Coronavirus: How bad information goes viral

- Published

There's a huge amount of misleading information circulating online about coronavirus - from dodgy health tips to speculation about government plans. This is the story of how one post went viral.

It's a list of tips and advice - some true, some benign, and some possibly harmful - which has been circulating on Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, and elsewhere.

Dubbed the "Uncle with master's degree" post because of the alleged source of the information, it's hopped from the Facebook profile of an 84-year-old British man to the Instagram account of a Ghanaian TV presenter, through Facebook groups for Indian Catholics to coronavirus-specific forums, WhatsApp groups, and Twitter accounts.

At first glance it seems legitimate because the information is attributed to a trusted source: a doctor, an institution, or that well-educated "uncle".

Poster Zero

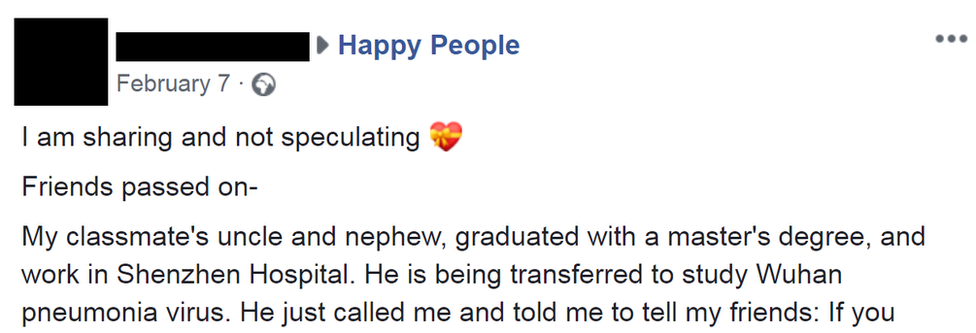

The earliest version that we could find was posted by a Facebook user on 7 February. It was shared in a group called Happy People, with nearly 2,000 members.

The post read: "My classmate's uncle and nephew, graduated with a master's degree, and work in Shenzhen Hospital. He is being transferred to study Wuhan pneumonia virus. He just called me and told me to tell my friends…"

The tips that follow are misleading or wrong. One says that you don't have the virus "if you have a runny nose".

According to fact checking organisations Full Fact, external and Snopes, external, citing health authorities including the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and The Lancet medical journal, a runny nose is uncommon - but it's not unheard of among coronavirus patients.

The post also encourages people to "drink more hot water" and "Try not to drink ice". There's currently no medical evidence that either of those things will help prevent or cure coronavirus.

"That has no support," says Alex Kasprak of Snopes. "It's wild to see that in there, it's a big red flag."

We attempted to contact the person who posted the information; she did not respond.

The post spreads

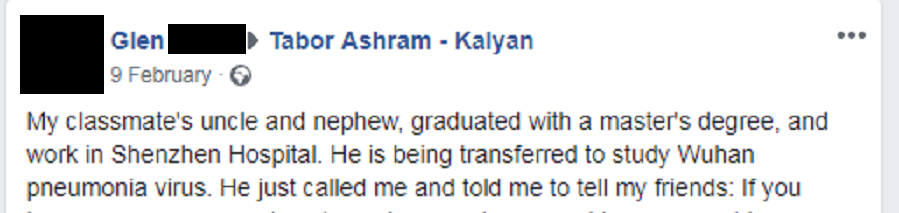

The list picked up momentum several days later when it was shared by a man named Glen in India. He put it in several different Facebook groups, including ones for Catholics.

The new post built on the 7 February post with additional information. Although the new post stated "My classmate's uncle and nephew, graduated with a master's degree ... just called me and told me to tell my friends...", Glen didn't actually receive a phone call from an uncle.

He says the post was just "a forward that I got and forwarded it on".

The additional tips included some accurate advice - for instance, it tells people to wash their hands, a key preventative measure.

But the new version also added some unsubstantiated and misleading information.

For instance, it described in very specific detail how the disease progresses. But doctors say coronavirus symptoms and severity are highly variable, and there's no one exact progression pattern.

The post goes viral

For several weeks the post was confined to relatively minor outlets. But on 27 February, an 84-year-old former art gallery owner named Peter made it really go viral.

Peter's post was similar to Glen's, but again included some new information - some of which was wrong or misleading.

Peter's post spread rapidly, bringing it to the attention of fact checkers including Full Fact and Snopes. Both organisations wrote detailed, external stories debunking the claims, external, citing reliable medical sources including the WHO, external, the US CDC, external, the UK National Health Service, external (NHS) and others.

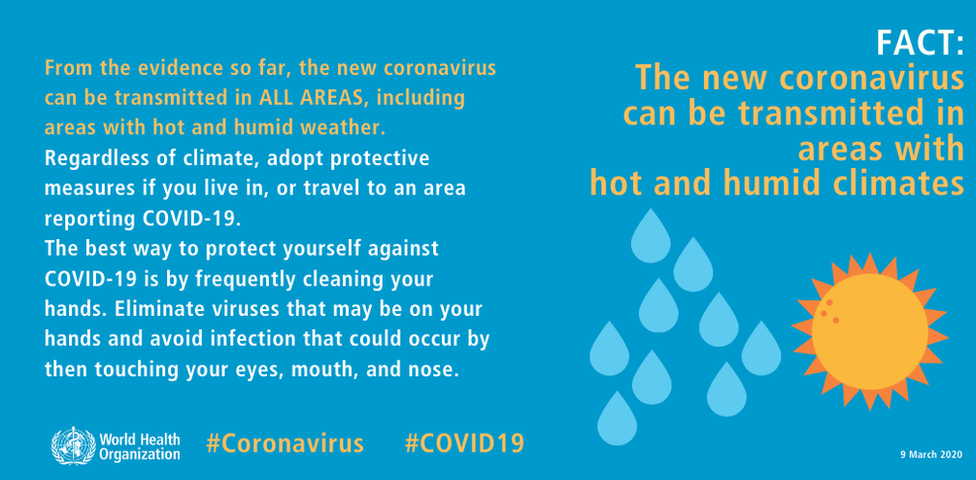

For instance, one claim in the post stated that the virus "hates the Sun". While there is evidence that ultraviolet rays and heat can kill viruses on surfaces, the post claimed that sunlight could cure or prevent the disease in humans. Simply put, going for a walk in the sunshine will not stop coronavirus.

Other claims in the post were factual. For instance, it repeated the advice about hand-washing.

Peter, who lives in southern England, edited the misleading parts of his post after the fact checkers posted their stories. But by then, it had already been shared nearly 350,000 times.

When contacted by the BBC, Peter would not say specifically where he got the information in the post, but said that he trusted his source at the time.

"I believed him actually to be a relation of this scientific guy, a medical guy who'd given all those facts and figures," he told us in a phone interview.

Peter says he was trying to help people protect themselves.

"I try to be as factual as I can. And if I'm corrected, or if I discover myself that I've said something incorrectly, I apologise and I amend it," he says.

The post mutates

Despite his fact-based edits, the claims in the original version of Peter's post soon spread, and mutated. Some versions started to absorb further misleading information.

The source shifted as well. In some versions, which moved beyond Facebook to Whatsapp and Twitter, the "uncle with a master's" became "a member of the Stanford hospital board" and even "a friend's sister's friend's brother who just happens to be on the Stanford Hospital board". There was also information attributed to "Japanese doctors" and "Taiwanese experts" - among many other modifications.

The posts mentioning Stanford - at least 100 have appeared on Facebook alone - spread so rapidly that the university issued a statement denying it had anything to do with them.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The post crosses languages

The post then spread - helped by celebrities, including a Ghanaian TV presenter and an American actor, but also by scores of ordinary people.

One American woman posted a version in a Facebook group called Coronavirus Updates - one of thousands of virus-focused groups that have blossomed on the social network.

April's post was attributed to "a friend's nephew in the military".

She explained when contacted via Facebook Messenger that she had seen the information when a friend shared it, but later realised that "all [my friend] did was copy and paste it like I did. Looks like most of it is false."

"I use Facebook all day long, everyday," April says. "I have found lots of helpful information... I don't watch the news."

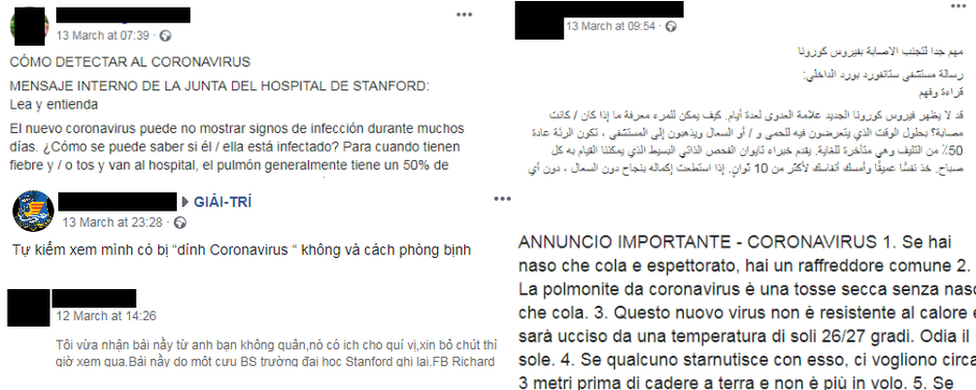

At the same time the post was translated into several languages including Arabic, Amharic, Vietnamese, French, Spanish and Italian.

Just a few of the many versions of the post that appeared in different languages

Again, some of the posts contained accurate or at the worst benignly misleading information - but other alleged "facts" had the potential to be harmful.

One piece of advice suggests doing a coronavirus "self-check" every morning by holding your breath for more than 10 seconds. But there's no evidence, external to indicate that your ability to do this means you are virus-free.

Beyond "fake news"

Copypasta

"Uncle with a master's" is a specific type of viral post - the slang term for it is "copypasta, external". This is material that someone copies and pastes instead of using "share", "retweet", other sharing tools provided within social networks.

That makes each post look original: it looks like it was written by someone you know, possibly a friend or relative, thus increasing the chance that you might trust it.

Because there are so many "original" posts, it also makes it difficult for social networks and people who study them to keep track of exactly how far such posts have spread.

We know that Peter's single post was shared hundreds of thousands of times - but it's a colossal, perhaps impossible, task to calculate how many people have seen the various copied variations of "uncle with a master's" on Facebook, or any of the major social networks. Clearly though, millions have.

A fact-checker's guide to stopping fake news

What Facebook is doing

Of the misleading posts that weren't edited to remove misinformation, a Facebook spokesperson told us: "These posts violate our policies and have been removed."

"We are working continuously to remove harmful misinformation about coronavirus," the spokesperson said. "Facebook has also partnered with the NHS to connect people to the latest official NHS guidance around coronavirus - both directly in their News Feeds and when people search on the topic."

The company is also plugging the text from the posts into automated systems in order to detect similar content. The tech giants - Facebook, Microsoft, Google, Linkedin, Reddit, Twitter and YouTube - have pledged to work together to fight virus misinformation, external.

Fact checkers say that we all have a part to play - by thinking before we share.

"Pause for a second. Have a little look. See if you can find out more information about it," says Claire Milne from Full Fact. "Work out if it's correct or if you are sharing something with your friends and family that might be misleading and could harm them."

If the source seems vague or the post is a long list or thread packed with information, compare the claims to known, trusted sources.

Blend of truth and nonsense

The people sharing the "uncle with a masters" post - which in its various versions is still spreading online - generally aren't being malicious: they usually believe that they're passing on facts. Or they may be unsure about the veracity of the information, but believe that they're helping anyway, "just in case" what's outlined is true.

In general, they aren't foolish or stupid. It's easy to get duped if you're anxious.

The "uncle" post is also a blend of truth and nonsense, which makes it more pernicious and easily spread.

"When things [that are false] are mixed with things that sound reasonable or true, it confuses people, and in some cases, it allows people to think that the rest of the advice is legitimate as well," says Mr Kasprak from Snopes.

Three questions to ask before you share

Does the source of the information seem vague or seem to be from a friend of a friend you can't trace? Get to the bottom of where the story came from - or don't share it. Just because you were sent it by somebody you trust, doesn't mean they received the information from someone they actually know.

Does all of the information seem true? When there are long lists, it's easy to believe everything in them just because one kernel of advice is correct - that might be the case.

Does the content make you emotional - happy, angry or scared? Misinformation goes viral because it plays on our emotions, so that's a sign that it might not be true. Again, dig a bit deeper. Scientific breakthroughs, prevention advice or public announcements will come from reputable sources.

Sources: Full Fact, Snopes, BBC Monitoring

Have you seen misleading information? Is there a story we should be investigating? Email us, external

Subscribe to the BBC Trending podcast. Follow BBC Trending on Twitter @BBCtrending, external, or find us on Facebook, external. All our stories are at bbc.com/trending.