Is Russia trying to sway the European elections?

- Published

EU officials say Russia is using disinformation to influence the outcome of this week's European Parliament elections. How seriously should their warnings be taken?

"Winter isn't the only thing that's coming - so is the risk of interference in our elections," said Sir Julian King, the EU's commissioner for security, in a press conference late last year.

Their primary suspect is Russia. EU officials say the Kremlin has for years been using disinformation to sow discord and confusion across Europe, while undermining voters' trust in the European Union and its democracies.

Russia flatly denies such accusations, calling them "completely false" and "unsubstantiated". But some commentators believe voters' discontent with the EU - the very thing Moscow is accused of stoking - should not be pinned on foreign actors, but rather on domestic politics.

You may also be interested in:

What evidence is there of Russian meddling?

For many people, phrases like "disinformation" and "fake news" only came on to the radar after the 2016 US Presidential elections where, according to US intelligence agencies, Russia covertly acted to influence the result. Moscow has called the allegation "absurd".

Russia was accused of meddling in the US Presidential election in aid of Donald Trump

But officials in Brussels have been taking action against perceived Russian disinformation since at least 2015, when the East Stratcom Task Force was created. It's a unit of 15 people whose mission is to identify and expose any attempts by the Kremlin to mislead and confuse EU citizens.

Giles Portman, who heads the task force, told BBC Trending: "The evidence is being compiled for several years now that Russia has been seeking to influence European democratic processes.

"Attempts have been made to hack and leak, or to denigrate particular politicians, or to misrepresent certain policies. The best way [for Russia] to strengthen itself is to weaken its opponent."

Hear more on this story on the Trending podcast from the BBC World Service: Download now

Russian President Vladimir Putin and French President Emmanuel Macron - pictured here at the 2018 World Cup final

As an example, he cites the 2017 elections for the German Parliament, where right-wing nationalists were allegedly endorsed by Russia.

And during French presidential elections in the same year, Kremlin-funded media outlets were accused of "spreading falsehoods" throughout the electoral campaign. There were also suggestions Russia was involved in a last-minute hack of emails from Emmanuel Macron's campaign.

But what about these European elections specifically?

Officials admit that there is currently little evidence of large-scale attempts to spread disinformation directly related to this week's vote.

"From what we've seen of the European election campaign so far, it looks at the moment less sensational than some of the attempts we've seen [in the past]," says Giles Portman. "What we can see at the moment is this continuation of a message that Europe is collapsing, that the elites aren't paying attention to ordinary people, and that Europe's values and identities are under threat."

But the elections have featured prominently in media outlets funded by the Kremlin, including broadcaster RT and the Sputnik news agency.

"They have been picking up the theme consistently over the past few months," says Olga Robinson, who tracks disinformation for BBC Monitoring. "They do seem to be pushing slightly anti-establishment messages."

Some of those messages dovetail with those being put out by anti-EU, populist, and anti-establishment parties that have been gaining ground across Europe in recent years. Polls suggest, external these parties are likely to increase their number of seats in the European Parliament.

Polls suggest populist and Eurosceptic groups will make gains in the European elections

That being the case, how can the EU guarantee that its efforts to tackle Russian disinformation don't instead interfere with legitimate democratic debate?

"We in no way suggest that we are trying to tell people what to believe, how to vote, or interfere in people's right to hold whatever opinion they may wish to hold," says Portman. "We're just questioning the manipulation of the debate and saying that people's opinions are best based on facts."

How seriously is the EU taking this?

The European Commission, the EU's executive arm, says disinformation is part of Russia's military strategy and that Moscow spends up to €1.1bn (£960m) on pro-Kremlin media - a huge sum compared to the East Stratcom Task Force budget of €3m (£2.6m) to be spent by the end of 2020.

The task force runs a database, external open to the public, where it lists and debunks news articles published by the Russian media that, according to its analysis, contain falsehoods and pro-Kremlin disinformation messages. To date, it has compiled more than 4,500 cases. They also publish a weekly newsletter with some of its findings.

Although the task force now focuses solely on Russian media outlets with links to the Kremlin, it came under fire, external in 2018 for listing articles published by Dutch media outlets as examples of disinformation.

At the time, it was accused of trying to stifle media freedom and, faced the prospect of legal action, external. In response the task force backtracked and removed the three articles, external from its database.

However, the unit is just a small part of the EU's broader "action plan against disinformation, external", unveiled in December last year.

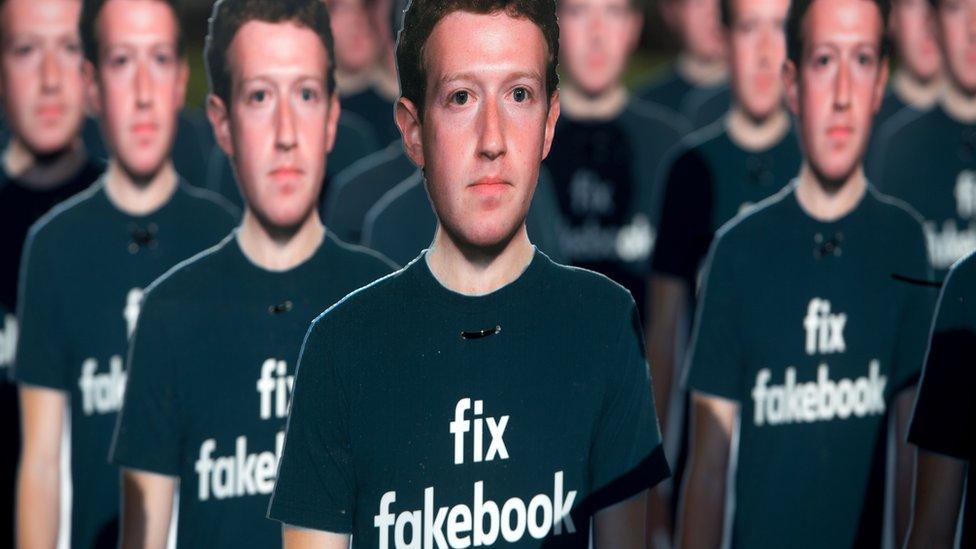

There are also digital awareness campaigns, additional funding for teams of experts in charge of detecting disinformation, and broader commitments that social media giants Google, Facebook, and Twitter have made. Those include making political advertising more transparent and removing fake accounts.

A "Rapid Alert System" has also been created to help European governments respond in real time to new disinformation threats. However, European Commission spokesperson Johannes Bahrke confirmed to the BBC no alert has yet been triggered.

Could other actors be engaging in disinformation?

In their search for signs of Russian disinformation campaigns, experts have spotted evidence of similar attempts to deceive - emerging not from Kremlin-linked outlets, but from partisan groups based inside the EU.

"These groups seem to be pushing highly polarised content," says BBC Monitoring's Olga Robinson. "Some of the messages I have seen over the past few weeks have been built on complete lies."

Populist groups in Italy have spread disinformation ahead of the European elections

She says many of these messages echo pro-Kremlin disinformation.

"It doesn't mean that they are in any way connected. It might be that Russia is tapping into this kind of Eurosceptic agenda and they have been doing that for a very long time," she says.

What does Russia say about these accusations?

In a statement, the Russian Embassy in London described accusations of election interference as "completely false" and "unsubstantiated".

Trending also approached Russian news channel RT for comment. In a statement, deputy editor-in-chief, Anna Belkina, said disinformation claims against Russian media outlets "serve to silence and force out legitimate voices from public debate."

"It is beyond naive to think that if RT didn't exist, the issues we cover wouldn't exist," she said. "Overlooking dissenting voices is what has long undermined the media-political establishment, not RT."

Could the EU be overplaying the seriousness of the threat?

Despite all the media attention that has been given to the subject in recent years, some academic research, external has actually called into question the reach of disinformation and fake news throughout the continent.

There are also those who, though acknowledging that Russian-backed disinformation is real, argue that the EU's response is misguided.

"By focusing on [Russian disinformation], the European Commission is shifting the focus from the more pressing underlying political issues and that's dangerous," says Julia Rone, a researcher at Cambridge's Department of Politics and International Studies.

"There are people who are legitimately worried about economic inequality, about youth unemployment, and especially about immigration," she says. "There's a lot of mobilisation from the far-right all across Europe and it cannot be attributed simply to foreign agents."

If you'd like to find out more about this story, listen to our podcast.

Story by Marco Silva, external.

You can follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.