How death threats spread in pro- and anti-Brexit Facebook groups

- Published

After angry scenes in Parliament, both pro- and anti-Brexit groups were flooded with threats

MPs have been criticised for the angry, aggressive tone of recent debates in the House of Commons.

But on Facebook, things are much worse.

A BBC investigation has found that several of the most popular and influential closed Facebook groups about Brexit - both for and against - are filled with violent language, including dozens of death threats aimed at individual MPs.

Facebook says it does not allow hate speech, and is investigating the material found by the BBC.

What did the posts say?

We gained access to some of the largest and most active closed or "private" pro- and anti-Brexit Facebook groups and examined them following the tumultuous scenes in the Commons.

The groups had thousands of members and, in some cases, tens of thousands.

Unlike in open or "public" groups, posts in closed "private" Facebook groups can only be seen by approved members.

A common theme in the pro-Brexit groups is wanting to hang opposition MPs for "treason". This cropped up repeatedly, in posts by multiple Facebook users, in multiple private groups.

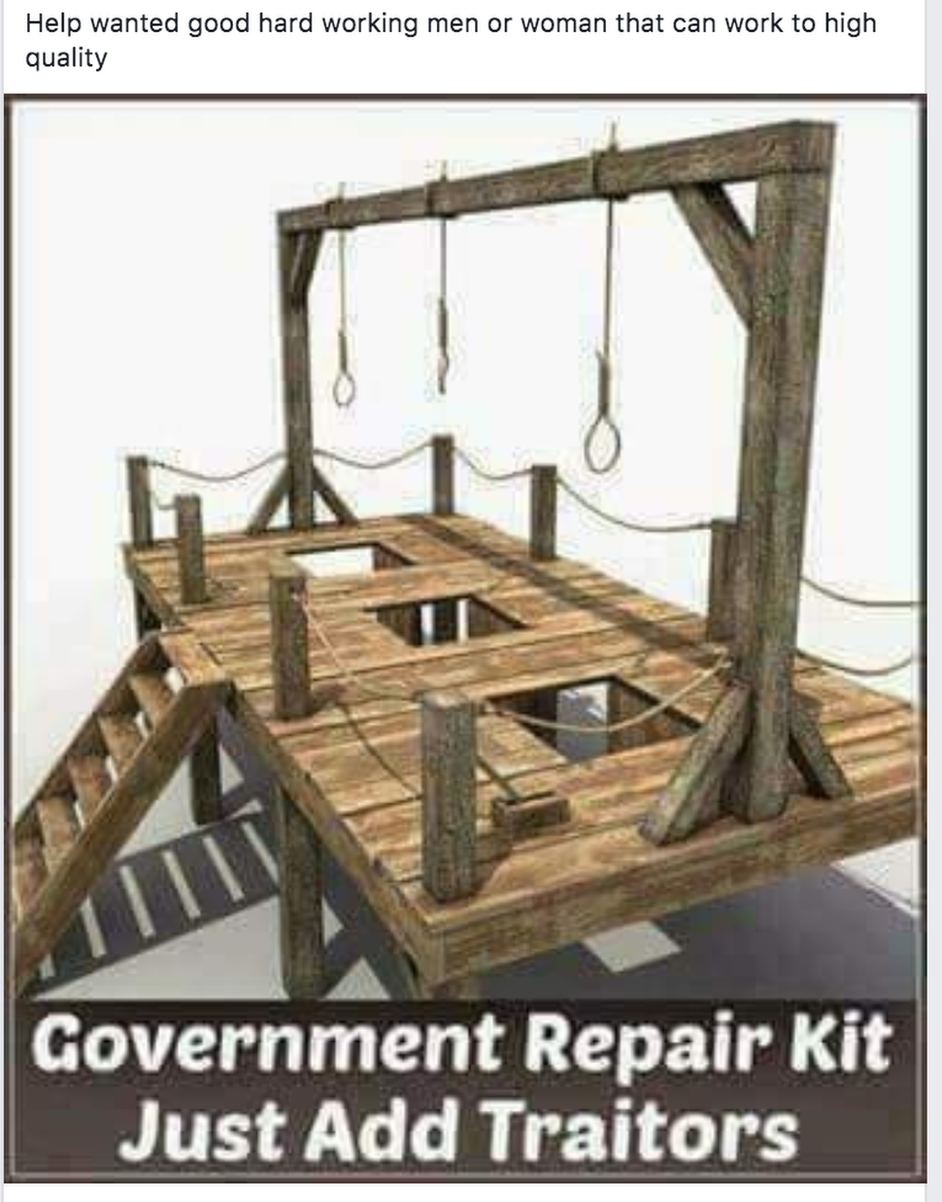

For example this post appeared in one pro-Brexit group:

Many posts spoke of hanging MPs for treason

Earlier this year, Labour MP Yvette Cooper questioned a Facebook representative about closed groups at a parliamentary hearing, highlighting one with 30,000 members which included a post calling for her and her family to be shot. The group was later removed.

Cooper told the BBC: "We have raised concerns about closed groups with Facebook on a number of occasions and their answers have never been good enough."

"Social media companies have a responsibility to proactively seek out this content both with technology and proper moderators," she said.

In August, Facebook changed the name, external of "closed" groups to "private" groups. Groups once referred to as "open" are now called "public" on the network.

In a statement, a Facebook spokesperson said: "Every single piece of content in private groups can be reported to us. We also use artificial intelligence technology to proactively identify and remove harmful content in these groups, as we do across Facebook.

"Where we see harmful content in private groups, we remove it.

"The proportion of content we remove proactively thanks to this technology and also reactively in response to user reports is broadly the same across public and private groups."

Yvette Cooper has previously expressed frustration with the tech firms

Cooper argues that independent regulation is needed, as well as bigger fines for companies that are slow to deal with violent content.

In response to the BBC investigation, she said: "Complacency or claiming ignorance is outrageous when we all know the appalling consequences there can be if hateful and violent content is allowed to proliferate."

Another image in a pro-Brexit Facebook group

Death threat comments

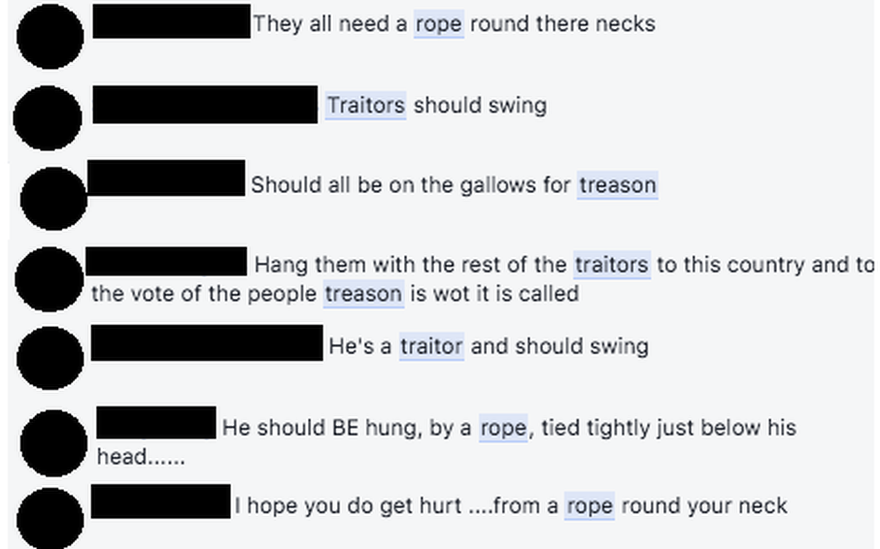

As well as pictures like the ones above, violent messages appear in the comments section beneath more innocuous posts.

The BBC found dozens of examples of such comments in closed groups, including multiple examples of death threats aimed at specific MPs.

The profiles of the commenters indicate they are real people who live in the UK.

Dozens of the comments contained death threats against MPs

Anti-Brexit groups

Of the multiple closed groups seen by the BBC, pro-Brexit ones tended to have more violent content.

A Newsnight investigation at the time of the European elections in May reached the same conclusion.

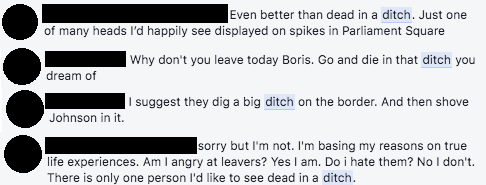

However, we found that Remain-backing groups also contained violent comments, including death threats.

Pro-EU groups also contained death threats

What's next for privacy on Facebook?

Facebook is in the process of increasing its focusing on private communication, following scandals such as the one involving Cambridge Analytica,

"I believe the future of communication will increasingly shift to private, encrypted services where people can be confident what they say to each other stays secure and their messages and content won't stick around forever," chief executive Mark Zuckerberg wrote in a blog post, external earlier this year.

"Privacy gives people the freedom to be themselves and connect more naturally, which is why we build social networks," he wrote.

In practice, this means a greater emphasis on closed spaces such as private groups or Facebook Messenger rather than on public groups or the public News Feed. However, experts say this means extreme content can spread virally, largely unnoticed by outsiders.

"Closed social media channels have become a hotbed of illegal and harmful content over recent years," says Chloe Colliver of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a think tank that investigates online extremism and polarisation.

"With little to no access for researchers in these spaces, social media platforms' responsibility to monitor and remove illegal and threatening behaviour is going largely unchecked, including in closed Facebook groups."

Last year's yellow vest protests in France were largely organised in closed Facebook groups, external, meaning authorities knew very little about them until they suddenly turned violent, external, while during recent election campaigns in India and Brazil, misinformation spread in groups on WhatsApp, the encrypted chat app owned by Facebook.

Closed groups have also been associated with medical conspiracy theories, external and sexist bullying, external.

Tech giants, such as Facebook and Google, are set to play a huge role in the next UK general election.

Chloe Colliver says the rise of closed groups "leaves public figures, but also vulnerable minority groups, open to increasingly violent attacks online, and the subsequent fear of violence spilling over into the offline world.

"The threat to our democratic representatives and the broader ability for all citizens to feel safe engaging in democratic debate is enormous."

A Facebook spokesperson said: "The group raised by Yvette Cooper has been removed because it violates our policies, and we are investigating the additional content flagged by the BBC.

"In two years we've almost tripled the proportion of hate speech we proactively remove from Facebook before it's reported to us to 65%, but we know there's more to do. We'll continue to improve our technology and engage with policymakers to ensure our platforms remain safe."

What did you think of this story? Have you seen something worth investigating? Email us, external

Follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, and find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.