Taking stock of Nigeria market upheavals

- Published

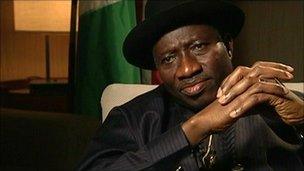

President Goodluck Jonathan has vowed to crack down on corruption

The removal of two of the most senior figures on the Nigerian Stock Exchange has sent a wave of alarm through Africa's financial community and among its many international investors.

It has again brought into question whether Nigeria is a safe place to do business.

Arunma Oteh, the new head of the market regulator, has warned that hundreds of employees could face criminal charges following an investigation into corruption and mismanagement.

Armed police have been greeting stockbrokers turning up for work at the Lagos exchange, to maintain order while inquiries continue.

The events on Africa's second-biggest stock market have their roots in the reform of the country's banking sector, under former President Olusegun Obasanjo in 2004.

Keen to revamp Nigeria's fragmented network of banks, the government introduced rules requiring each institution to hold at least 25bn naira ($166m) in capital.

The hope was that a handful of stronger, bigger banks would be better placed to service the economy, by lending to customers and raising cash through investment. After a string of mergers and acquisitions, the number quickly fell from 89 to 24.

Facing ruin

What followed next is still contested, but by 2008, some of Nigeria's banks had gone into meltdown.

Nine of the biggest - Afribank, Bank PHB, Equitorial Trust Bank, Finbank, Intercontinental Bank, Oceanic Bank, Spring Bank, Union Bank, Wema Bank - had to be rescued with a $4bn bailout, after a series of huge loans turned bad.

The new boss of the Nigerian Central Bank, Lamido Sanusi, sacked eight of the nine bank chief executives in a clearout that became known as the "Sanusi tsunami".

Arunmah Oteh says action is in the "best interests of the markets"

But the impact on the stock market, where banking shares made up more than half of all capital investment, has been huge.

The NSE has fallen 70% since its peak of trading three years ago and has seen $50bn wiped off its value. Many Nigerians face personal ruin as a result.

The Nigerian Securities and Exchange Commission is now investigating allegations that traders were ramping bank shares on credit lent from the institutions themselves.

When panic set in and the sell-off began, margins could not be covered, leaving a hard core of brokers sitting on losses estimated to be about $5bn. According to some analysts, up to two-thirds of brokers employed on the bourse are technically insolvent.

On 5 August, after the exchange's president, Aliko Dangote, and director general, Ndi Okereke-Onyiuke, were removed from office in an unprecedented step, Ms Oteh told a news conference that she had acted to restore confidence in the NSE.

"We decided it was in the best interests of the markets to take immediate and decisive action towards resolving these concerns," she said.

Mrs Okereke-Onyiuke, who had been director general for a decade, has vowed to appeal, telling a hearing at the Nigerian House of Representatives that the case against her was politically motivated.

The future for Mr Dangote, ranked on the Forbes list as one of Africa's richest men with a personal fortune of $8bn, is less clear. His representatives have refused to comment ahead of his evidence to a governmental hearing.

'Toothless bulldog'

Critics of the NSE say claim it has always suffered from poor oversight. The Nigerian Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) only came into being as recently as 1999.

Before that, the Lagos Stock Exchange Act, which was established in 1961 and later renamed the Nigerian Stock Exchange, acted as a self-regulating organisation.

Former President Obasanjo began reforms

Many feel that a laissez-faire culture has been allowed to persist, with the SEC regulator concentrating on the transactional side of the business, rather than policing the activities of traders and listed firms.

Bismark Ruwane, chief executive of Financial Derivatives, a Lagos-based consultancy, told the BBC: "We had a regulatory agency that over the years was accused of being a toothless bulldog, totally inactive and passive."

In April this year, a delegation from the US's own SEC visited Lagos to carry out its own inquiries. Its report has not been made public, but it is understood to contain details of serious malpractice at many levels on the NSE and a culture of "woefully inadequate" surveillance.

Arunma Oteh, a former vice-president of the African Development Bank and a Harvard Business School graduate, plans root-and-branch reform of the bourse.

She intends to enforce international accounting standards and require greater proof of solvency from brokers, who in turn will have to undergo more rigorous training to qualify for their licenses. Meanwhile, Emmanuel Ikhazoboh, former head of accountants Deloitte in West and Central Africa, has been appointed interim administrator.

Ms Oteh has announced plans for a new sovereign bond market to raise desperately needed cash for infrastructure projects, such as the building of the new national grid.

Nigeria is also creating a "bad bank" to mop up the $10bn worth of toxic debt that caused the crisis, though there is opposition from investors who stand to make big losses.

Image problems

But there are fears that the longer-term damage to Nigeria's reputation could be harder to repair.

Nigeria is Africa's most populous nation, home to 124 million people. It is also the world's eighth-largest oil exporter and, after South Africa, the biggest economy on the continent.

The US and Europe are trying to cultivate Nigeria as a potential ally in the war on terror. They also see a more developed and prosperous Nigeria as a bulwark against the conflict and disorder that reigns in many parts of West and Central Africa.

The new president, Goodluck Jonathan, came to power largely on an anti-corruption ticket, vowing to clean up the country's oil industry in particular.

Added to this, there is a new generation of young Nigerians, many of whom are returning home after years spent working and studying abroad.

This new middle class wants to create a better international image for Nigeria, weaning the country off of aid, and working towards a market-based economy.

Any signs that it is slipping back into its old ways could have serious consequences for these ambitions and even for Nigeria's standing in the world.

Because of an editing error an earlier version of this story had wrongly reported the names of the nine banks requiring a government bailout. The BBC can confirm that none of the banks originally named - Access Bank, Diamond Bank, GT Bank, Ecobank, UBA, First Bank, FCMB, Stanbic IBTC and Zenith Bank - was caught up in last year's bank bailout. The BBC regrets the mistake and apologises for any confusion we may have caused.