UK banking sector ready for payback

- Published

Banks are holding more cash but are still not lending more to customers

Like it or not, profitable banks are good for the UK.

Their fortunes are entwined with those of the wider economy - they facilitate growth, and their wellbeing depends upon it.

So when economies are healthy, banks do well; when economies are not, banks do badly.

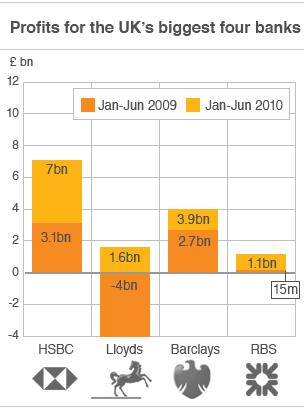

And the combined profits of £13.6bn for the first six months of the year reported last week by the UK's four biggest banks - HSBC, Lloyds Banking Group, Barclays and the Royal Bank of Scotland - suggest that they are recovering well.

On the face of it, this is quite some turnaround: In 2008 as a whole they lost £22.3bn, while in 2009 they made £13.7bn.

However, the reality is rather less clear than these headline figures would suggest, and the outlook for the banking sector remains somewhat mixed.

Trading out of trouble?

At first sight, the results would appear to show that the banks' investment divisions are in rude health.

At HSBC, more than half of total profits came from investment banking, while on paper at least, almost all the profit made by Barclays came from its investment arm - £3.4bn of £3.9bn.

But these figures are rather misleading, says Chris Skinner, banking analyst at the Financial Services Club.

"Investment banking is not driving profits. The banks hired people last year in expectation of an upturn in merger and acquisition activity that simply has not happened," he says.

In fact, he argues, the Barclays numbers don't quite add up, given that profits from bond and equity trading have actually fallen.

The explanation, he suspects, is that the banks' acquisition of Lehman Brothers in 2008 and the sale of its Barclays Global Investors Division last summer are still feeding through to the bottom line.

RBS' investment banking division also struggled to perform in what it called a "difficult" past few months.

So, we have to look elsewhere to find a reason for the banks' much-improved profits.

Bad loans turning good

But we don't have to look far.

All four banks saw so-called impairments suffered on bad loans fall dramatically.

This basically means that losses were not as bad as they had forecast, so they had to set aside far less money to cover them.

Indeed in some cases, the improvement in impairments contributed most of the profits made by the banks.

HSBC set aside £4.7bn compared with the £8.8bn it paid to cover bad loans a year earlier, providing a £4.1bn boost to profits - more than the entire profit figure for the first half of the year.

Lloyds saw an improvement of £6.9bn on a year ago, while Barclays received a £1.5bn lift. RBS saw a gain of less than £200m.

As the BBC's business editor Robert Peston says of Barclays: "If you strip out the fall in the charge for bad debts, it's difficult to see that, in underlying operational terms, there's much growth."

And this could be a problem if impairments start to rise again.

Mr Skinner believes there is every chance that they will. With governments cutting spending across the world, central banks removing stimulus measures and unemployment remaining stubbornly high, he believes banks may have to put more money aside in the coming months to cover bad loans.

Lending up, or down?

The banks will tell you that, despite the losses on bad loans, they are lending significant sums to businesses to help stimulate economic growth.

Indeed those that have received direct government support have been set specific gross lending targets.

Lloyds lent £5.7bn to small businesses in the first half of the year and £15bn in new mortgages, both ahead of government targets, it says. Combined, RBS lent £11.9bn.

And the banks that did not receive direct support have also done their bit, they say. Barclays lent £10bn to UK households and small businesses, while HSBC lent £6.5bn.

But many commentators are much more interested in net lending, which takes into account not just money loaned out, but money repaid as well.

And while net lending to small businesses rose very slightly at Barclays, it actually fell a little in the case of HSBC, Lloyds and RBS.

Small business groups have been particularly critical of the banks' lending record, arguing that they are withholding funds to build up capital reserves, while the new coalition government has promised further action to boost lending.

But the banks argue that there simply is not the appetite among businesses to take out new loans. Instead, they say, companies are looking to reduce debt levels.

As Lloyds boss Eric Daniels put it: "We can't prevent our customers from paying back. Our customers are behaving very prudently. Credit is available."

Indeed Lloyds says its loan approval rate during the first half of the year was 80%. The equivalent figure at Barclays was 85%.

The truth lies somewhere in between the two positions, but what is certain is that banks need to lend more if the UK economy is going to recover strongly. A lot more.

The bigger picture

For lending is absolutely crucial to the recovery. Companies need to invest to expand, which will help to drive economic growth. And they cannot invest without fresh capital.

The good news is that the banks are in a much better position to provide this funding. All four of the UK's biggest banks are now profitable and have made good progress in rebuilding their capital ratios following the financial crisis.

Indeed the recent European bank stress tests showed that UK banks are now the strongest in Europe.

And it's important to remember that it is in the banks' best interests to lend, for this is how they make most of their money.

The banks led us into recession, and now at least, they are in a position to help lead us out.

The one caveat, of course, is the government cuts, both at home and across Europe, that could derail the recovery and hit borrowers' ability to repay loans.

Taxpayer return?

There is some more good news.

UK taxpayers have invested more than £75bn directly into Lloyds Banking Group, RBS and Northern Rock (on top of the hundreds of billions of pounds of guarantees on bad loans), and there is a good chance that they will, at the very least, get their money back.

Taxpayers are already looking at a profit on their Lloyds shares

They should, in fact, make a profit, and a tidy one at that.

Northern Rock, which also reported a return to profit this week, still owes the taxpayer £22.5bn, but most analysts expect part of the bank to be sold to the private sector and the remaining loan book to be repaid over the coming years, with no net loss.

Meanwhile, the taxpayers' 41% shareholding in Lloyds has already become profitable, to the tune of £2.5bn, according to Mr Skinner.

He is also "absolutely confident" that the 84% stake in RBS that the government holds will also make a profit.

The only problem is, taxpayers will have to wait to see the gains from their investment.

Analysts say the government will not sell its stakes in the bank at least until its own comprehensive review of the banking sector is completed, which won't be for more than a year.

Mr Skinner thinks it will be longer than that.

"Taxpayers will get their money back, but the government will only sell its stake in the run-up to the next election [in order to gain as much political capital as possible]," he argues.

"Nine months before it will sell Northern Rock, six months before it will sell Lloyds, and three months before it will sell RBS".

Politics aside, bearing in mind the controversy surrounding the government bail-outs at the time, that sounds like a pretty satisfactory outcome for the taxpayer.