Election 2017: Was it Facebook wot swung it?

- Published

Could stirrings of the UK general election upheaval be seen ahead of time - on social networks?

If you were surprised by the general election result, particularly the relative gains made by Labour and the worse-than-predicted Conservative performance, you probably weren't keeping a close eye on Facebook.

There was a sharp distinction between Tory and Labour styles when it came to social media. The Conservative focus seemed to be sharp, paid-for attack ads. Labour's presence was much more organic, and perhaps more effective with it.

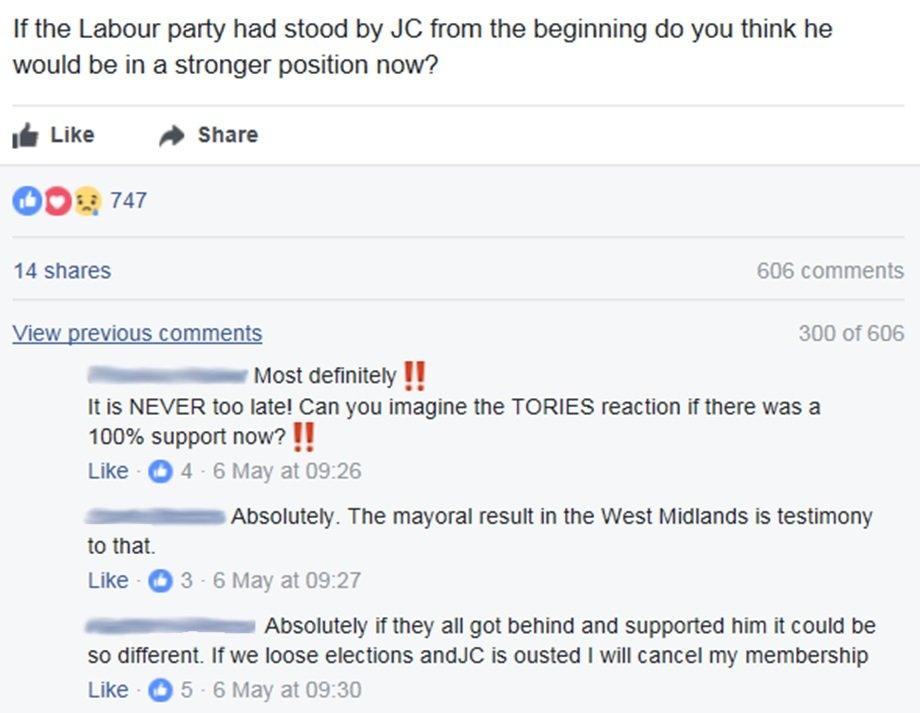

The chatter was happening in big groups - many of them filled with Jeremy Corbyn's most dedicated supporters, and closed to the general public. It was reflected in lists of most-shared stories, external, which were dominated by material sympathetic to Labour and hostile towards Theresa May's Conservatives.

Of course, we can't be sure of how social media shares shape actual voting - and there isn't yet any hard evidence that what people saw on Facebook or any other social network was the decisive factor that swayed huge numbers of votes. We'll have to wait days, weeks or longer for a full analysis to emerge. But what was clear online was a distinct surge in pro-Corbyn enthusiasm, in contrast with a professional and increasingly microtargeted Conservative advertising strategy.

Over the course of the campaign, BBC Trending gained an insight into the minds of some of the most passionate voters by delving into filter bubbles - tight online communities created by algorithms and the way we all use social media.

One of the strongest and most active filter bubbles was the one filled with "Corbynistas". There are hundreds of pages and groups, external devoted to the Labour leader. They have names like "We support Jeremy Corbyn, external", a Facebook group that has more than 55,000 members, more than 15,000 of which were added in the last few weeks.

Some of the groups were closed - Facebook users need to apply for entry, which frequently involves vetting a user's political views.

The purpose of them is to boost their man and their party, spread pro-Labour news, and bash the Conservatives, particularly the prime minister.

They're often fuelled by viral videos from groups such as Momentum - the pro-Corbyn organisation which says a quarter of UK Facebook users saw one of its videos during the election campaign, external.

Because posts in these private groups are difficult to view, they can often fly under the radar, particularly when compared to trends on open platforms like Twitter.

The enthusiasm for Corbyn inside these groups seemed very similar to the social media pattern we've seen for other, very different politicians around the world. There were - and indeed still are - thousands of Facebook groups devoted to Donald Trump, for example, filled with die-hard loyalists angry with the establishment.

In the wake of Trump's election, much attention was given to "fake news" - and the lightning-fast spread of outright false stories online is a relatively new and troubling phenomenon. But in many of these groups - both the pro-Corbyn and pro-Trump ones - outright fake news isn't the bulk of the material shared. Instead, hyper-partisan stories, polls and memes help to solidify opinion and rally the troops.

It's not that the Conservatives were absent from Facebook - far from it. But the "True Blue" filter bubbles we saw seemed smaller in scale.

Instead the most notable aspect of the Conservative presence on Facebook was paid advertisements. The "strong and stable" message was drilled in from the outset and Tory ads often took an attacking tone. Labour and other parties also paid for advertisements, but based on the limited samples we managed to crowdsource - with help from our colleagues at BBC Newsnight, local radio and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism - they seemed lesser in scale.

In the waning days of the campaign, we saw an increasingly granular approach by the Conservatives on Facebook, with the party targeting very specific groups of people using very specific local issues. That again was reminiscent of US social media strategies and particularly the Trump campaign, which used thousands of different versions of Facebook ads, external to reach different groups of voters.

But, online at least, many of the messages coming from the Conservatives seemed not to gain viral traction.

An example of a hyper-targeted Conservative advert seen in Derby North. Labour won the seat

A week before the election I spoke to Andrew Bleeker of Bully Pulpit Interactive, a top digital strategist on former US President Barack Obama's presidential campaigns. Particularly important, Bleeker said, is the "share" - when users take stories they see in groups and push them to their own personal circles.

When I outlined the general election social media landscape for him, he said that the Conservatives had reason to worry.

"There's certainly some demographics which are more likely to share content, younger demographics, more partisan demographics," he told me. "But nonetheless, money and advertisements can't buy organic interest.

"On Facebook it's particularly difficult to buy attention, you really have to earn attention, and advertisements give you the chance to do that, but ultimately it's the quality of your content, the engagement with your content, that really breaks through,"

"You can't buy shares. You can buy exposure to content, but shares have to come from genuine enthusiasm," he said.

Filter bubbles can rally support and indicate hidden surges, but they can also obscure reality if you're inside of one.

In recent weeks we've been in a pro-Scottish independence hangout in Glasgow where drinkers were overwhelmingly positive about the SNP's prospects, and Facebook groups filled with true-blue Conservatives pining after the days of huge Tory majorities under Margaret Thatcher. Both groups will be devastated by the result.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this content.

How can you pop your filter bubble?

It bears repeating: Facebook certainly wasn't the only factor and probably not the main one which led to the election result. The general consensus is that the Conservatives ran a rather poor "offline" campaign. Indeed, it could alternatively be suggested that their microtargeting advertising strategy was actually effective, and stemmed Conservative losses in some areas, turning an utter disaster into a mere failure.

It may well be that much of the noise on social media was simply reflecting, rather than influencing, public opinion. Again, we'll learn much more about the result in the coming days.

But one lesson from this general election for pundits and parties is clear: ignore Facebook at your peril.

Blog by Mike Wendling, external

Additional reporting by Sam Bright

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.