Solutions that can stop fake news spreading

- Published

There may be actual solutions to the spread of fake news.

Fake news - from false celebrity gossip to the fabricated story of Pope Francis endorsing Donald Trump - became a huge issue during the US election campaign. Those who peddled falsehoods were motivated sometimes by profit and sometimes by politics.

British parliamentarians are launching a committee to look at the problem. But globally, there are various methods being offered to fix it.

The team behind BBC World Hacks - our news solutions-focussed journalism unit - has been looking into some of the most promising potential solutions.

Humans check the most suspect stories

Facebook, which came under heavy criticism for allowing fake news to be circulated during the election period, have taken steps to offer combat the issue.

One of those steps is the enlisting of the International Fact Checking Network (IFCN), a branch of the Florida-based journalism think tank Poynter, external. Facebook users in the US and Germany can now flag articles they think are deliberately false, these will then go to third-party fact checkers signed up with the IFCN.

Those fact checkers come from media organisations like the Washington Post and websites such as the urban legend debunking site Snopes.com, external.

The third-party fact checkers, says IFCN director Alexios Mantzarlis "look at the stories that users have flagged as fake and if they fact check them and tag them as false, these stories then get a disputed tag that stays with them across the social network."

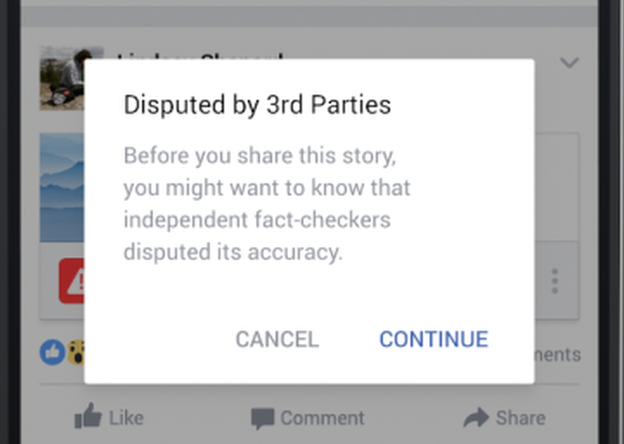

Another warning appears if users try to share the story, although Facebook doesn't prevent such sharing or delete the fake news story. The "fake" tag will however negatively impact the story's score in Facebook's algorithm, meaning that fewer people will see it pop up in their news feeds.

Mantzarlis says there is as of yet no firm evidence that this actually stops fake news spreading on a large scale, and there are questions over how sustainable the programme might be. Facebook is not paying the IFCN members to provide fact-checking services. There's also nothing stopping the fake news from being posted and spread in the first place - and perhaps quite widely before being tagged.

"There is a lag, so until and unless a story is flagged as false that story does continue to spread on the social network," says Mantzarlis.

A screenshot of how Facebook's fact-checking system appears to users in the US and Germany

Humans flag whole sites as fakes

In 2009, Le Monde, external, one of the biggest French newspapers, set up a fact-checking unit called Les Decodeurs, external (The Decoders). Increasingly the unit is turning its attention to fake news, and they've devised a web extension called Decodex.

"You just put it on your browser and then when you come to a fake news site you get a pop up appearing saying 'warning this is a fake news site'," says Samuel Laurent, editor of Les Decodeurs. "If you click on the tool you will have access to a little paper describing the website and saying why we think it's not trustworthy."

The extension is linked to a database that Les Decodeurs has compiled which ranks sites as "fake", "real" or "satire".

But there are several hurdles which likely prevent a relatively simple piece of software from being the silver bullet for fake news. Users firstly have to be aware of the problem of false stories. They have to know about the extension and be concerned enough to download it. And they have to trust Le Monde journalists and the paper's centre-left perspective.

"We know that we won't convince everyone and we know that fake news readers already think we are the fake news," Laurent says. "Our goal is to just provide this tool for people who are really sceptical or who just don't know who to trust.

"People who have already fallen into the fake news vortex, it's too late for them."

Use algorithms to fight algorithms

Algorithms are part of what spreads fake news - because juicy yet false stories which become popular can be pushed out to new eyeballs by the software that runs social networks. But some programmers think computer code could also be part of the solution.

"From an algorithmic perspective it's possible for social media sites to recognise that website was only created two weeks ago, therefore it's probably likely that this is a less trustworthy site," says Claire Wardle of journalism non-profit First Draft News.

First Draft, external is working with Google and Facebook to explore whether they could incorporate code to stop the spread of fake news. Wardle is adamant that tweaking algorithms is not like censorship.

"I'm talking about a bit like a spam folder in your email, those emails still sit there, but you have to go to your spam folder to look for it," she says.

But human language and news stories are complicated in ways that computers have difficulty dealing with, and any automated method of fact checking risks reflecting the biases of the programmers who created it.

"There are some very smart people looking at automated solutions now, around automated fact checking, which can get up to about 80% accurate," Wardle says. "I would argue we are always going to need human eyes at the very end to say 'hang on, have we got entirely duped'… we want a combination of algorithms and human experience."

Hear the full story on World Hacks, from the BBC World Service.

Don't miss BBC Trending's story The rise and rise of fake news

'Pizzagate': The fake story that shows how conspiracy theories spread

A completely made-up story about Pope Francis endorsing Donald Trump was one of the most widely shared pieces of fake news during the US election

Teach people how to spot fake news themselves

The previous solutions are technical fixes, but Bill Dodd has taken a different tack. His proposal would incorporate digital literacy into school curriculums.

"We already have a curriculum right now that teaches critical thinking skills but it hasn't kept up with the digital age," says Dodd, a Democratic lawmakers who has introduced a bill in the California state senate.

Senator Dodd admits not all the detail has yet been worked out, and it it would be the job of the California Board of Education to update the curriculum, but he has some of what might be included, including "trying to discern what the reputation of different sources are.

"If you are dealing with the BBC or the New York Times, chances are you don't have to go any further, but if you are dealing with some unnamed source, you are going to have to go in a little deeper to determine whether or not that's fact or fiction," he says.

And of course, his solution would take years to implement, and would apply to just one state in one country.

"There's so much news coming at kids, and many adults have this as well, but you got to start somewhere," Dodd says.

More from BBC Trending

Visit the Trending Facebook page, external

Stop the creation of fake news in the first place

During the US election, many fake news stories were written not by politically motivated Donald Trump supporters, but by people looking to make some quick cash. And so one way to stop such output would be to eliminate the financial incentives that make fake news profitable.

"To make any decent money, and a lot of the fake news sites do make decent money, you need to start serving millions of ads," says Cliff Lampe, an associate professor at the University of Michigan, "which is why the viral content market has been so important over the last few years."

In November, Google and Facebook announced moves to restrict advertisements on fake news stories, external.

But fake news producers, like others making content designed to go viral, are quick to adapt to platform rule changes.

"I think this will work for the moment, but I believe that people are going to be able to come up with a workaround and be able to manipulate that attention market in the future," Lampe says.

In addition to removing the carrot, there's some big sticks being considered. In Germany, for instance, lawmakers are even proposing criminalising people who post fake news, external.

Reporting by Harriet Noble and Charlotte Prichard

Blog by Mike Wendling, external

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.

- Published27 April 2016