Philippines election: 'Politicians hire me to spread fake stories'

- Published

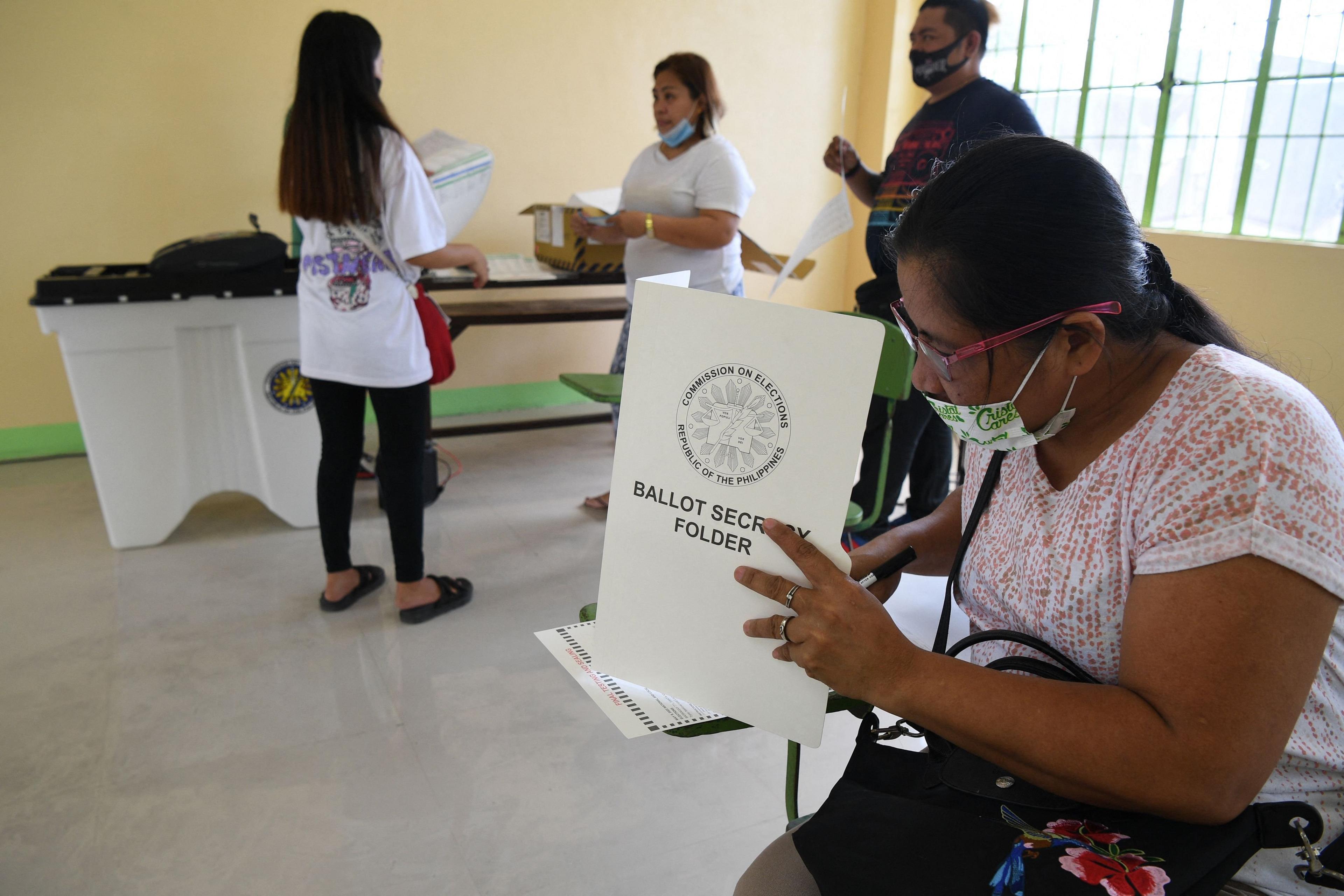

On Monday, voters in the Philippines will pick the nation's next president - amid a tide of falsehoods and social media lies.

"I consider myself a troll - or, politically speaking, I'm a social media marketing consultant."

Jon - not his real name - is part of an industry that could be crucial to the selection of the next president of the Philippines.

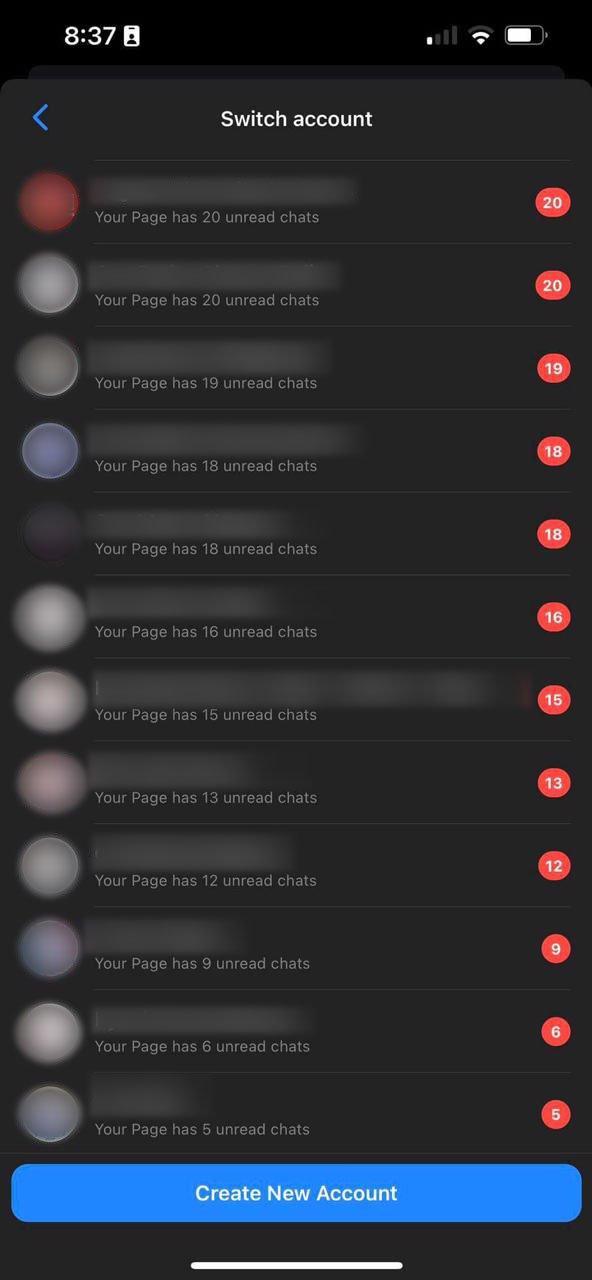

He says he's been working most days from 10:00 to 03:00, managing hundreds of Facebook pages and fake profiles for the benefit of his clients - politicians and their campaigns.

He says his customers include governors, congressmen and mayors.

'Jon' uses fake IDs to set up multiple accounts on Facebook

On Monday, Filipino voters will go to the polls to select their next president, along with candidates for several lower offices. It's the first presidential election since Rodrigo Duterte's triumph in 2016 - one which critics say was achieved on the back of a wave of false news.

According to election observers and disinformation experts, the situation hasn't improved since - in fact, it may have even got worse.

Disinformation systems

Jon is part of this disinformation ecosystem. He says he has around 30 "trolls" working directly for him. Their aim is to boost support for their clients, even if it means spreading falsehoods. He says he's been operating under the radar for years. Sometimes they're searching for what he calls "skeletons in the closet" - fairly typical opposition research. But at other times, they make things up.

"In 2013, we spread fake news in one of the provinces I was handling," he says, describing how he set up his client's opponent. "We got the top politician's cell phone number and photo-shopped it, then sent out a text message pretending to be him, saying he was looking for a mistress. Eventually, my client won."

Jon runs multiple pages and accounts aimed at boosting the profiles of his political clients

To prove the authenticity of his claims, the BBC was sent videos of different accounts which Jon runs on Facebook, as well as screenshots of WhatsApp messages between him and people he works for, bank slips, and fake IDs and SIM cards used to circumvent Facebook verification processes.

Due to concerns expressed about his safety, we are keeping his identity anonymous.

Another trick he uses, he says, is the creation of non-political pages and groups that eventually push out political propaganda.

Meta - which owns Facebook- says that in the Philippines, it has removed a number of networks which have attempted to manipulate people, including a cluster of more than 400 accounts, pages, and groups that violated their policies.

'Open secret'

In the lead-up to the country's vote, many candidates have aired concerns about the role that disinformation could play in the outcome.

In an interview with a Filipino news channel, presidential candidate Leni Robredo said her initial approach to the problem of fake news - to ignore it - "did not work".

She added: "Lies repeated again and again become the truth."

Fact-checkers claim Presidential candidate Leni Robredo is the biggest victim of disinformation

Another presidential candidate, former boxer Manny Pacquiao, has spoken about the need to "control" fake news and disinformation.

"What we've seen is a cat-and-mouse game between platforms, fact-checkers and academics trying to expose these kinds of disinformation operators, and [the operators] finding ways to evade detection," says Jonathan Corpus Ong, an associate professor and disinformation researcher at Harvard University.

In 2018, Ong co-authored a report based on a year of anonymous interviews with strategists and digital workers behind false news stories in the Philippines.

He argues that there's a hierarchy of people involved in disinformation - starting with advertising and PR strategists who call the shots and assemble influencers and fake account operators.

Ong claims that it's an "open secret" who these people are, even as payments to them are made "off the books".

Co-ordinated behaviour

The Philippines is also home to a collection of groups seeking to counter disinformation - including lawyers, church leaders, universities and media firms.

The BBC spoke to experts including Celine Samson, head fact-checker at Vera Files, part of the fact-checking coalition tsek.ph, and Tony La Vida, a lawyer who leads the Movement Against Disinformation coalition.

Both identified possible signs of co-ordinated behaviour - including repeated posts from multiple pages, or across platforms, being uploaded within a tight time-frame.

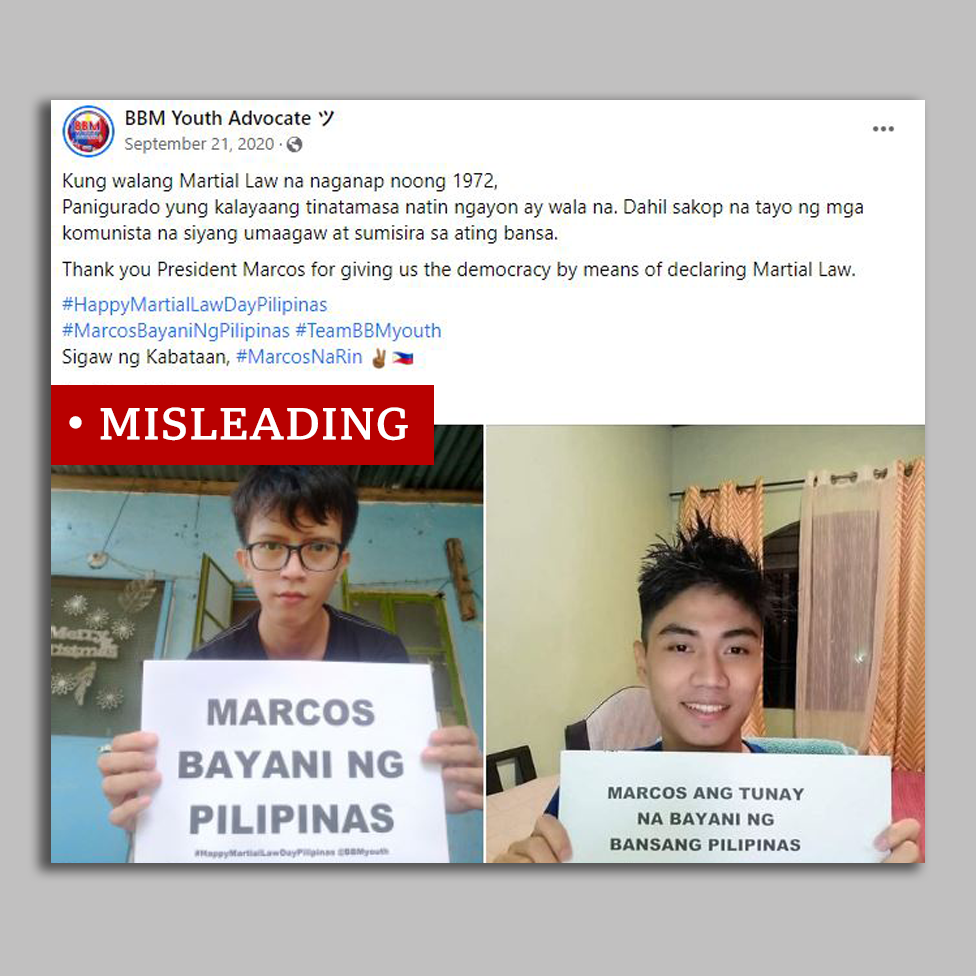

Earlier this year, tsek.ph published a study suggesting that presidential candidate and polling front-runner Ferdinand "Bong Bong" Marcos Junior is the biggest beneficiary of fake news, while his political rival, Leni Robredo, is its biggest victim.

Claims that the introduction of martial law stopped the country being overrun by communists have been spreading for years, and have been debunked by fact-checkers

The rule of Mr Marcos senior, which lasted more than two decades until 1986, was characterised by widespread extrajudicial killings and the torture of opponents. According to Amnesty International, 70,000 people were jailed, 34,000 were tortured and 3,240 were killed.

Ms Samson says: "We looked at all the election-related disinformation we fact-checked in 2021, and found that a lot really propped up Bong Bong Marcos, trying to paint his family as one that didn't steal wealth from the government coffers, and painting his father as someone who didn't commit human rights abuses."

She added: "We also saw a lot of attacks on Robredo, painting her as incompetent or someone who makes nonsensical statements."

'Family rebranding'

Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Brittany Kaiser said in an interview with Philippine news outlet Rappler in 2020, that the company was approached by Marcos Jr in 2016, to do a "family rebranding".

A spokesperson for Bong Bong Marcos denied those claims at the time, labelling them "patently fake, false and misleading."

Earlier in the year, Twitter announced that they had suspended hundreds of accounts promoting Bong Bong Marcos for violating their rules on spam.

Presidential candidate Bong Bong Marcos denies using trolls to boost his campaign

We approached the Marcos Jr campaign for comment, but did not receive a response prior to publication. In interviews, Bong Bong Marcos has said he is a "victim" of fact-checkers who he said have their own "political agenda". He has denied the use of troll accounts to boost his campaign.

Are platforms doing enough?

According to the self-confessed troll Jon, he was approached by a friend who asked him to produce disinformation for a candidate running in the 2022 presidential elections - an offer he says he declined. The BBC is unable to independently verify this claim.

Jon did not disclose who the presidential candidate was, but said it was not Bong Bong Marcos.

Alongside Twitter and Facebook suspending and removing multiple accounts and pages, Google-owned YouTube says that between February 2021 and January 2022, it removed more than 400,000 videos uploaded from the Philippines.

Voters in the Philippines will be heading to the polls on 9 May

But questions remain over whether all of these efforts are enough.

"The time it takes to create fake news outpaces the time it takes to verify and debunk it," says Ms Samson.

With reporting by Micaela Papa