M-Pesa: Kenya's mobile wallet revolution

- Published

Why has the developed world been so slow to adopt the mobile wallet?

Think of the developing world, and the first thing that springs to mind probably isn't cutting edge technology.

But since 2007, Kenya has been leading the way with an innovative mobile phone technology that has transformed the lives of millions of people and businesses.

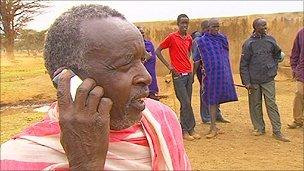

Using M-Pesa has meant Masai herdsmen no longer need to carry cash back from market

Mobile money transfer allows those without a bank account to transfer funds as quickly and easily as sending a text message.

The most successful of these systems, and the first to operate on a large scale, is M-Pesa, a joint venture between mobile phone giant Vodafone and Kenya's Safaricom. The M stands for mobile, and Pesa is Swahili for money.

Over 50% of the adult population use the service to send money to far-flung relatives, to pay for shopping, utility bills, or even a night on the tiles and taxi ride home.

Try to do this in London, New York or Paris and you'll find yourself with a very upset cab driver.

Coca Cola experimented with vending machines that let you pay by text message in Finland as early as 1997, however until recently mobile payments were largely limited to the online environment in the developed world. And they would normally require either a credit card, bank or PayPal account.

So can the developing world teach us a thing or two about the mobile wallet?

"The bank in my phone"

To use the service, customers first register with Safaricom at an M-Pesa outlet, usually a shop, chemist or petrol station. They can then load money onto their phone. The money is sent onto a third party by text message. The recipient takes the phone to their nearest vendor, where they can pick up the cash.

For business, the technology has revolutionised cashflow.

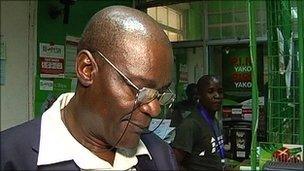

John Makusi Simiyu's Nairobi shop is the same bright green as the product it sells. His staff at this M-Pesa outlet are busy helping customers send and receive money.

The businessman also owns a transport and real estate company. M-Pesa has fundamentally changed the way it works.

He pays his crews, and transfers money to customers using the service. When one of his lorries breaks down, he no longer needs to go to the bank, and then travel miles by bus to reach the stricken vehicle.

"Today I don't need to do that. Just call me, tell me your problem and how much you need and I will text it through M-Pesa system."

"I don't need to go the bank when I have the bank in my phone"

One of the other great benefits is increased security. Mr Makusi says he no longer has to worry about being mugged while carrying cash.

John Makusi Simiyu no longer has to travel miles to pay for lorry repairs

"The work is done. Security-wise your money is intact, and you have your spare parts."

The success of the technology lies in necessity, according to Seema Desai, director of the Mobile Money for the Unbanked (MMU) programme. In the developed world between 96-98% of people have bank accounts.

"In rural Kenya it is completely different. My bank is hours away and I don't have internet access. But I do have access to a mobile phone.

"Even if you could get to a bank branch you'd need to prove your address with a utility bill. To be very practical about this not everybody in developing markets will pay utility bills, they may not even have a permanent address."

The MMU estimates over 80 similar services globally, with more in the wings.

"It's not just for customers at the end of the chain. We've seen businesses adopt mobile money to offer various business to business services, for example suppliers collecting payments from distributors via the mobile channel."

Helping money move

Nick Hughes and Susie Lonie are the people responsible for M-Pesa. The service has been so successful they recently picked up an Economist Innovation award. Ms Lonie says it's been a big hit with small traders.

Susie Lonie and Nick Hughes: "The product in Kenya now is so different to what we launched with."

"They were very quick to pick it up. For example people with market stalls paying for the produce to be delivered by M-Pesa rather than carrying cash. Carrying cash in emerging markets is a very risky thing to do."

"What it's done is increased the ease at which money can move around, not just individual consumers but small and medium-sized enterprises as well." says Mr Hughes

One of the big problems in the milk industry in Kenya has been how to get payment to the thousands of small one or two-cow milk producers, many of whom are women. A group of them got together and decided to create a payment system using M-Pesa.

"It's a really great example of how people out there in the market place who are struggling to move cash around, are saying we can use this tool to help us smooth our own business challenges."

Although not the first mobile money transfer system in the world - Smart and Globe were active on a smaller scale in the Philippines in 2002 - it is arguably the most successful, with over 13m customers. In March 2010 28.59bn Kenyan Shillings (KES) (£220m, $351m) was transferred using the service.

Originally funded in parts by a grant from the UK government, it was supposed to be a microfinance loan repayment system.

"After running the pilot for about nine months we started to see customer behaviour that said actually, this is much more useful as a person to person money transfer system," says Mr Hughes

"At that point the lights went on and we realised where the scale opportunity was."

The service has also been launched in Tanzania, Afghanistan and now South Africa, with trials underway in India.

Mobile wallet

So where does this leave the developed world?

Change is happening, although the ways in which we use the mobile wallet in the developed world differ significantly from services like M-Pesa, according to Howard Wilcox of Juniper Research.

Boku's James Patmore: "The mobile phone is ubiquitous"

"In the developed world mobile payments are made using slightly different technology, so typically we're looking at mobile payments on the web, payments for goods and services onto your bill, or we're looking at premium rate SMS payment."

Mobile payment online is fairly well-established, but what has really pushed the technology mainstream is the success of smart phones.

"We've seen the launch of PayPal's app enabling you to send money from person to person.

"Those sorts of payments are going to be more social payments, sharing the cost of a meal for example, or paying someone a small amount of money you might owe them that by bumping your iPhones together.

One company that does let you pay with your mobile is Boku.

They provide the mechanism to allow, for example, people to buy virtual money to use in games on social networking sites like Facebook. European managing director James Patmore says they are looking to capitalise on how easy it is to use a mobile phone as a payment mechanism.

"All the consumer needs to have is a mobile phone with either a pre-paid account or post-paid account, and the ability to remember their telephone number."

Users don't have to be registered to use the service, which takes payment from either pay as you go credit or your carrier, with a limit on how much you can spend each day.

The company operates in 65 countries, with customers typically spending less than $10 (£6.30) per transaction.

Don't touch

Near field communication (NFC), a contactless payment technology, is also changing the way we pay for goods in shops. In Japan and South Korea it's been in use for several years, having developed from smart card technology.

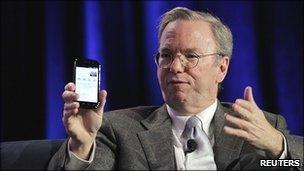

Verizon Wireless, AT&T, and T-Mobile plan to roll out a mobile payment NFC system called Isis by 2012, and Google's Eric Schmidt says his company's new phone will include an NFC chip. Mobile banking company Monitise is working on a pilot.

Google CEO Eric Schmidt with the Gingerbread smartphone, which will have NFC technology

In the UK, Barclaycard, which already offers contactless payment by credit card are in partnership with Orange to do the same for phones.

Overall, it seems the mobile phone becoming ever-more central to our finances, according to Juniper Research's Howard Wilcox.

"We're forecasting that nearly half of all mobile phones users worldwide will use mobile payments by 2014. This could be paying for a digital good like a music track, or it could be physical good which we're seeing increasingly."

So will we see M-Pesa vendors appearing on street corners from Madrid to Montreal? Susie Lonie thinks not.

"We're often asked, would we launch M-Pesa in Europe, and the answer is no, there is not the market need for it."

Orange is the latest entrant to the Kenyan market, and Safaricom has launched M-Kesho, a savings account, in partnership with Equity Bank. A variety of mobile financial services are on offer, and you can even pick up your money from an ATM.

Ms Lonie says "I guess ideally what we're looking for is to take cash out of the economy and replace it with electronic money".

The mobile wallet is here to stay.