Gas and electricity prices: How are they calculated?

- Published

Gas prices are on the rise in December for some consumers

Energy prices are going up. Both British Gas and Scottish and Southern Energy (SSE) are putting up gas tariffs in December, and other major energy providers may follow suit soon.

The companies have blamed a 25% increase in wholesale costs this year. But have wholesale prices gone up? And how does the wholesale price relate to the figure that appears on your energy bill?

Is blaming the wholesale price justified?

Wholesale prices

With other costs to supply energy relatively fixed and constituting a small part of your overall energy bill, energy suppliers almost always cite wholesale prices as the reason behind a change in their tariffs.

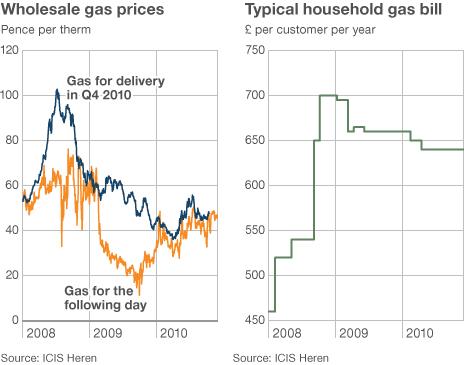

But at any one time there are many different wholesale prices, so to say they have gone up by 25% is meaningless. All of these wholesale prices have in fact gone up over the period quoted by SSE and British Gas.

But anyone who knows anything about the energy market also knows that a wholesale price movement can be found to support pretty much any retail energy price change - whether up, down, big or small.

So, how does the wholesale market work?

Before gas and electricity gets into your home, it is first sold to the energy suppliers.

In the UK, some of the big household suppliers produce or generate a proportion of their own energy. But they buy most of it either direct from the producers who generated the power or sourced the gas, and the rest is bought from the traded wholesale markets.

In either of these scenarios, the UK suppliers are usually paying the price set by the traded market, where a variety of producers, utilities and speculators are active every day.

Each energy supply company will have a small team of energy traders and analysts in their central office trading and monitoring price movements in the gas and electricity markets throughout each day. These energy traders are not dealing with a singular wholesale gas or electricity product - but a myriad of gas and electricity "contracts" which are defined by the period within which the energy is to be delivered.

So, as an energy trader, today I can buy energy for today. And that energy will be priced differently to gas or electricity which I buy for delivery tomorrow. Both of these prices will be different to energy priced for delivery this weekend, next week, next month, next year, or even in five years time.

Complications

To further complicate matters, contract prices can change every second, as sometimes hundreds of trades are made on the same contract each day. So the difference in price between contracts, and even for the same contract over the course of the day, leads to a plethora of wholesale prices.

Ben Essex says that buying energy on the wholesale markets is not simple

The traded price of a gas or electricity contract on the wholesale market will be defined by a number of factors.

In the near-term price changes are usually supply and demand-based. For instance, if it is colder next week, then the country will need more energy as households turn up central heating.

As a consequence the price of energy for delivery next week will probably go up. Longer-term prices, for example, energy for delivery in 2014, are more likely to change on broader macro-economic factors, as well as the prices of other energy commodities, primarily oil.

What do the suppliers pay?

Because there is not a single wholesale price, energy suppliers are over-simplifying the matter when they say their prices went up as wholesale prices have gone up by 25%.

In fact the gas and electricity flowing into households and businesses across the country today will have been bought by the energy suppliers anytime between now, and as far back as five years ago.

Suppliers will likely have spread out their purchases of energy for delivery today over a long period of time, to mitigate risk caused by volatility in the wholesale market.

Furthermore, each energy supply company will then buy and re-sell energy constantly in a bid to secure lower wholesale prices, further blurring the calculation of a wholesale price change.

This makes the 25% figure even more disingenuous. It also means that the company with the most effective trading strategy can end up paying much less for their supplies of gas and power than a competitor.

To give an example, if a supplier bought gas for delivery in the fourth quarter 2010, back in July 2008, it would have cost it over 100 pence per therm (p/th). Yet in spring this year, the same contract fell below 40p/th.

Competition

Since the liberalisation of the energy markets in the 1990s six major suppliers have emerged competing to supply us with gas and electricity. The "big six" - British Gas, E.ON Energy, EDF Energy, npower, Scottish and Southern Energy, ScottishPower - have successfully tied up 99% of the market share for both gas and electricity supply for the residential market.

With only six companies dominating the market, many people question whether competition exists. An allegation given credence each time the suppliers change tariffs en masse, even if the tariffs change by different amounts.

However, last year British energy regulator, Ofgem, investigated just this, gaining access to the suppliers' energy trading portfolios, and concluded there was competition in the residential energy supply market.

If there is competition, why do they change prices in unison?

From the suppliers' perspective, when they set residential energy tariffs, they have one thing in mind - profit maximisation. Tariffs need to be low enough to beat the competition, but high enough to keep their shareholders happy.

But when one supplier changes their tariff, it is as if they are revealing their hand in a game of cards. Other companies become emboldened to either increase prices or are forced to slash them to remain competitive.

So what can you do? From a consumer's perspective, the key factor which will promote competition and fair pricing in the energy market is if individuals respond to price changes, and switch suppliers frequently. The more customers respond to price signals, the more the suppliers will be forced to compete with each other.

The opinions expressed are those of the author and are not held by the BBC unless specifically stated. The material is for general information only and does not constitute investment, tax, legal or other form of advice. You should not rely on this information to make (or refrain from making) any decisions. Links to external sites are for information only and do not constitute endorsement. Always obtain independent, professional advice for your own particular situation.