What makes a 'social media election'?

- Published

Commentators are already arguing about whether it was a "social media election" - but what does that term really mean?

Depending on who you pay attention to, this was either the UK's first "social media election" - or it wasn't, external.

Of course, maybe 2010 was the first social media election, external - or maybe it wasn't, and maybe the next one won't be either, external.

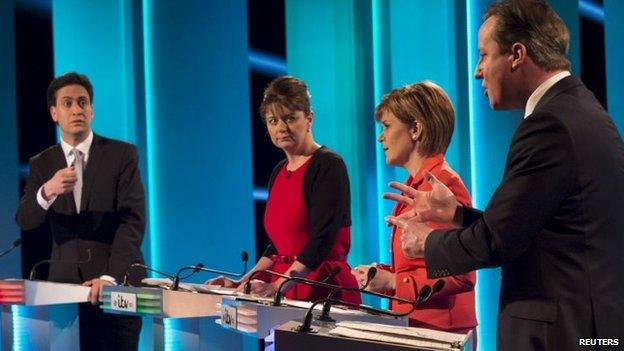

The truth is, for all the millions of tweets and Facebook posts, traditional media still dominates in the UK. Twitter users sent 1.5m messages about the 3 April leaders' debate.

That's a big number - but still less than a fifth of the total number of people who watched the TV broadcast.

So has this been a "social media election"? When all the votes are tallied and the results have come in, here are the things to look out for in order to answer that question.

Did social media mobilise the age group least likely to vote?

When journalists talk about a "social media election" they tend to have one thing in mind - did something happen online which influenced voters and changed the course of the campaign?

There have been various attempts to create such a moment. One was Russell Brand's interview with Labour leader Ed Miliband, which has been watched more than 1m times on YouTube, external.

David Cameron was moved to respond to it - by saying he didn't have time to "hang out" with celebrities, external. And earlier this week Brand called on most voters to back Labour.

The Brand interview was far from the only such viral moment created by parties and their supporters. For example there were the competing #Milifandom and #Cameronettes hashtags ... Nick Clegg's "gangster" fashion ... and a host of celebrity memes, attacks and counterattacks.

If one thing unites all of these things it's their potential appeal to the age group least likely to vote, external.

"If turnout goes up among young people, it may be some indication that social media did play a part in the campaign," says Adam Parker, founder of the social media analytics platform Lissted, external.

According to one survey taken before the election, a third of young people said that social media would influence their vote, external.

What impact would that have? The conventional wisdom says that more young people voting would benefit Labour. But like everything else in this election, it's not that simple.

Carl Miller, research director of the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media at the think tank Demos, says voting patterns among young people - particularly first-time voters with no ballot box history to look back on - are becoming less predictable.

UKIP has a highly organised social media campaign and the SNP, as we've reported before, punches well above its weight online.

"When 10,000 votes in a dozen swing marginal seats could dictate who the next prime minister is, of course social media could be decisive," says Miller.

"But so could television, or leafleting - this election is so close, anything could be decisive."

The social media numbers are huge - but that means very little

The numbers of people talking about the general election campaign online are greater than ever before - but of course, that's not surprising in a world where more people are online and than ever before.

Party hashtags and leader names have been used millions of times, with almost 500,000 uses of one hashtag, #GE2015,, external just in the past week alone.

Parker warns against placing too much emphasis on raw numbers - such as the number of tweets using a particular leader's name.

"There's a lot of nuance and complexity, more than ever before," he says. "There are so many different issues, many of which go right down to the local level. How will the SNP influence Labour? How will UKIP impact Conservatives? Will Tories tactically vote Liberal Democrat in Sheffield?

"There are just so many different possibilities and issues. A number tells you nothing."

"The best way of looking at the effect of social media isn't actually looking at social media itself," says Miller. "You really have to go back to conventional research."

It's only when follow-up surveys ask people questions such as whether social media made them more likely to vote, whether it influenced their vote or made them feel more engaged, that we'll have any real inkling if this was a "social media election" - no matter how many millions of tweets were sent.

Did social media mobilise political volunteers?

Of course, journalists are hard-wired to look for moments and events - in other words, news.

And a lot of attention has also been paid to how undecided voters might be swayed.

But there's a less obvious way in which social media is being used in this campaign - to rally the troops, organise volunteers and get out the vote. And again, because this election promises to be so close, those efforts might prove decisive.

Miller says the parties have all pursued this strategy, and that they've taken a cue from US elections. The Obama campaigns of 2008 and 2012 "showed that you could do that difficult alchemy of turning likes and tweets to volunteers, donations and votes," he says.

For example the the Conservatives' "Team2015" campaign has tried to mobilise supporters and reach beyond party members - to find more people willing to make donations or knock on doors.

Will those efforts give the Tories an edge over the other parties, each with their own digitally assisted ground-game tactics? That's another key question that probably won't be answered on the night.

Why we might never know the answer

Of course, it could be that the biggest impact is yet to come. During the television debates we saw claims and counterclaims washing across Twitter like so many waves on a very blustery beach.

With the polls predicting a close result and a high chance of negotiation and deals, the political messages being sent immediately after the polls close on Thursday will be key.

It's safe to assume that politicians, activists and meme-makers will be jockeying for position and the political tussle will continue on TV, radio, in newspapers - but most immediately, online.

There is no settled consensus on what strategies work online, as there is with other political tools such as polling and focus groups, Miller says.

That means that while, for instance, we know that the Conservatives have been spending a lot of money on Facebook, and UKIP's efforts have to some degree paid off online, the fine details of party social media strategy are still hard to come by and hard to measure.

So we might never know quite how influential social media was in shifting the outcome of Thursday's poll.

Elections are one-time events - they can't be rerun with the social media taken out. Without any hard proof either way it's probably folly to declare this a "social media election" (or the opposite).

But that won't stop pundits trying to do so after the contest is over - or even before.

Next story: The Costco heir who became a voice for Baltimore

Follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external.