Are Africa's commodities an economic blessing?

- Published

Angola is one of a number of African oil producers

In terms of natural resources, Africa is the most abundant continent on earth.

But rather than a blessing, most of Africa's commodities have proved a burden; allegedly stoking conflict, funding wars and leading to rampant labour market abuse.

So, what is the history of Africa's biggest commodity crops? And what steps are being taken to improve the management of Africa's most valuable exports in the future?

Oil was first drilled commercially in Africa in Oloibiri in the Niger Delta, in 1956 by the Anglo-Dutch oil giant Shell.

There are now ten oil exporting nations in Africa, with another three soon to join that list.

BP has stated that Africa holds 127 billion barrels of untapped oil, almost ten per cent of global reserves.

Africa's largest single oil exporting nation is Nigeria.

While no official figures exist, Standard Bank estimates the country has made $6 trillion in oil revenue over the last 50 years.

The International Energy Agency says Nigeria holds 37 billion barrels of reserve oil, dwarfing that of Norway which has just 6 billion.

Yet 70% of Nigerians live under the poverty line and the country has consistently been ranked among the most corrupt on earth by international observers.

'Bunkering'

Oil related conflict in the Niger Delta remains a threat.

The pressure group Human Rights Watch claims more than 500 oil workers and civilians have been kidnapped in the region.

Hundreds more have been killed in violence between rival groups, fighting for a greater share of oil revenue and protesting over environmental damage caused by oil extraction.

Theft from standpipes, known as "bunkering", is estimated to cost Nigeria $5bn a year.

The current president Goodluck Jonathan has attempted to quell conflict in the Delta, offering militants cash payments, jobs and college places in return for laying down weapons.

He's also committed to a clean up of the Ogoni region of the Niger Delta, which has suffered serious environmental degradation.

Writing on his Facebook page, Mr Jonathan has warned Nigerians that oil reserves will not last forever, saying "when these resources dry up and/or the world finds an adequate alternative, we will have to rely on our environment for survival".

Despite its oil wealth, Nigeria has to import 60% of its own fuel because of a lack of domestic refining capacity and power blackouts are common.

Contracts cancelled

In 2007, oil was discovered in the Gulf of Guinea, off the coast of Ghana.

The huge "Jubilee" field is set to come on stream in the second half of 2010.

The International Monetary Fund says Ghana could make $20bn from oil by 2030, potentially transforming its economy and that of the tiny adjacent Atlantic islands of Sao Tome and Principe.

In March 2010, the Ghanaian government blocked a $4bn bid by the international oil giant Exxon Mobil to buy a 23% stake in the field.

The Norwegian oil firm, Aker, which won rights to develop the Jubilee field under the previous administration, has also been told its licence is now invalid.

Instead the government is lobbying to have the contracts awarded to the state-run Ghana National Petroleum Corporation.

President John Atta Mills plans to ring fence the proceeds of the oil trade in what's described as a "stabilisation" fund for the country's future.

He insists the government will account for "every pesewa" of oil money it receives.

'Blood diamonds'

There are 10 major diamond-producing nations in Africa, where the industry is worth $158bn a year - the largest being Botswana, where it generates a third of GDP.

The portability and high value of diamonds have made them a favourite source of funding for rebel groups across the continent.

Angola, Congo and the Cote D'Ivoire have all been subject to the trade in so called "blood diamonds", although the most high profile case has been in the West African state of Sierra Leone.

During the country's brutal 10 year civil war in Sierra Leone, the diamond mines in Kono were controlled by the rebel RUF forces, led by Foday Sankoh.

Diamonds smuggled from the region were allegedly passed on to Charles Taylor, president of neighbouring Liberia, who in turn helped arm the rebel movement.

In 2002 after the end of the war in Sierra Leone, and under pressure from campaign groups, the World Diamond Council devised the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme.

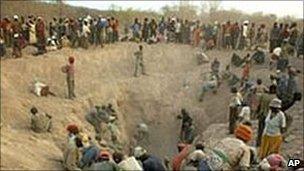

It is alleged human rights abuses are connected with some diamond production

It aims to stop gems mined in conflict zones being sold around the world to unsuspecting buyers.

The 45 participating members account for over 99% of global diamond production.

However campaign groups, such as Global Witness, say the scheme still falls short of what's required.

It claims diamonds from blacklisted countries like Zimbabwe are still routinely being traded on the international market, particularly in less well regulated jurisdictions such as Dubai, India and Mauritius.

Diamond production remains a major source of revenue for Africa.

In Sierra Leone, income from the diamond trade rose by a quarter to $35m in the first six months of the 2010.

Mobile phones

Coltan or "colombo-tantalite ore" is a mineral used to make electric capacitors in computers, gaming consoles and mobile phones.

One of the world's largest reserves is in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where more than 5 million people were killed in a decade long civil war, which ended in 2003.

International observers claim that the east of the country, the main coltan mining area, remains at risk of further conflict.

Most of the coltan mines in the DRC are in the remote South Kivu district.

In 2001 a report by the United Nation Security Council claimed that rebel forces, regrouping in the country after the Rwandan genocide, had taken control of the mines and were using coltan to fund their operations, often using forced or child labour.

These groups included the CNDP, a Tutsi rebel force led by General Laurent Nkunda, and the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a Hutu rebel group responsible for the Rwandan genocide of 1994, which had the backing of the Congolese government under President Mobutu.

The report concluded that the DRC was suffering a "systemic and systematic" looting of natural resources, with the CNDP alone raising $250m over 18 months by selling coltan.

After the report's release, some of the world's biggest mobile phone companies - Nokia, Samsung and Motorola - began monitoring suppliers with a view to eradicating Congolese coltan from their goods.

But a follow up report by the UN in December 2008 claimed the looting of the mineral in the DRC was still rife.

Rwanda is estimated to have made $19m from coltan sales in 2008, a rise of 72% on the previous year, even though no coltan is mined within Rwandan borders.

Experts say the production process, where coltan is cut with various other minerals and converted to tantalum, makes the final product almost impossible to source.

'Difficult problem'

However, protests over the trade in so called "conflict minerals" are growing.

Last month saw angry scenes outside the opening of the new Apple store in Washington DC by activists demanding the firm commits to a "clean" minerals policy.

But the firms boss Steve Jobs has said, despite Apple's best efforts, it remains "a very difficult problem".

Intel's Facebook page has also been hit by online campaign groups calling for tough international sanctions to control the trade.

Some of the worlds big hi-tech firms, fearing a consumer backlash, are now refusing to source supplies from anywhere in Central Africa, turning instead to Australia, Canada and Brazil.

Despite the growing international attention, no long-term policy has been introduced by the Congolese authorities to govern the extraction of coltan and manage industry revenues.

Although trials have been held, no proper certification scheme, akin to the Kimberly Process for diamonds, has yet been devised to identify and source coltan.

Unemployment

Sugar is set to become one of Africa's most important future exports, not only as a food product, but because of the part it plays in the production of the biofuel ethanol.

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the President of Brazil, the world's biggest sugar producer, has visited four African countries to advise on ethanol production and creating low-carbon economies.

Mozambique, still rebuilding itself after a 20 year civil war, is pinning its development hopes on sugar.

Although Mozambique's economy has grown by 8% a year in the last decade, more than half its workforce is unemployed. For those that are in work, 80% are farm labourers.

Sugar is a major African export

Mozambique's Centre for Promotion of Agriculture, Cepagri, hopes to benefit from rising sugar prices, which hit a 28-year high last year, by doubling production and increasing exports to five hundred thousand tonnes a year by 2012.

It has set aside 48,000 hectares for sugar production in six districts, with a view to creating 17,000 jobs.

The government has also invested $10m in a new sugar silo at the port in Maputo.

Some 40% of Mozambique's sugar exports go to Europe and the US.

The country has benefited from a preferential trading deal with the EU under the "Everything but Arms" initiative, despite opposition from Europe's powerful farming lobby.

'Good returns'

But anti-poverty groups are becoming increasingly alarmed about speculation in global food markets.

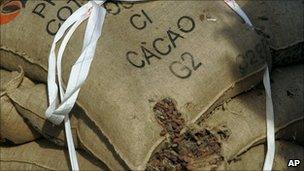

Armajaro Holdings, a Mayfair-based hedge fund, has just completed the biggest single purchase of cocoa beans in 14 years.

It has bought 240,380 tonnes of West African beans, equivalent to 7% of global supply, prompting fears that it intends to stockpile the goods, forcing up prices.

The price of cocoa has risen sharply in recent years

The boss of the fund, Anthony Ward, denies this claiming the investment is for the long term, saying: "If you're long, food will give you good returns."

But the World Development Movement wants this kind of trading to be curbed.

It's calling on the EU to cap the amount of money that private investors can pump into the market for so called "soft commodities".

The Fairtrade Foundation adds that deals like Armjaro's leave small farmers, who are unable to hedge against future losses, dangerously exposed to downturns in the market, and ultimately increase the risk of food shortages for Africa's poorest people.

But Mr Ward, the owner of a substantial vineyard at Voor-Paardeberg on the Western Cape, has indicated that he will continue his programme, targeting other African foodstuffs including sugar.

He is not alone.

One of the world's most powerful financiers, billionaire George Soros, is also understood to be buying food production capacity in Africa.