When did 'die-ins' become a form of protest?

- Published

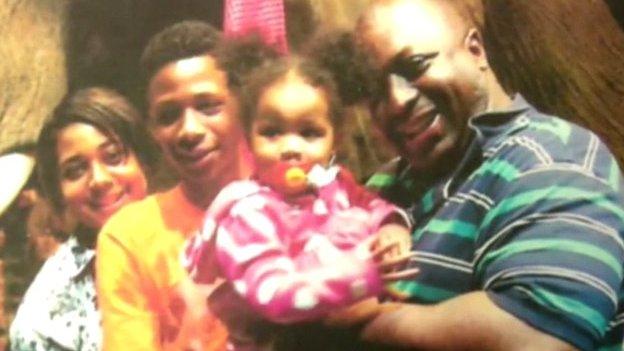

In the wake of the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown, die-ins are being staged across America. But how did die-ins become a form of a protest?

While much of the unrest involved chanting, marching, and in some cases, destruction of property, the die-ins are a vital component of the latest round of protests. On 22 October, students from San Francisco State University Black and Brown Liberation Coalition chanted "black and brown lives matter" and "hands up, don't shoot" on their way to Malcolm X Plaza.

"Then, we will start falling down 'dead' to the ground in rounds," they were instructed on social media. "Our bodies will act as physical reminders of how many black and brown lives are taken from us each day by unnecessary police force."

Many protesters lay down for four and a half minutes to represent the four and a half hours Michael Brown's body lay in the street after he was shot. In several locations, including Apple's flagship store in New York City, hundreds lay in the way of traffic and shoppers.

"I remember lying on the ground for four and a half minutes, being completely silent, everyone else around doing the same, with six helicopters flying overhead," says Grace Cooper, a 19-year-old student who participated in a die-in last week in Boston. "That silence gave you a chance to think about why you're doing it."

Die-ins did not start in this wave of protests. Last year, more than 1,000 cyclists staged a die-in in London to call for road safety. The year before, protesters in that same city held a die-in to protest about Olympic sponsor Dow Chemicals.

Protestors staged a "die-in" in New York when the UK royals were at a basketball game.

Robert Widell, associate professor of history at University of Rhode Island, remembers die-ins happening as far back as the 1980s, during the Aids epidemic. "What we've seen historically is that specific forms of protests draw attention to the kind of thing that's happening," says Prof Widell.

He says wade-ins, in which black people waded into the water of whites-only beaches, along with sit-ins and teach-ins, were popular when public spaces were segregated by Jim Crow laws. The idea is to create an image that makes an impression. "This kind of publicity forces the country to deal with the violence that faces African-Americans," Widell says.

Reporting by Micah Luxen

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published8 December 2014

- Published21 August 2014