What's the currency war about?

- Published

Which country will be left holding all the cards?

Over the past decade, the world has been divided into "deficit" countries and "surplus" countries.

Deficit countries, like the US and the UK, borrow from the rest of the world, so they can import more than they export.

Surplus countries, like China, Japan and many other Asian countries, do the opposite. They lend to other countries to help finance their exports.

The eurozone has typically imported about as much as it exported, staying in balance.

But within the eurozone there are also big imbalances: Germany runs a big surplus, while Spain, Greece and others run deficits.

Tension builds

During the financial crisis and global recession, imports by the deficit countries - and exports from the surplus countries - briefly collapsed.

But with the recovery, the latest trade data suggests that the old imbalances have begun to reassert themselves.

This has led to tensions. The US says it wants to export more, to help its economy recover. But the surplus countries don't want their exporters to lose their competitive advantage.

The quickest way to gain a competitive advantage is through a weaker currency.

And with the global recovery so weak, nearly all countries have been complaining that their currencies are too strong.

Unfastening the lynchpin

During the 2008 financial crisis, most currencies fell against the dollar. Investors bought the dollar, because they saw it as a safe haven.

But since then most currencies have slowly risen against the dollar again. US interest rates are near zero and the US is stuck in a weak recovery, making the dollar less attractive.

The Chinese pegged their currency to the dollar in 2007, and stuck with the peg throughout the crisis.

The People's Bank of China has bought up trillions of dollars in order to keep its currency weak against the dollar.

And the US is not happy, saying that it helps keep Chinese exports artificially cheap.

China's critics complain that the country runs a huge trade surplus, even though China is booming, while much of the world - notably the US - remains economically weak.

In June this year, Beijing finally agreed to loosen the peg - marginally - after months of US pressure. But the US says it is not enough.

The Chinese point out that - unlike many other exporting nations - they did not let the yuan fall against the dollar during the financial crisis.

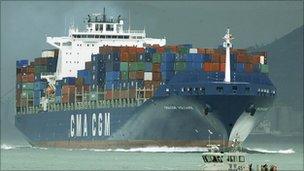

Despite weak growth in the US, Chinese exports just keep on arriving

Privately, the Chinese also worry that if they raise their currency too quickly, it could bankrupt many export companies and seriously destabilise their economy.

And China is not the only one to manipulate its currency. Korea and others have also intervened to keep their currency values down.

But the US sees China as a lynchpin - if it can get Beijing to strengthen its currency, it thinks other smaller exporters will follow.

Land of the rising yen

Meanwhile, spare a thought for the Japanese.

Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan was not altogether pleased by China's intervention

The yen has risen and risen since the 2008 crisis, hurting Japanese exporters and pushing the country back towards recession.

For years the yen used to be weak, because of Japan's zero interest rates made it a cheap currency for currency speculators to borrow in and sell.

But now the US, UK and Europe have near-zero interest rates as well, taking away the yen's advantage.

In September, the Japanese intervened to weaken their currency.

And the country exchanged angry words with Beijing after the Chinese suggested they might start buying up yen instead of dollars.

But the respite was short-lived, and since then it has strengthened even more against the dollar.

What can be done?

All this leaves one big question - what can countries like the US and UK do to reduce their deficits?

Mr Geithner is much more wary of threatening trade sanctions than many of his colleagues in Washington

One option is austerity. Consumers and companies are already cutting back on borrowing. If governments do the same, the entire country borrows less, and its deficit reduces.

The problem is that austerity in the deficit countries can lead to recession, especially if the surplus keep on lending.

Another option is looser money. But with interest rates at zero, central banks are left to resort to quantitative easing - printing money and using it to buy up debts, or intervening directly in currency markets.

But these are limited tool - as the Japanese have learned over the years.

Many in the US Congress hope that Washington will try another option - trade sanctions against China.

But that raises a spectre that is haunting the G20 meeting - the ghost of the 1930s, when protectionism started by the US led to a collapse of trade that was a big contributor to the Great Depression.

- Published7 October 2010

- Published22 October 2010

- Published21 June 2010

- Published16 October 2010

- Published8 October 2010