The Election Vocabularist pt I

- Published

The history of words we use at election time is often rich and sometimes surprising.

When Ed Miliband apparently wrote a note to himself to be a Happy Warrior in the leaders' debate, he was using a phrase which has a long American political pedigree, and a long English literary pedigree before that.

In 1677, Nathaniel Lee, writer and collaborator of Dryden, wrote a poem celebrating the marriage of the Prince of Orange, later William III, beginning: "Hail, happy Warriour, hail, whose arms have won/ The fairest Jewel in the English Crown."

Wordsworth in 1807 wrote the Character of the Happy Warrior in praise of Horatio Nelson, the hero whose courage and generosity made him "he, that every man in arms would wish to be".

The poem was a favourite of US judge and politician Joseph Proskauer, who is said to have suggested it to Franklin Roosevelt when he proposed Al Smith for presidential candidate at the 1924 Democratic party convention.

"He has a personality that carries to every hearer not only the sincerity but the righteousness of what he says. He is the Happy Warrior of the political battlefield," said Roosevelt of Smith. Since then it has been applied to various Americans, most recently by President Barack Obama to Vice-President Joe Biden.

Happy originally meant lucky, and is related to words like happen and perhaps, suggesting chance. War and warrior came to us through French from an old Germanic word meaning confusion or discord.

When Nick Clegg accused David Cameron of playing a "game of hokey-cokey" over the EU he no doubt had in mind the line "in, out, shake it all about". So had Nigel Farage when he called the row over the leaders' debate "a sort of political hokey-cokey".

A ring dance with this line or something like it has spread around the world. "Hokey-cokey" (often "hokey-pokey", especially in America) is just one name for it.

The version noted by Cecil Sharp in 1909 started: "Here we dance looby loo." It included the line: "Put your right hand in, put your right hand out, Shake your right hand a little, a little, And turn yourself about."

There was already a dance called the hokey-pokey, though it is not clear whether it was part of the shake-it-all-about genre. In 1873, Joaquin Miller's wrote in Life Amongst the Modocs how a prospector who had his camp washed away in a flood "danced a sort of savage hokee-pokee" in despair. And a racehorse called Hokee Pokee is recorded as racing at Wolverhampton in 1832.

Some think there is a relationship to the magician's cry of "hocus-pocus" - recorded by Thomas Ady in 1656. And there's a suggestion that hokey-cokey could even be anti-Catholic, external. In 2008 it was suggested that action should be taken against anyone who used it to taunt Catholics at Scottish football matches. In this theory, hocus-pocus is a corruption of "hoc est corpus meum" - "this is my body" - in the Latin Mass.

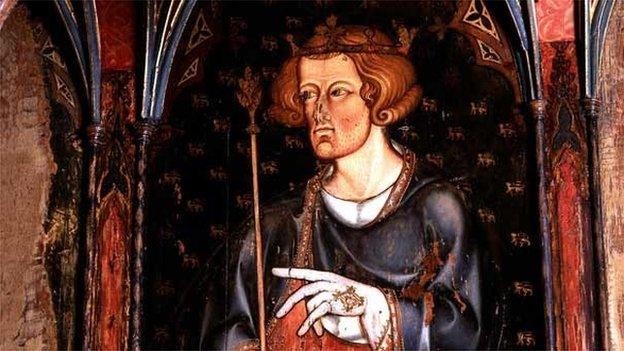

Edward I in 1295 told the sheriffs that MPs must be elected (elegi)

Election - or electio, in Latin - has meant "picking out" for more than 2,000 years. It and its related words come from various forms of the verb eligo, from lego, to choose - made stronger by having e-, or "out", at the beginning.

The word has a special niche in parliamentary history. Edward I's Parliament of 1295 is usually counted as the start of the regular summoning of the commons, as well as lords and prelates.

The writs Edward sent to county sheriffs ordered them not merely to cause the representatives to come to the Parliament (venire facias) as before - but that to cause them to be chosen (elegi facias). And so elections officially entered the language.

In Latin, lego came to mean to pick out the letters on a page, and so "read" - giving us words such as lecture and lectern.

Eligo is a sort of cousin of our word "eclectic" meaning "choosing the bits you like". It also comes from lego, meaning to choose, with "out" at the beginning, but in Greek.

Now, the classical Greek word for "say" is also lego, giving us words such as "dyslexic". But that's not related to lego meaning choose, in either Greek or Latin.

The Vocabularist

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.