Bloodhound budgets: Indulgence or serious research?

- Published

Wing Commander Andy Green gives a tour of the Bloodhound SSC model

To break the world land speed record requires ambition, courage, persistence, ingenuity - and a great deal of money.

Raising the funds needed is one of the many challenges facing the British team behind the Bloodhound SSC (supersonic car) project.

The plan is deceptively simple: to take a car beyond the 1,000mph barrier, making it faster than a speeding bullet. Literally.

It may sound like the self-indulgent dream of an insatiable adrenaline junkie, but in fact the project has an altogether more altruistic purpose.

The idea, in a nutshell, is to inspire the engineering brains of the future and combat a serious decline in the number of engineering graduates in Britain.

"We're in trouble. Very big trouble," says Richard Noble, the director of the project.

"The fundamental problem is that the country is simply running out of engineers - and that's very bad news for the future of our economy."

Funding sources

The Bloodhound project could cost much more than current estimates suggest

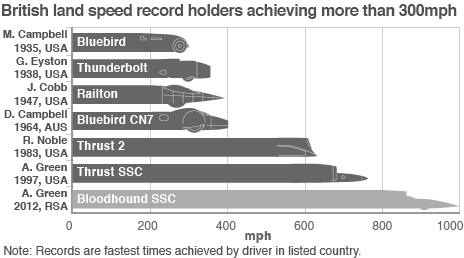

Mr Noble has form in the record-breaking business. He held the land speed record from 1983 to 1997. He then led the team behind Thrust SSC, the first car to break the sound barrier.

He says he was approached by Britain's Ministry of Defence and asked to come up with an "iconic" project that would inspire school children to become passionate about science and technology.

The result is Bloodhound.

But a project such as this has to be paid for. The process of researching, designing and building the car alone is expected to cost £6.6m - of which more than £4m still needs to be raised.

That could prove tricky, given the current mood of austerity and cost-cutting, with researchers across the land seeing the potential sources of funding shrinking fast.

Budget car

Meanwhile, there is every chance the Bloodhound costs will continue to rise, according to Mr Noble.

"The difficulty is that we are creating something that's never been done before," he says.

"We don't know how long it's all going to take once the car is up and running - or how much it's ultimately going to cost."

The budget for Bloodhound is already significantly higher than the £2.8m cost of Thrust SSC - the supersonic car that set the current world land speed record in 1997, when it achieved a speed of 763mph.

But given the scale of the technical challenges involved, the £6.6m figure is actually remarkably low.

By way of comparison, a top Formula One racing team can get through several hundred million pounds a year.

Prominent logos

Even so, attracting sponsors to such a high risk project has been far from easy.

The initial research was funded by just five founder sponsors, among them two universities and a government agency. The only corporate backers were the fuels company STP and the services firm Serco.

Since then, many more businesses have come on board. Most have simply provided goods and services, to help build the car and keep the project on track.

A select few, however, have also provided funding.

And it is this small group, along with the founder sponsors, that actually get to put their names or logos in prominent positions on the car.

'Risks worth taking'

But in a cloud of dust at 1,000mph, those logos are unlikely to be very visible. So will the sponsors really benefit?

"It's true our name won't be seen when the car's running," acknowledges Chris Boocock of Rainham Industrial Services, a company usually more involved in asbestos removal than record breaking.

"But this car will spend the rest of its life in a museum - and our logo will be on it. It's our bit of history - and that makes it good value".

So sponsors can expect to share in the glory if the project succeeds. Or in the embarrassment. After all, there remains a distinct possibility it could fail, and fail disastrously.

"Well, it's a bit like going to the moon or climbing Everest," says Chris Merrick, a director of the education supplies firm Promethean. "Faint heart ne'er won fair maiden, I guess."

Promethean, one of Bloodhound's most high profile backers, is supplying interactive tools to help schools and colleges keep track of the programme.

"There are risks of course," says Mr Merick.

"But we believe if we can help create a generation of scientists and engineers to solve the world's problems, then they're risks worth taking."

Small backers

Technological discoveries arising from the project will be shared

The backers who are already on board are clearly enthusiastic, but there's no doubt the project has struggled badly for funding - and has had a difficult time during the economic downturn.

Big household name sponsors are remarkably conspicuous by their absence, and during 2009 the project was nearly derailed when its bank refused to lend money to bridge a gap between sponsor payments.

So the team has been looking at new ways to fund itself - without relying wholly on the generosity of neither government nor big business.

It has just begun a quirky campaign to try to get small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) on board as well.

To achieve this, it has set aside a small amount of space on the car for up to 100 SMEs to put their names - each slot measuring 10cm by 10cm, and costing the advertiser £10,000.

In theory, this could raise up to £1m for the project.

No secrets

History suggests that the struggle to raise enough money will ultimately prove to be every bit as challenging as the land speed record attempt itself.

When Thrust SSC broke the sound barrier in 1997 it relied heavily on donations from the public, through its fan club, the internet, and a campaign by a national newspaper.

Without more support from the business community, the Bloodhound project may ultimately have to do something similar.

But there is one potentially lucrative source of revenue the project has rejected out of hand.

Although it will be developing pioneering technology, it will not be patenting or selling any of it.

"Absolutely not," says Mr Noble. "This is a project about education, about inspiring a new generation of engineers.

"That means we publish all the data freely so that people can look at it and understand how it works.

"You either do something like this properly, or you don't do it at all."

- Published31 August 2010

- Published19 July 2010