV channel in central Hunan province launched shows last year that featured Xi quotations and thoughts.

But propaganda has also reinvented itself as WeChat stickers that animate CCP mottos or lines, and a cartoon based on the life of Karl Marx released last month on popular video sites Bilibili and Youku.

The "little red app" doesn't have quite such quirky aspirations, but it's certainly popular nevertheless.

- Published4 October 2018

- Published14 March 2017

- Published26 November 2015

- Published24 October 2017