Election 2015: Who won the interview contest on social media?

- Published

The first big set piece of the general election campaign generated tens of thousands of tweets under just one hashtag - but what do the numbers mean?

#BattleForNumber10 shot to the top of Twitter's list of UK and worldwide trends just as Thursday's duelling interview session began, and by the time the broadcast ended more than 260,000 points, zingers, hastily Photoshopped memes and wry observations had been posted - with similarly big numbers under related hashtags.

The Prime Minister went first and as he faced a typical Jeremy Paxman grilling about everything from zero-hours contracts to his friendship with Jeremy Clarkson, many commenters wondered whether he might have been better off debating his opposite number.

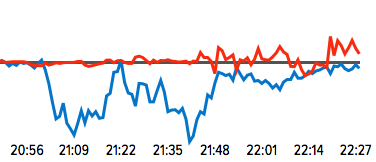

The Centre for the Analysis of Social Media at think tank Demos, Ipsos Mori and the University of Sussex ran an online tracker during the debate, external, separating tweets into cheers and boos and scoring the candidates accordingly. By that measure, David Cameron's ratings plummeted at the start before recovering somewhat during the audience questioning.

Ed Miliband, who faced audience questioning first, traced a somewhat better trend line while answering questions about economic policy and Labour's previous performance in government - he ended the debate with cheers outweighing boos 53-47.

A snapshot of the Demos/Ipsos/Sussex trend line taken just after the debate.

Demos' Carl Miller called the clash one of the biggest digital moments in British political history, with more than 2,700 tweets per minute, far more than during recent debates over Scottish independence or Europe.

"This is the first time we've seen in our analysis a politician emerge with more cheers than boos overall," Miller said of Miliband.

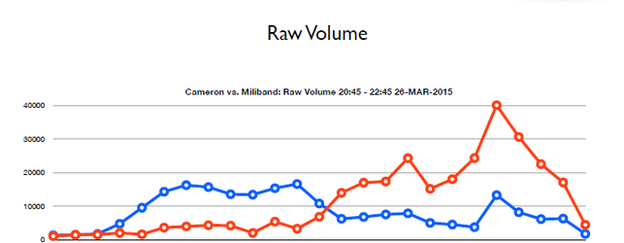

A separate analysis of half a million tweets conducted by social media sentiment firm TheySay, which uses software developed at the University of Oxford, also found that the Labour leader won by a small margin, with reaction to Miliband slightly positive and Cameron shading slightly negative. TheySay also tracks emotional responses such as fear, uncertainty, and humour.

"In general, Miliband's signals were more volatile than those for Cameron," says TheySay co-founder Karo Moilanen. "Miliband's sentiment profile is more jagged - a sign of more extreme polarisation."

"Given that doubt, anger, agitation, and fear all increased towards the end around Miliband, his passionate plea was highly emotional. Miliband's impressive performance generated more traffic than Cameron's first round - in a typical situation, the prime minister dominates in social media volume."

The Twitter analysis contrasts with an early ICM opinion poll for the Guardian which suggested Cameron outclassed Miliband - 54% of of the 1,123 viewers surveyed saying they thought the PM "won".

Raw Twitter volume as measured by TheySay

Social media election?

It's early days, but commentators are already calling this the first social media election. Of course, we've heard this before - five years ago to be exact, and it didn't exactly pan out, external. That said, there are definite differences this time. More politicians and voters use social media, and the parties are taking social media seriously - spending thousands on Facebook advertising.

One key to analysing social media will be a host of companies and organisations involved in "sentiment analysis" - simply put, figuring out what people mean by the mass of messages flowing through their social media accounts.

This is about more than just numbers. For example, if Facebook chatter translated directly into votes, UKIP and Nigel Farage would be sitting in second place, while the Liberal Democrats would be not the third, fourth or even fifth party - they'd slip down to sixth behind the SNP and Greens. (BBC Trending covered the statistics earlier this week, external). It's highly unlikely that those results will translate directly to electoral success or failure however.

That's where sentiment analysis comes in. Although it has its critics, external and is by no means a perfect science, it might be able to add something to our understanding of the numbers. Twitter is a public platform, which makes it easier to analyse, particularly in real time. But Facebook, a more closed platform, is much more popular and probably a better gauge of a wider range of opinion across the country.

Which means Thursday's analysis is interesting - but far from conclusive. To find out how the interviews might really affect the election you'll probably have to do something very old-fashioned: over the next couple of days, keep an eye on the polls.

Blog by Mike Wendling, external

Next story: The viral speech against a school's grading system

Or maybe you'd like to watch: Why did this journalist lose her job?

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.