Irish deficit balloons after new bank bail-out

- Published

If Anglo Irish had failed, it would have done huge damage to the economy, the government said

The cost of bailing out the Republic of Ireland's stricken banks has risen to 45bn euros (£39bn), opening a huge hole in the Irish government's finances.

The increased cost will see the government run a budget deficit equivalent to 32% of GDP this year.

The cost includes a bill of up to 34bn euro to rescue the worst-hit lender, Anglo Irish Bank.

The government said it would now have to rewrite its budget to cut borrowing more quickly in the coming years.

But Irish finance minister Brian Lenihan defended the action, saying Anglo Irish Bank was too big to fail.

The Republic had previously committed to bringing its budget deficit down from 14.3% of GDP last year to 3% by 2014.

In a statement, Mr Lenihan said he still intended to meet that target, indicating huge fiscal tightening over the next four years.

'Huge damage'

Mr Lenihan defended the cost of the bail-out measures, which will cost the Republic's two million taxpayers the equivalent of 22,500 euros each.

"The bank had grown to half the size of our annual national wealth, so clearly the failure of a bank on that scale would do huge damage to the local economy here in Ireland," he said in an interview with the BBC.

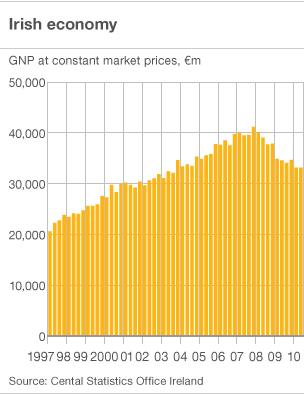

The Irish economy - once known as the Celtic Tiger - grew rapidly on the back of a property boom, fuelled by massive lending from the banks.

But when this collapsed, and lenders were unable to repay, the Irish banking system was plunged into crisis.

The cost of bailing out Anglo Irish could now cost between 29.3bn euros and 34bn euros in a worst-case "stress scenario", the government said.

That is up from the estimate of 22-25bn euro given last month.

The BBC's business editor, Robert Peston, said the equivalent of about a third of the Irish economy had gone into supporting the banks:

"If you added together all the capital provided to Ireland's banks by various arms of the state, taxpayer support to those banks in the form of capital injections is around 30% of GDP."

He said that would compare with around 6% of GDP in the UK for the equity injected into Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds and Northern Rock.

There will also be up to 7.2bn euros of additional support for Allied Irish Banks (AIB), which will in effect be nationalised.

Further help - of 2.7bn euros - will also be given to the Irish Nationwide Building Society.

Irish finance minister: 'There will be more pain ahead'

The Bank of Ireland was not deemed to need any extra support.

Despite the size of the numbers involved, the latest news on the bail-out was welcomed by some market analysts.

Padhraic Garvey, rate strategist at ING, said: "I think the market needs to know and here it is."

This reassurance was reflected in a slight fall in the Republic's cost of borrowing, which had hit record levels earlier in the week.

However, others doubted this would be the last such announcement.

"Alas I don't think we have final figures. We've had about four 'final figures' for Anglo [Irish]," said Brian Lucey, economics professor at Trinity College Dublin.

'Better health'

The Irish economy has faced one of the deepest recessions in the eurozone, with its economy shrinking by 10% in 2009.

The latest GDP figures showed it contracted by 1.2% for the second quarter. Greece's GDP dropped by 1.5% in the same period.

In an interview with the Financial Times, Mr Lenihan stressed that the country's financial health was better than other peripheral eurozone economies, saying it had borrowing already lined up to service debts and cover public services until the middle of 2011.

"We are not obliged to go to the markets. We are not under a clear and present constraint," he told the paper.

Mr Lenihan said the country would cancel its bond auctions in October and November and would not return to the bond markets until early in 2011.

The European Union's monetary commissioner, Olli Rehn, said he doubted that Ireland would need emergency aid from the fund established earlier this year by the EU and the International Monetary Fund to save Greece from bankruptcy.

There had been speculation that the Irish government would need such help - a suggestion rejected by the government.

- Published30 September 2010

- Published30 September 2010

- Published21 May 2012

- Published29 September 2010