The rise and rise of fake news

- Published

The deliberate making up of news stories to fool or entertain is nothing new. But the arrival of social media has meant real and fictional stories are now presented in such a similar way that it can sometimes be difficult to tell the two apart.

While the internet has enabled the sharing of knowledge in ways that previous generations could only have dreamed of, it has also provided ample proof of the line, often attributed to Winston Churchill, that "A lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get its pants on".

So with research, external suggesting an increasing proportion of US adults are getting their news from social media, it's likely that more and more of us are seeing - and believing - information that is not just inaccurate, but totally made up.

There are hundreds of fake news websites out there, from those which deliberately imitate real life newspapers, to government propaganda sites, and even those which tread the line between satire and plain misinformation.

A US election story untainted by fact

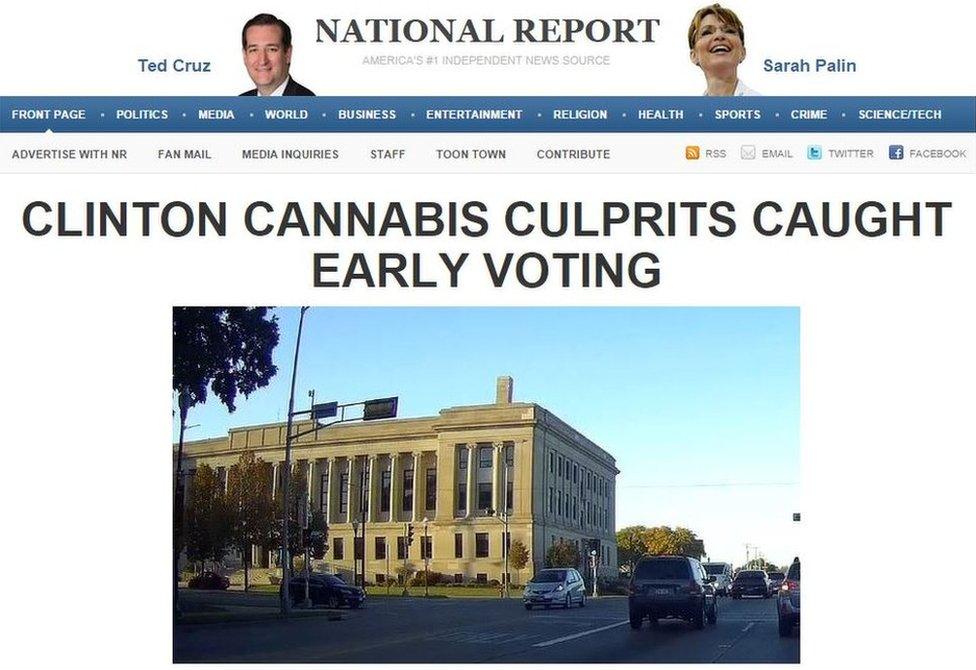

One of them is The National Report, external which advertises itself as "America's Number 1 Independent News Source", and which was set up by Allen Montgomery (not his real name).

"There are times when it feels like a drug," Montgomery told BBC Trending.

"There are highs that you get from watching traffic spikes and kind of baiting people into the story. I just find it to be a lot of fun."

One of The National Report's biggest ever stories was a scare about a US town being cordoned off with a deadly disease, external, and as Montgomery explains they've mastered the art of getting people to read and share their fake news offering.

"Obviously the headline is key, and the domain name itself is very much a part of the formula - you need to have a fake news site that looks legitimate as can be," Montgomery says.

"Beyond the headline and the first couple of paragraphs people totally stop reading, so as long as the first two or three paragraphs sound like legitimate news then you can do whatever you want at the end of the story and make it ridiculous."

But why go to such trouble? The answer is there is big money to be made from sites by The National Report which host web advertising, and these potentially huge rewards entice website owners to move away from funny satirical jokes and towards more believable content because it is likely to be more widely shared.

"We've had stories that have made $10,000 (about £8,100). When we really tap in to something and get it to go big then we're talking about in the thousands of dollars that are made per story," Montgomery says.

Trick or treat?

But how much should be worried by fooled by sites that set out to get fake news stories up and running?

Brooke Binkowski from Snopes, external, one of the largest fact checking websites which fights online misinformation, believes that while individual fake news stories may not be dangerous their potential to cause damage becomes more powerful over time and when considered in the aggregate.

"There's a lot of confirmation bias," she says. "A lot of people want proof that their world view is the accurate and appropriate one."

And that idea of reinforcing people's beliefs and falsely confirming their prejudices is something that Allen Montgomery says his fake news site actively tries to exploit.

"We're constantly trying to tune into feelings that we think that people already have or want to have," he says.

"Recently we did a story about Hillary Clinton being fed the answers prior to the debate. There was already some low level chatter about that having happened - it was all fake - but that sort of headline gets into the right wing bubble and they run with it."

Buzzfeed's Craig Silverman, external, who heads a team looking into the effects of fake news, explains just how easily fake news can end up being reported as true by the mainstream media.

"A fake news website might publish a hoax, then because it's getting social attention another site might pick it up, write that story as though it's true and may not link back to the original fake news website," Silverman says.

"From there it's a chain reaction until at some point a journalist at a largely credible outlet might see it and quickly write something up, because many journalists are trying to write as many stories as possible and write stories that get traffic and social attention. The incentive is towards producing more and checking less."

Not the naked truth

And as Anthony Adornato, assistant Professor of Journalism at Ithaca College in New York explains journalists are not only under increasing pressure but in many cases are also not being given sufficient guidance on how to properly verify stories.

"The policies in newsrooms haven't caught up with the practice," Adornato says.

"Its commonplace that news outlets are relying on content that folks have shared, but not every newsroom has a policy regarding how to verify and authenticate this information."

A recent study, external of local TV stations in the US conducted by Adornato revealed that that nearly 40% of their editorial policies did not include any guidelines on how to verify information from social media, yet news managers at the TV stations admitted that at least a third of their news bulletins had reported information from social media that later was revealed to be false or inaccurate.

So with the fake news floodgates now wide open, has the battle to contain it already been lost?

Allen Montgomery says Facebook has taken steps to reduce the impact of fake sites like his own.

"We were specifically targeted by the Facebook changes in their news feed algorithm. They've drowned out our stories from being shared and from being liked, and I have no doubt that they are doing the same to other fake news sites. Really though, if there's money to be made - and there is - you just have to get more creative."

Montgomery says he now has nine fake news sites around which he moves content to try to beat Facebook censoring.

So if fake news sites aren't going away, Buzzfeed's Craig Silverman says that more needs to be done to ensure that people aren't duped by them.

"Journalists need to get training so that they can quickly spot fakes, and people in school should learn how to read things critically online - they should learn how to research and check multiple sources online."

Listen to a special edition of BBC Trending on fake news on the BBC World Service.

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.