Brazil: The code word used to invite protesters to a riot

- Published

Protesters invaded palaces of the Presidency, the Supreme Court and the Congress in Brazil's capital

On Sunday, the world watched, stunned, as thousands of supporters of Jair Bolsonaro stormed Brazil's Congress, Supreme Court and presidential palace.

In echoes of the attacks on the United States Capitol almost exactly two years ago, they tore through buildings shouting the false accusation that the presidential election had been rigged, and that Bolsonaro was the true winner.

But how was a violent protest organised in plain sight of security services and social media moderators? The BBC's Global Disinformation Team has been investigating.

Invitations to a 'party'

In recent months, Bolsonaro's supporters have been spreading conspiracy theories online, pushing the idea that the former president was the real winner of the election. The BBC has found no evidence for these claims.

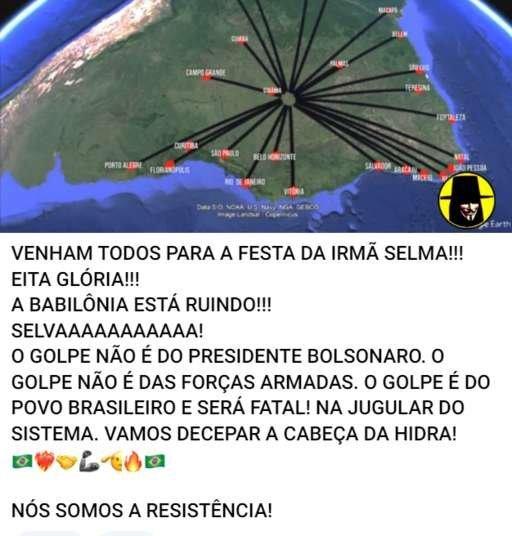

Message shared on Telegram in Portuguese says "Everyone come to the party of sister Selma"

In the days leading up to the attack on Brazil's Congress, the rhetoric intensified and included a series of thinly veiled metaphors. The main one was an invitation for Brazilians to attend 'Selma's Party'.

'Selma' is a play on the word 'selva', which means jungle in Portuguese, and is also used by the Brazilian military as a greeting or war cry.

Four days before the riot, a video about 'Selma's Party' went viral in groups on the social media app Telegram. In it, a man describes the 'ingredients' for the 'party', including a brand of Brazilian sugar called Union, and five large heads of corn. Corn is another wordplay. 'Milho' means corn and 'milhão' means a million. The suggestion is that five million people were invited to attend the protest.

Other posts on social media offered free transportation from different parts of the country to Brasília. They advertised "free buses" with "everything for free: water, coffee, lunch, dinner".

The party metaphor continued on the day of the protests on Twitter, where a video was posted showing hundreds of people marching with a long yellow and green banner in Brasilia. The caption reads: "The first guests are arriving… As soon as everyone gets here, the cake can be cut."

Security forces operate as supporters of Brazil's former President Jair Bolsonaro demonstrate outside the Congress Palace in Brasilia

Evading moderators

Most social media platforms prohibit and take down calls to violence. It's likely metaphors like 'Selma's Party' were used to evade content moderators. In a TikTok video that has since been taken down, a woman explicitly says that she's no longer talking about politics on TikTok because she doesn't want her account to be removed. She then proceeds to talk about 'Selma's Party'.

Elsewhere, people have been posting about other 'parties', including one for Selma's cousin 'Telma', in São Paolo, and her sister 'Velma', in Rio de Janeiro. For now, these events have not gained much traction.

According to analysis by Arcelino Neto from the University of São Paolo, the words Festa Da Selma first appeared on Twitter on 5 January. They have since been used by more than 10,000 accounts in tweets that were shared more than 53,000 times.

The hashtag #festadaselma was used to 'invite' people to turn up at a the complex of government buildings known as "Praça dos Três Poderes" (Three Powers Square) outside Congress.

On Telegram, the rhetoric was more explicit. Bolsonaro fans asked "hackers and IT experts" to "invade all government systems" and armed men to "protect the patriots".

They also invited reservists from the "military and police" to "share tactic experience and lead the seizure of Brasilia and its phoney government".

Brazilian authorities are under scrutiny for an alleged lack of plans to avoid the crisis.

"The coup is not by president Bolsonaro. The coup is not by the Armed Forces", reads another message shared days before the invasion. "The coup is by the Brazilian people and will be fatal".

Emillie de Keulenaar, a researcher from the University of Groningen who monitors pro-Bolsonaro groups on Telegram, has been looking into the language used.

She says that, after Lula's inauguration on 1 January, small private Telegram groups began to appear, organising events around different regions of Brazil.

On 6 January, she says the language used became "increasingly aggressive", inciting "civil war".

That's when metaphors began to appear. She says Bolsonaro's fans wanted to evade "infiltration by leftists who they think will confuse their plans".

"They used 'Festa da Selma' as a codename for the assault, but they also call it 'popular intervention', 'people taking power', or 'general strike'."

Lack of moderators

Protesters invaded palaces of the Presidency, the Supreme Court and the Congress in Brazil's capital

Social media's role in the riots is under scrutiny.

Since Elon Musk took over, Twitter has laid off staff including those in Brazil whose role was to tackle misinformation around the election. Twitter and Musk have repeatedly said they are addressing the most harmful content on the site.

It's not the first time that misinformation online has fuelled a physical assault on democracy. The former Chief Executive of Twitter, Jack Dorsey, admitted to a hearing into the storming of the U.S. Capitol in 2021, that misinformation on social sites played a role in inciting the violence.

Meta, which owns Facebook, and Google, YouTube's parent company have said they are removing content that praises or supports anti-democratic demonstrators in Brazil.

Edited by Rebecca Skippage