Coronavirus: Inside the pro-China network targeting the US, Hong Kong and an exiled tycoon

- Published

Hundreds of fake or hijacked social media accounts have been pushing pro-Chinese government messages about the coronavirus pandemic on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, a BBC investigation has found.

The network of more than 1,200 accounts has been amplifying negative messages about those critical of China's handling of the outbreak, while praising Beijing's response.

Although there is no definitive evidence that this network is linked to the Chinese government, it does display features similar to a state-backed information operation originating in China that Facebook and Twitter removed last year.

The accounts uncovered by the BBC also share similarities with a resurgent pro-Chinese network spotted by the social media analytics firm Graphika, external earlier this year. Dubbed "Spamouflage Dragon", that network both pumped out political messages and targeted Chinese authorities' critics with spam.

China and the US have been involved in a war of words over the origin of Covid-19 and their response to it. Government officials, senior politicians and media outlets in both countries have used traditional and social media to exchange accusations and unverified claims.

Having increased its activity over the past few months, the network uncovered by the BBC continues to grow and add new accounts. But despite posting content prolifically, it has relatively low impact. Many of the accounts failed to gain a significant following.

After BBC News reported its findings to all three social networks, the majority of the accounts, pages and channels were removed.

What messages are being spread?

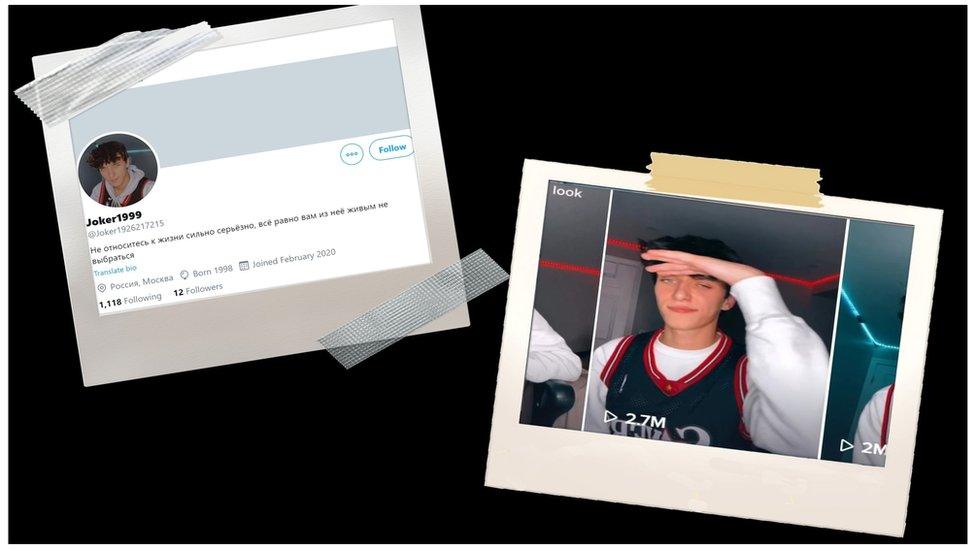

At first look, "Joker1999" might look like any other account on Twitter - it has a profile photo, a short biography and it retweets messages about politics.

But upon closer inspection, it's clear the account is fake. Its profile image has been taken from a TikTok celebrity and, while it claims to be a blogger from Russia, the account tweets about politics mainly in Chinese.

The profile photo of Twitter user "Joker1999" is taken from videos by TikTok influencer Josh Richards

"Joker 1999" is one of hundreds of fake accounts amplifying Chinese government messages across Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. The majority were created between January and May this year.

The accounts criticise the US handling of the coronavirus outbreak, post negative messages about the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement and specifically target Guo Wengui, an exiled Chinese property tycoon in the US who has been an outspoken critic of the Chinese government, including for its handling of Covid-19.

Some accounts focus on only one topic while others post on a range of themes or go dormant and then switch topics.

Exiled tycoon and critic of the Chinese government Guo Wengui was one of the targets of the network

Chinese authorities have previously accused Mr Guo of financial crimes and rape, which he denies. He has business ties to Steve Bannon, external - President Donald Trump's former chief strategist - and he's behind a website that published unproven claims about the origin of the virus, external.

Cross-platform operation

The BBC identified more than 1,000 Twitter accounts, 53 Facebook pages - with just under 100,000 combined followers - 61 Facebook accounts, and 187 YouTube channels with a total of around 10,000 subscribers. While not insignificant, the follower counts were nowhere near levels that would be considered highly influential.

According to data from the Facebook-owned social media analytics tool CrowdTangle, those 53 pages had not managed to attract more than a few thousand interactions between early April and early May.

On Twitter the network of automated accounts - otherwise known as "bots" - largely focused on criticising Mr Guo. They would retweet, like and comment on posts to attempt to make them trend, using tags such as #GuoWengui and his name in Chinese.

Similar to "Joker1999", the accounts often used stolen or hijacked profiles of Russian speakers and featured fake profile pictures. Many of them were also created on the same day, a further clue indicating they are part of an automated network.

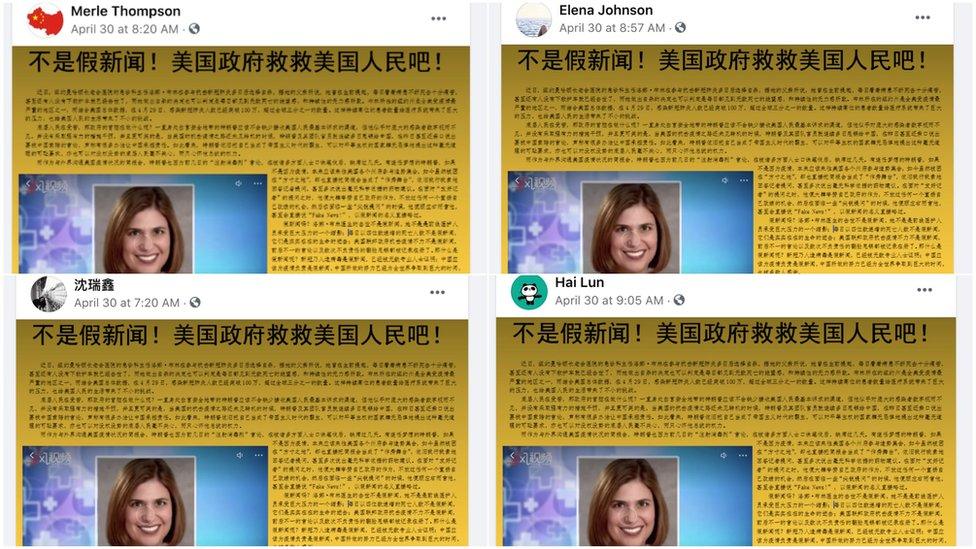

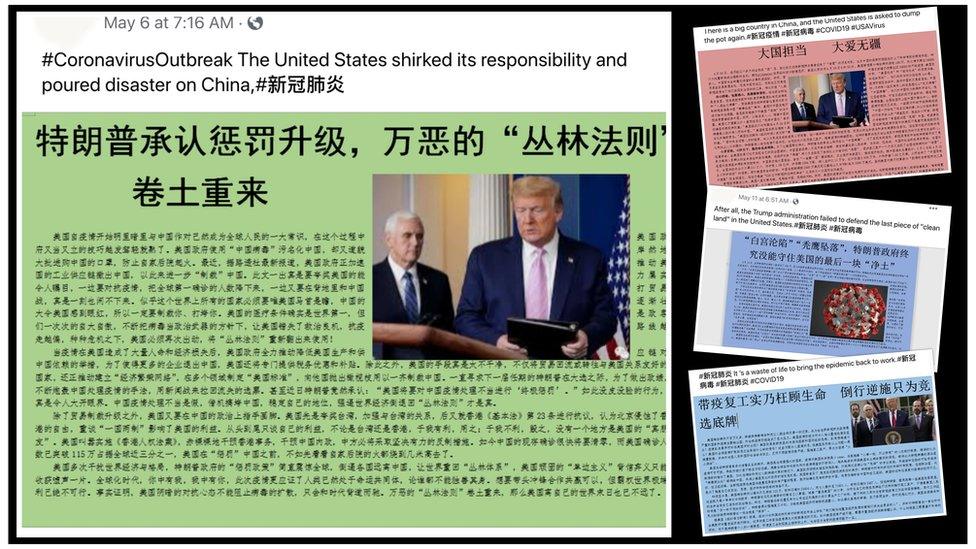

Several Facebook accounts shared the same meme about the US government's handling of the epidemic on the same day

On Facebook, the network focused strongly on the coronavirus pandemic and in particular on spreading criticism of the US handling of the outbreak, although some accounts also promoted negative messages about Mr Guo and the Hong Kong independence movement.

Although the network largely sprung up in early 2020, a few accounts also had a longer history, and posted criticism of anti-Chinese government protests in Hong Kong last summer.

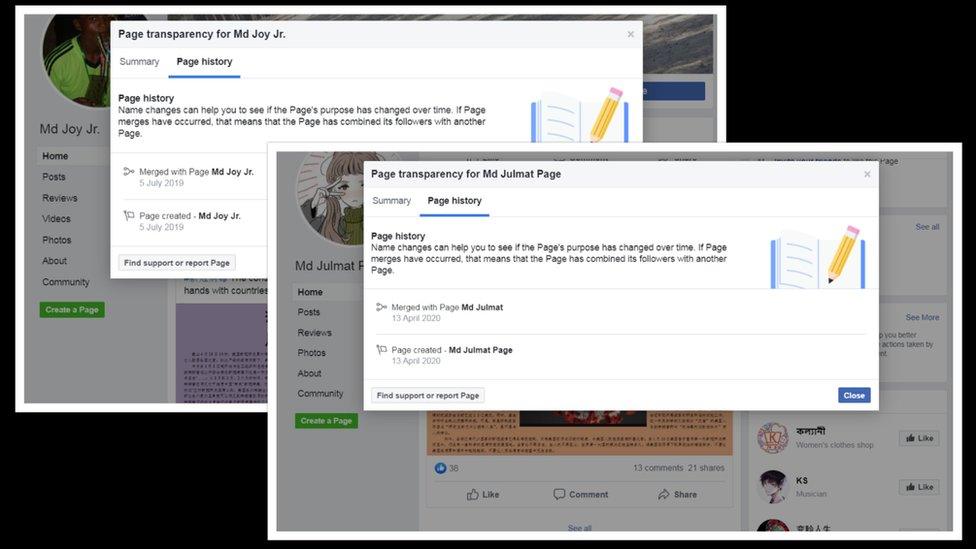

The BBC found evidence that at least some of the Facebook pages and accounts originally belonged to users from Bangladesh before they were either hijacked or sold and repurposed to post in Chinese. These accounts had multiple personal pictures on their timelines, listed users predominantly from Bangladesh among their Facebook friends and sometimes even exchanged comments in Bengali on their timelines, before abruptly changing their language and identity overnight.

A few accounts also used Russian or English names, although at times they confused genders, for instance using a male name alongside a female profile picture.

A common tactic used by Facebook pages on the day they were created was to immediately merge with another page

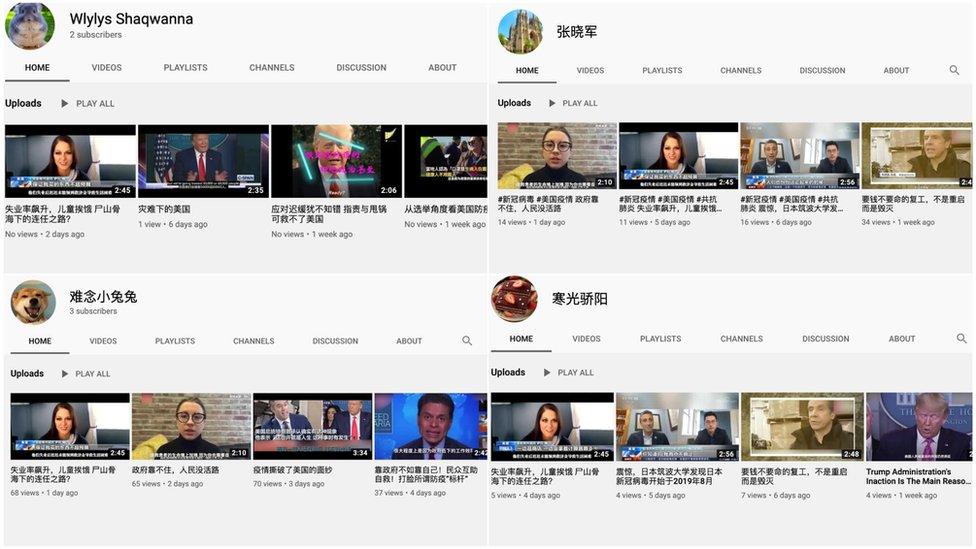

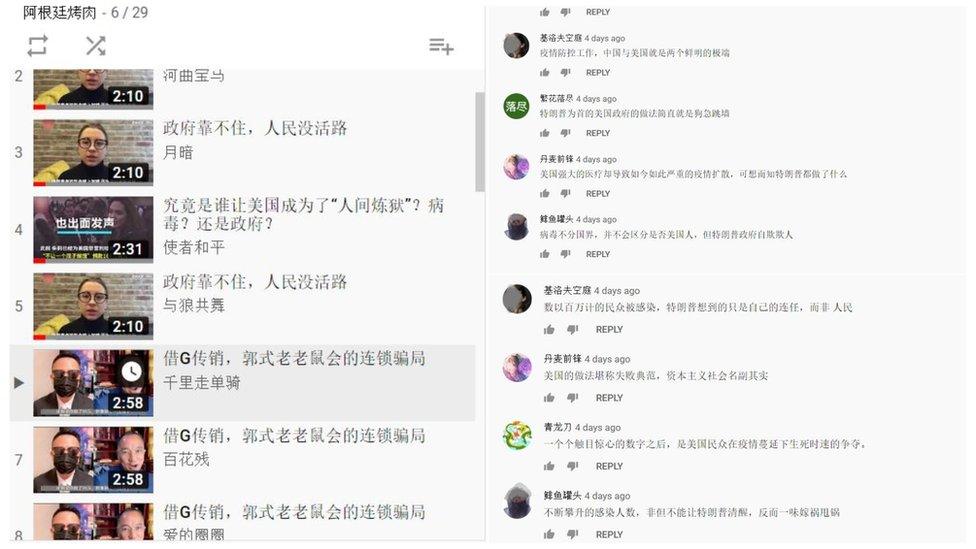

On YouTube, the network focused on videos about coronavirus fatalities in the US, and Mr Guo. Channels uploaded the exact same videos over a short period of time, liked and commented on each other's videos, and created playlists of their content.

The network had a core of uploaders with dozens of videos, while some channels only uploaded one or two and mostly focused on boosting the videos of channels with more subscribers.

'Art imitating reality'

The operation was closely coordinated, with dozens of accounts posting the same memes and videos in Chinese and English multiple times, often within minutes of each other.

Some of the pages and accounts mixed highly political messages with softer content: animal videos, clips of video games, shots of Asian models, and pictures of nature and food. This mix was most likely an attempt to build large followings while hiding the coordinated and political nature of the main content.

The network regularly blamed President Trump's administration for its coronavirus response

Even before most of its accounts were taken down, the network struggled to gain much traction outside of its bubble. Most engagements - shares, likes, retweets, comments, views and mentions - come from inside the network, rather than from genuine users.

"In this case, it looks like the network is trying to generate a high volume of pro-Chinese government content, and then to hide it by surrounding it with spammy content," says Ben Nimmo, the director of investigations at Graphika.

The intention is to attract the attention of genuine users to the messaging, Mr Nimmo says, "but it's being done in an unsophisticated and relatively amateurish way".

Many of the YouTube channels uploaded the same videos about the US government's response to Covid-19

He says the purpose of networks like this is to create the impression that a lot of social media users support a particular narrative or group; in this case, the Chinese government.

"The problem is that this sort of large-scale frontal assault is too crude to convince many people. It is art imitating reality, but badly."

'Persistent threat actors'

The set of accounts uncovered by the BBC appears to be a larger part of the "Spamouflage Dragon" network exposed by Graphika, external, Mr Nimmo said.

"If it is the same network, it went through a batch of takedowns in autumn 2019, and there was another batch of takedowns this spring," he told BBC News.

Threats of punishment to Hong Kong's pro-democracy protesters were common in the network's memes and videos in both English and Mandarin

The network scaled down its activity late last year and mostly posted spam content in November, December and January.

"It kicked into higher gear once the coronavirus outbreak became a major public relations problem for China," Mr Nimmo said.

Despite the repeated takedowns, the network continued to create, buy or rent fake or hijacked accounts and repurpose them to post Chinese content, albeit at a lower rate than earlier in the year.

"This is a pattern we see with the more persistent threat actors: they keep trying to come back, but the repetitive effect of being exposed and taken down squeezes the space they have to operate in, and forces them to try to hide instead of trying to build an audience," Mr Nimmo said.

The network's YouTube assets commented on and created playlists of each other's videos

A Twitter spokesperson told BBC News: "Platform manipulation is a violation of our policies and we will take strong enforcement action on any account engaging in these behaviours, regardless of the content they Tweet. If and when we can reliably attribute these permanently suspended accounts to a coordinated state-backed operation, we disclose all content to our public archive - the only such example in the industry."

A Facebook spokesperson said: "We are grateful to the BBC for reporting these accounts and pages, the majority of which we had already removed under our inauthentic behaviour policies. We are investigating the remaining accounts."

A spokesperson for YouTube said: "As part of our ongoing efforts to combat coordinated influence operations, over the past several weeks we removed more than a thousand channels that violated our spam policies. Channels in these clusters behaved in a coordinated manner while primarily uploading spammy non-political content, although a small subset posted primarily Chinese-language political content, similar to those described in a recent Graphika report."

Additional reporting by Wanyuan Song and Flora Carmichael

Graphics by Simon Martin

Is there a story we should be investigating? Email us, external

Follow us on Twitter @BBCtrending, external or on Facebook, external.

- Published4 May 2020

- Published26 April 2020

- Published20 August 2019

- Published20 April 2020

- Published19 March 2020