What is the legacy of the Paralympic Games?

- Published

- comments

It's exactly one year since the London 2012 Paralympic Games began. Hopes were high for a positive legacy but a charity today says that disabled people are still waiting.

Lord Coe's closing speech at London 2012 drew attention to the Paralympic legacy. "I really genuinely think we have had a seismic effect in shifting public attitudes," he said. "I don't think people will ever see sport the same way again, I don't think they will ever see disability in the same way again."

The charity Scope today suggests a less than seismic shift. In a poll of 1000 disabled people, 81% say that public attitudes haven't improved in the last 12 months - in fact, 22% say they've got worse. The overwhelming majority of this latter group blame "benefit scrounger" rhetoric from politicians and the media.

Another new survey by Leonard Cheshire Disability claims that more than one in five disabled people say that intimidation and abuse prevent them from going out.

This time last year we were watching giant apples, disabled dancers suspended in mid-air doing an umbrella routine and scientist Stephen Hawking, all live from the stadium in an opening ceremony that made people sit up and pay attention. Lest we forget, it felt like disabled people were taking over the UK, with their sports taken seriously, huge crowds in the park and something new and positive in the air.

The Paralympics coverage by Channel 4 went on to win the TV Bafta for best sport and live event, despite strong competition from the BBC.

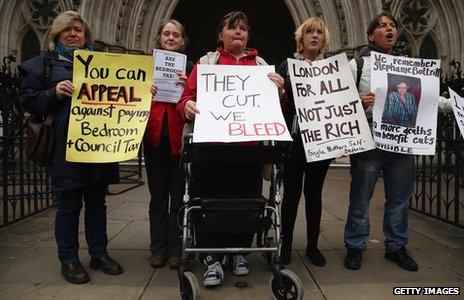

But the games took place against a backdrop of cuts to disability benefits, and a feeling of underlying dissent was apparent from the very start. The opening ceremony featured a choreographed protest symbolising the struggle towards disability rights.

There were protests during the games against the involvement of Atos, the company which at the time ran the government's work capability assessment (WCA) process. This controversial programme determines whether people are fit for work or eligible for disability allowance. The government says it allows those who need help to be better targeted. But disabled campaigners said that WCA was "damaging and distressing". Some athletes reportedly hid lanyards printed with the Atos logo in protest.

Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC) are holding a week's worth of protests on the anniversary. DPAC's Linda Burnip says the legacy is going to become meaningless as benefit cuts begin to kick in and materially affect the lives of disabled people. She hopes that a visit this week to the UK by the United Nations special rapporteur (special representative) on housing, may bring about change. "In October a second rapporteur is meeting with us around the subject of care support funding, WCA and closure of the independent living fund," says Burnip.

The jury's also out on another legacy goal - public transport accessibility. The campaign group Transport For All (TFA) is unhappy that seven stations on the new Crossrail route through London will not be step-free. It's holding a legacy torch relay today along the route of the line, which is still under construction.

The sheen may be wearing off our memory of the Games, but there is a consensus that from a sporting point of view, the event was a runaway success. Elite disability sport is now taken seriously in a way few commentators had expected, and Johnnie Peacock, Ellie Simmonds and David Weir - to name a few - have become household names.

The team behind London 2012 hoped that the Olympic and Paralympic Games would "inspire a generation".

In July, Sebastian Coe called for a 10-year legacy plan and then resigned as the government's Olympic legacy ambassador. He felt that a positive legacy was more likely to happen without him as people assumed he held all responsibility.

At the end of the Games last year, veteran Paralympian Tanni Grey-Thompson urged everyone to keep the momentum up, saying: "You can't wait for someone else to do legacy, you've got to take a bit of responsibility for yourself."

Disabled people are still celebrating the spirit of the Paralympics, Martyn Sibley who co-edits the online magazine Disability Horizons, will soon be travelling in his powered wheelchair from John O'Groats to Land's End, external for the Britain's Personal Best project. He says he's making the journey because he doesn't want the light to go out.

And Alexa Wilson from Wiltshire has seen this kind of do-it-yourself legacy in action. She is mum to 12-year-old Ellie who has autism. She says that in her experience, the Paralympics have given a new and helpful focus to people who want to do something positive for her daughter's school and that Ellie is already benefiting.

"Often in the past people didn't know what to do to help," she says. "They knew they wanted to do something for the local special school and we've had fantastic help before, but now they're coming forward with opportunities for the children to go sailing, for instance.

"Rather than donating some shrubs to the sensory garden which they did the year before last, they're now suggesting doing something sporty - thanks to the Paralympics. That's inclusive and healthy too. It's not like the children only want to wander round the sensory garden all day."

You can follow Ouch on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external, and listen to our monthly talk show