Bleak outlook after Irish banks bail out

- Published

The troubled property market - depicted in this art installation - is at the heart of the Republic's economic woes

It may have been bright and sunny in Dublin this morning but that hasn't stopped people calling it Black Thursday.

It had been assumed that the independent Irish financial regulator and the governor of the Central Bank would disclose the expected final cost of Anglo-Irish Bank on Thursday evening once the markets closed.

So, people waking up this morning would have been at first surprised and then shocked, once they heard the figures.

Not that long ago a Trotskeyite academic was accused of being over the top when he said Ireland had moved from discussing state-controlled banks to a banks-controlled state.

For many people that comment now seems closer to reality than it did then.

Ireland's economic crisis is largely home-grown.

While property was important to the country's economic boom, the so-called Celtic Tiger, it was also central to the bust.

Nearly all the banks, but particularly Anglo-Irish, behaved recklessly lending money to property developers with little thought for their ability to pay it back.

The banks competed with each other for the developers' business.

House prices and the cost of office space rose dramatically with people queuing overnight outside some estates to get on the property market.

Inevitably, this led to further price rises.

And like all bubbles it eventually burst.

From the very beginning the Irish Finance Minister, Brian Lenihan, insisted that the debts of Anglo Irish Bank - the property developers' favourite bank - were large but "manageable".

That mantra was repeated every time it was revealed that the cost to the tax payers were larger than previously thought.

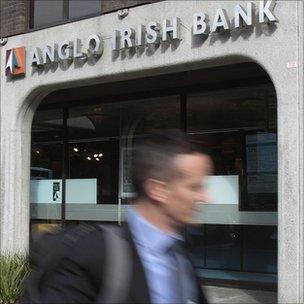

Anglo-Irish Bank, the worst affected but by no means the only troubled Irish bank or financial institution, is now nationalised.

It has long cast a shadow over Ireland's finances.

The cost of Irish borrowing has increased dramatically in recent weeks after the credit ratings agency, Standard and Poor's, predicted that the ultimate cost of Anglo would be 35bn euros.

'Worst case scenario 34bn euros'

At the time Official Ireland said those figures were extreme. But the numbers released today are not too different.

The government insists it can afford to bail out the banking sector

The Financial Regulator expects the final cost to the Irish tax payer over a 10 year period to be 29.3bn euros and in a very worst case scenario 34bn euros.

It does not end there.

The government also expects the taxpayer to contribute another 3bn euros to Allied Irish Bank (AIB) by the end of the year.

It owns the for-sale, First Trust Bank, in the UK.

And the Irish Nationwide building society needs another 2.7bn.

Throughout this crisis Irish people have been very stoic, accepting the need for cuts; there have been no violent Greek-style protests.

Only 1,500 people turned for a protest rally on Wednesday night but that does not mean people are not angry.

Mr Lenihan says people are very angry and rightly so.

Ireland is trying, in line with EU rules, to get its budget deficit down from around 14% this year to 3% by 2014.

But today's announcement is expected to increase temporarily the deficit figure to an incredible 32%.

'Tough budget'

The government insists that is a one-off statistic and that the underlying deficit figures are sound.

But one thing is now certain - the promised tough budget in November is now going to be a lot tougher.

People here are bracing themselves for new taxes and public spending cutbacks for several years to come.

In recent days there has been speculation about the possibility of Ireland having to follow the Greek example and accept EU and International Monetary Fund aid.

The authorities in Dublin and Brussels have down-played that likelihood saying the two countries are very different.

The Irish public have now endured two years of financial pain, becoming the poster boys and girls for government cutbacks.

But there is inevitably a question mark over how much pain any people should take for the recklessness of bankers.

Black Thursday is one thing, but a black decade is something entirely different.

- Published30 September 2010

- Published30 September 2010

- Published21 May 2012