US net neutrality vote: a brief guide

- Published

What is net neutrality and how could it affect you?

The US communications regulator has voted to weaken the rules that govern net neutrality in the country.

It's a decision that has enflamed passions, with many of the biggest names in tech opposing the change.

What is net neutrality?

Net neutrality is the principle that an internet service provider (ISP) should give consumers equal access to all legal content regardless of its source.

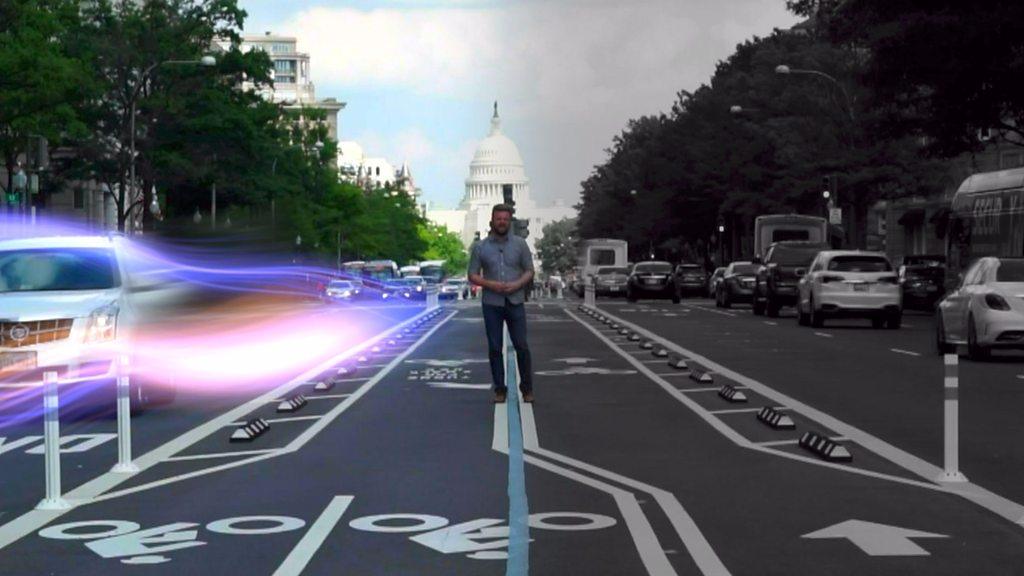

To put it another way, if the networks which form the bedrock of the internet were a motorway, then under net neutrality, there wouldn't be fast lanes for cars and slow lanes for lorries. Motorists wouldn't be able to pay to use a faster route. All data regardless of its size, is on a level playing field.

In practice what this means is that ISPs - the biggest ones in the US include Comcast, Charter and AT&T - cannot block content, speed up or slow down data from particular websites because they have been paid to do so. And they can't give preferential treatment to their own content at the expense of their competitors.

Memes like this one were circulated ahead of protests held earlier in the year

Proponents of net neutrality say it's a matter of fairness, that the previous system limited censorship and ensured that large ISPs couldn't unfairly choke off other content providers. But opponents say it amounted to an undue restriction on business, that regulation stifled investment in new technology, and that net neutrality laws were outdated.

What does the vote mean?

The US Federal Communications Commission (FCC), with the support of the Obama administration, last revised net neutrality regulations in 2015, after an extensive campaign by activist groups and tech companies. Those rules put ISPs in the same category as other telecommunication companies.

But President Trump is a vocal critic of the measures, and appointed a net neutrality opponent, former commissioner Ajit Pai, to chair the FCC at the beginning of this year.

Pai has said he fears that internet service providers are not investing in critical infrastructure, external such as connections to low income or rural households because the net neutrality rules prevent them from making money from their investments.

Ajit Pai, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, has been a prominent critic of net neutrality regulations

Under the new rules, broadband providers will be able to give preferential treatment to some services' data and to charge consumers more to access certain content.

But the ISPs will have to publicly disclose these practices. If they fail to do so properly, another regulator - the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) - will have the power to hold them to account.

One of the most outspoken critics of this system has been British comedian John Oliver, the presenter of Last Week Tonight. In May, he asked his audience to post complaints to the FCC's site.

Some reports claimed that so many people did so that the FCC's website crashed because of the influx, but the commission later said the crash was due to a denial of service attack by hackers., external

In any event, it did not change Pai's mind or prevent the new rules being passed by three votes to two.

John Oliver has released YouTube films to continue his campaign in support of net neutrality

What next?

Democrats have vowed to try to overturn the proposal.

New York's attorney general Eric Schneiderman has said he will lead a lawsuit challenging the FCC's decision.

He has accused the watchdog of failing to investigate possible abuse of the public commenting process. He said as many as two million identities, some of dead New Yorkers, were used to post comments to the FCC website.

Other net neutrality supporters have said they plan legal challenges of their own.

Washington's governor has also suggested that his state will take its own steps to protect net neutrality.

But Pai has proposed that states be blocked from legislating on the matter at a local level.

WATCH: What do people know about net neutrality?

ISPs will be closely watched to see how they take advantage of the new system.

One of the US' biggest providers, Comcast, has suggested there will not be as big a break with the past as some fear.

"Despite repeated distortions and biased information, as well as misguided, inaccurate attacks from detractors, our internet service is not going to change," it said in a statement.

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, and find us on Facebook. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.

- Published14 December 2017

- Published14 December 2017

- Published14 December 2017